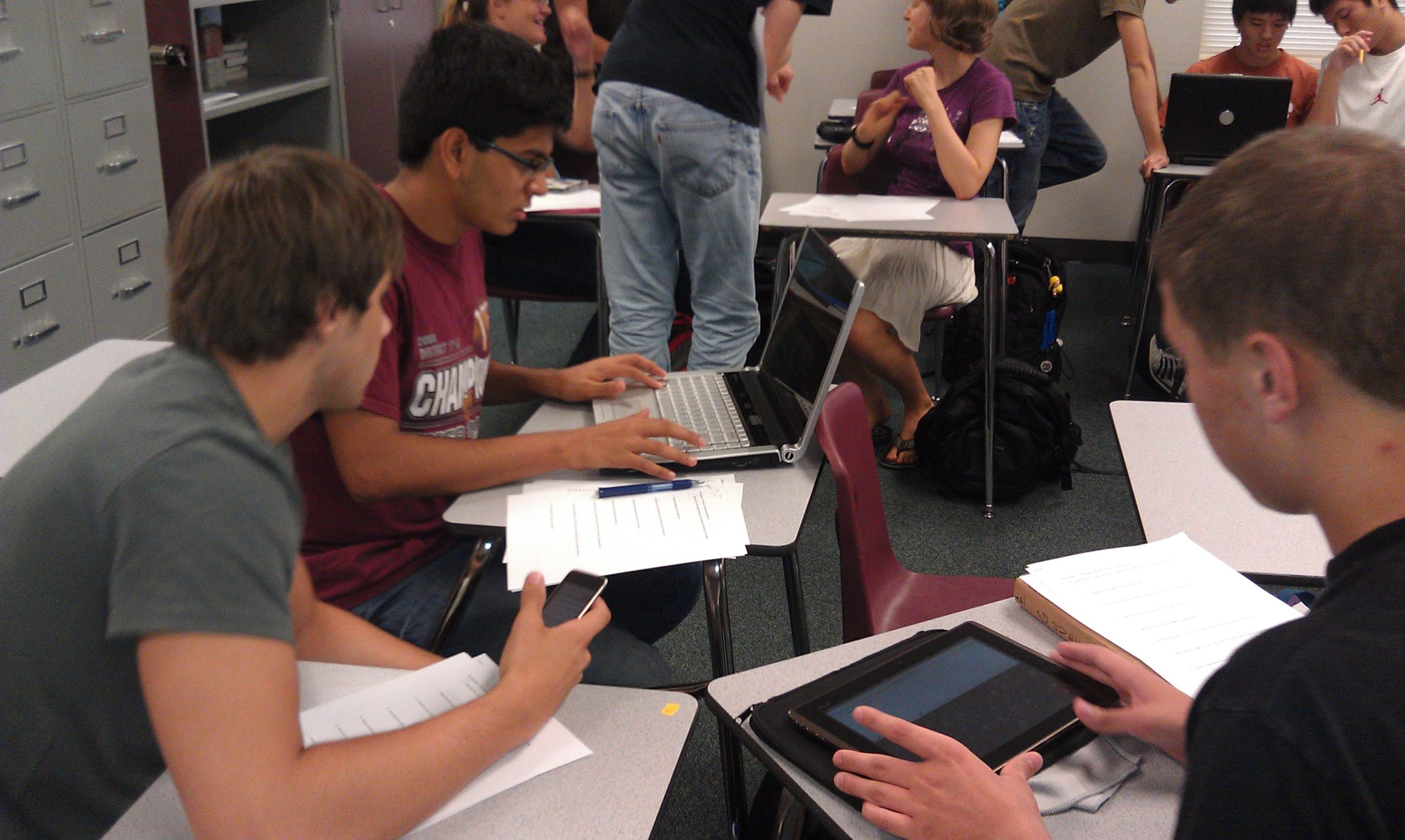

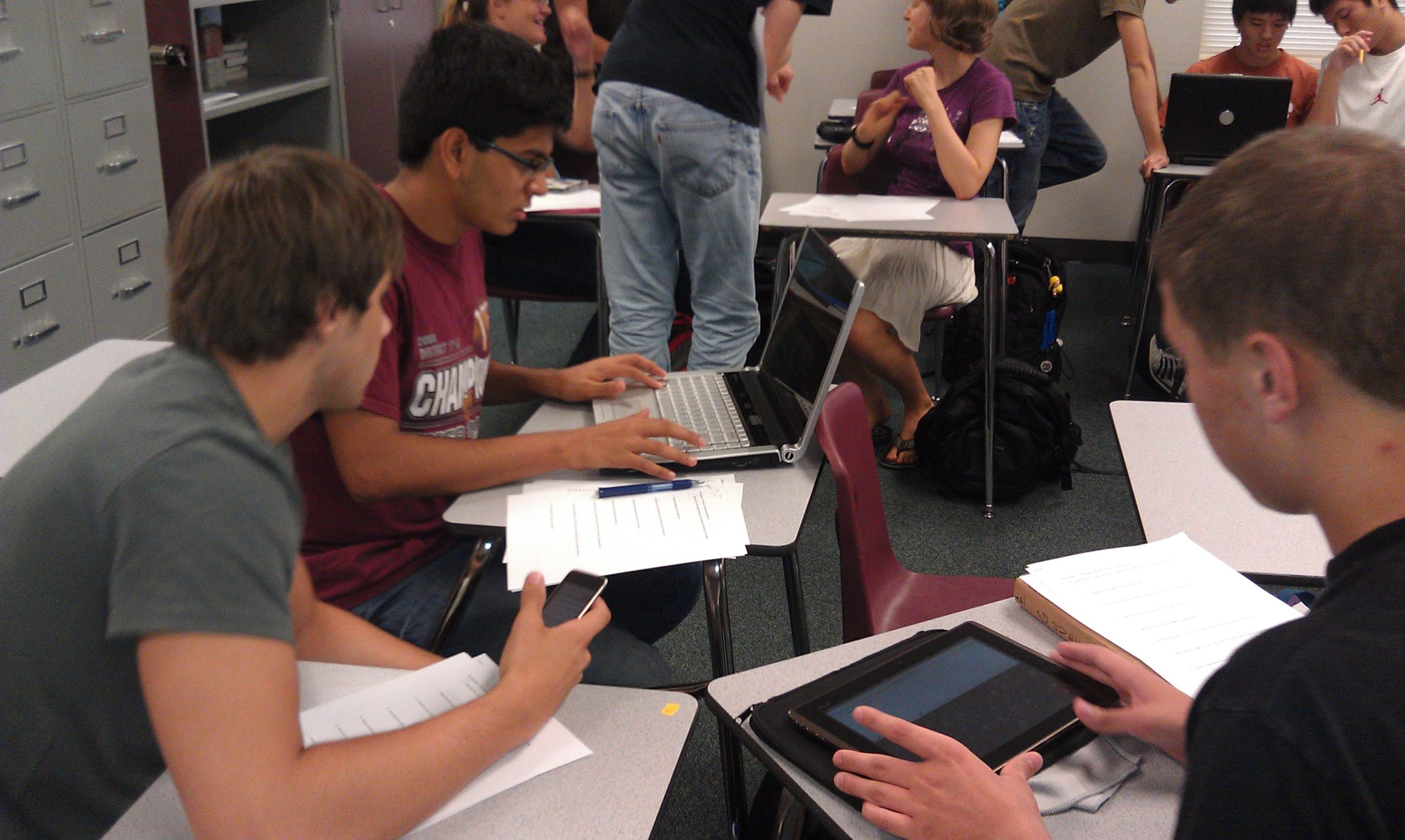

Walk through one of the high schools in the Katy Independent School District in Texas and you’ll see students staring at cell phones, headphones in their ears and fingers on their keypads. On every table in the lunchroom is a mobile or wireless device. Peek into a classroom and you’ll find students using laptops, tablets, and smartphones to research assignments. Last year, for the first time, all K-12 Katy students were allowed to bring their own devices to school, and the move was a predictable hit, says Lenny Schad, chief technology officer of the district.

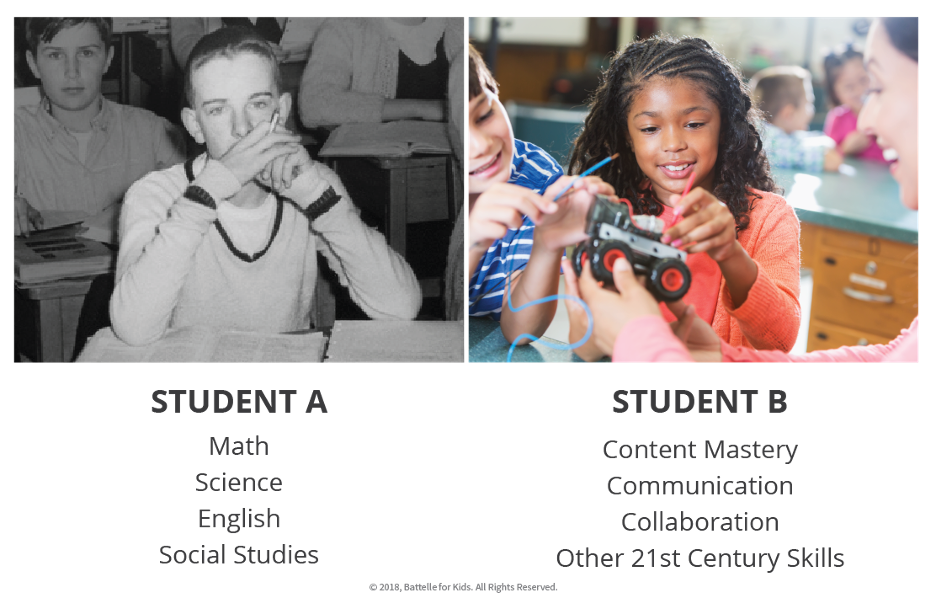

“We knew if we really wanted to reach the kids in a meaningful way, we needed to change instruction,” says Schad as he explains the district’s decision to introduce a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) program. Katy is one of many school districts that have turned to BYOD as an affordable way to ensure students have technology in the classroom. Although universities have long expected students to bring laptops and smartphones to campus, the devices have typically been banned in primary and secondary schools.

“[School] districts are rapidly shifting from worrying about cell phone use to more appropriately allowing them in the classroom,” says Chris Dede, Professor of Learning Technologies at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. As technology is integrated into classroom and homework assignments, students are better prepared for 24-7, real-world learning, he says.

“In the past seven or eight years institutions have spent so much time, money, and effort getting technology in the classroom—like electronic whiteboards and projectors,” says Julie Smith, vice president of K-12 education at CDW-G, which provides support services and technology to schools across the United States.“Now the students are demanding more…. They really want to use technology.” Just 39 percent of students say schools are meeting their technology expectations, even though 94 percent use technology at home to work on class assignments, a CDW-G report found in 2011.

But the benefits of BYOD come with huge challenges. Schools must ensure every student has equal access to devices both in school and at home. Twenty-three percent of teenagers don’t own a cell phone, and about 75 percent don’t own a smartphone, the Pew Research Center reported in March. Along with supplying extra devices, schools must improve their network infrastructure, boost tech support, and prepare students, teachers, and parents for a radical shift. Schools usually need three to five years to build up their infrastructure to fully support such a program, says CDW-G’s Smith.

“We’re always running out of bandwidth,” laments Jim Gerry, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Director at Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy (IMSA). The school had 20 mbps of bandwidth seven years ago and will have 250 mbps within two years.

“You don’t want to have to react to not having enough bandwidth—you have to proactively address it,” says Schad, who oversaw a major bandwidth increase in Katy. “If something goes wrong, it’s not just an inconvenience anymore. You’re impacting all learning in the district.”

As each student is likely to have on average about three devices, from a variety of providers, many teachers and administrators also worry about tech support. But some early adopters of BYOD have a simple solution: let students help each other.

At IMSA, where students live on campus, a student team has been providing tech support for 10 years. This group is essential for maintaining the school’s one-to-one program, says Mitchell Bieniek, a 2012 graduate who ran the Student Computer Support (CSC). “Our team of 30 students is able to put in the same amount of time as 3.5 full time IT workers,” he says. The team is available around the clock—even fielding 3 a.m. phone calls from frantic underclassmen—and some team members are certified to replace parts in products from certain brands.

IMSA’s student support plan could easily be imitated at a non-residential high school, says Gerry. “It engages the kids in a way that has nothing to do with academics,” he says. “It’s a chance to give students relevant, meaningful work that enhances their skills.”

Schad has found that students in Katy are already tech-savvy enough to fix basic problems. “Go into any classroom with a group of 20 kids and just ask ‘how do you do this?’ You have 20 tech support people helping you out immediately,” he says. That leaves IT employees to work on infrastructure issues—although Schad wishes he had done a better job preparing them for the challenges. “This new way of learning requires a whole new support model, and we were changing it as we were going down the road,” he says.

Inside the classroom, many fear that Facebook and text messaging will tempt students away from studying. But distraction and discipline issues can be avoided with quality professional development training, says Harvard’s Dede. “The problem isn’t the mobile devices, the problem is ineffective teaching,” he says. “There’s no point doing something like BYOD if the teachers haven’t been given professional development so they are using the devices in an interesting way.”

At Katy it took two years to prepare the community for the BYOD plan. But it was worth extensive preparation, says Schad. “The kids are picking the learning pathways they like,” he says. “It has become a really powerful learning environment.”

Schools Let Students Bring Their Own Devices, Then Struggle to Keep Up

Walk through one of the high schools in the Katy Independent School District in Texas and you’ll see students staring at cell phones, headphones in their ears and fingers on their keypads. On every table in the lunchroom is a mobile or wireless device. Peek into a classroom and you’ll find students using laptops, tablets, and smartphones to research assignments. Last year, for the first time, all K-12 Katy students were allowed to bring their own devices to school, and the move was a predictable hit, says Lenny Schad, chief technology officer of the district.