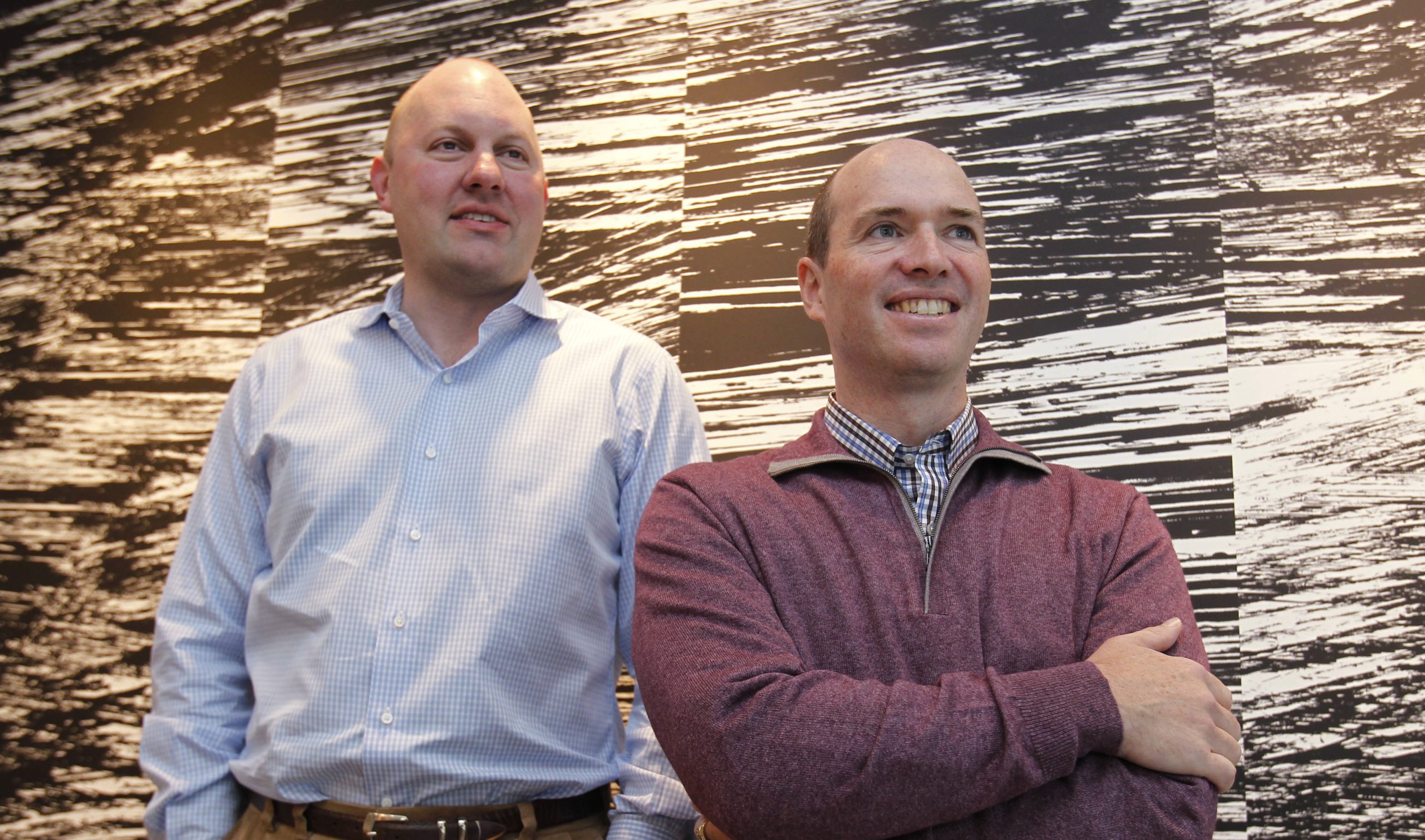

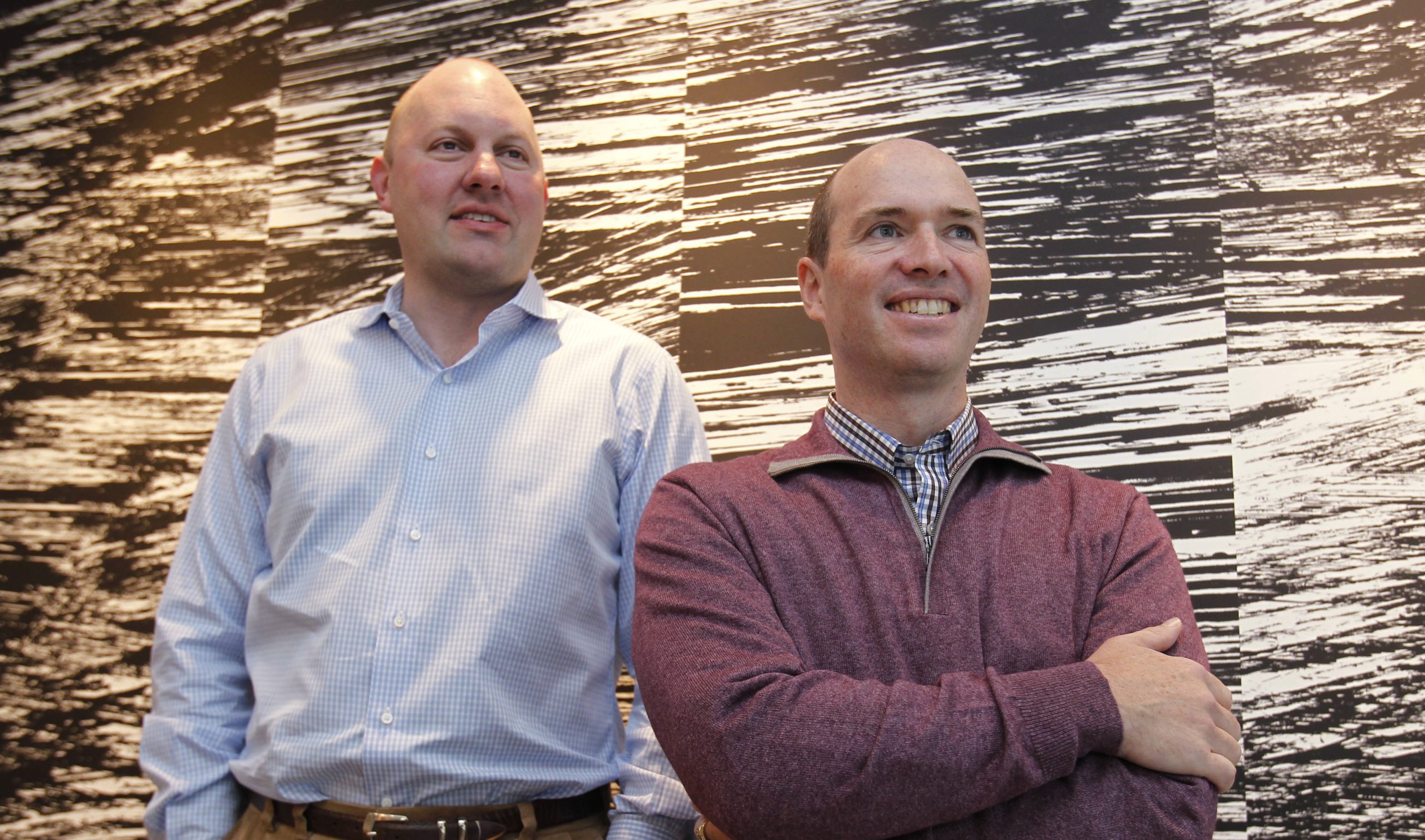

In the three short years since Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz set up shop as venture capitalists on Sand Hill Road, they’ve already established Andreessen Horowitz as one of the top VC firms in Silicon Valley, right up there with Accel, Benchmark, Greylock, Kleiner, and Sequoia. Some would argue that it is thetop firm. They’ve raised $2.7 billion across three funds and they somehow seem to get into every deal that matters. The Andreessen Horowitz portfolio includes such familiar names as Skype, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Foursquare, Pinterest, Airbnb, Fab, Groupon, and Zynga.

To say Andreessen Horowitz is shaking up the VC world is putting it mildly. “They are maniacs. They bully their way into every deal,” says a well-connected Google executive. A competing VC characterizes their arrival in the VC industry this way: “They are going around putting bombs in all the mailboxes on Sand Hill Road saying, ‘Fuck you, we are here.’”

Late last year, Andreessen Horowitz closed its third $1.5 billion megafund, and it took only three weeks to raise the money. Thanks to early bets on Skype, Zynga, Nicera, and Instagram, it’s already returned to investors twice the $300 million they put into its first fund. On Skype alone, Andreessen Horowitz made more than $100 million even though it only owned a small stake. Nevertheless, it played a key role in convincing Microsoft to buy Skype for $8.5 billion, three times more than Skype was worth only 18 months earlier when the company was spun off from eBay.

Early homeruns such as these gave the rookie firm an aura that suggested it could do no wrong. And institutional investors stung by a decade of mediocre venture returns were ready to buy the Andreessen Horowitz story. By the time it raised the most recent $1.5 billion fund, Andreessen Horowitz was able to command an almost-unprecedented 30 percent “carry,” according to one of Andreessen Horowitz’s limited partners. (The 30 percent is a maximum on a sliding scale). A venture fund’s “carry,” or “carried interest,” is the share of a fund’s profits the partners get to keep for themselves after they return the initial capital invested, and it is typically only 20 percent. A 30 percent carry is almost obscene. Or rather it would be if the six main partners at Andreessen Horowitz hadn’t recently pledged half of their future venture income to charity. For them, it is not about greed. It is about defying convention.

But the mere fact Andreessen Horowitz can find investors willing to go along with these terms speaks volumes about its leverage in the VC world. For instance, another rumored provision is that the firm’s carry is calculated “deal by deal,” according to a competing VC. What that means is that Andreessen Horowitz doesn’t have to wait to return its entire $1.5 billion fund before beginning to take its 30 percent cut of profits. If a single deal is profitable, the 30 percent carry goes into effect when that company has an exit—such as through an acquisition. Andreessen Horowitz won’t comment on the details of its financial arrangements with limited partners.

Other VCs view Andreessen Horowitz with a mixture of animosity and admiration. “The old VC industry still has antibodies against them, but maybe the old VC model is wrong,” says Mark Suster, a VC at GRP Partners.

Andreessen is a living icon in Silicon Valley, and he knows it. Netscape may be long gone, but it sparked the entire Web industry. Founders idolize him. After Netscape, Andreessen co-founded Loudcloud (later renamed Opsware) with Horowitz, who was an executive at Netscape. They ended up selling Opsware to HP for $1.6 billion in 2007. Both then became serious angel investors, and two years later graduated to venture capitalists with Andreessen Horowitz.

Andreessen himself currently sits on the boards of Facebook, eBay and Hewlett-Packard. Horowitz, who decorates his office with photographs of famous boxers, can also be a brawler. You don’t want to mess with either one of them. Most of the sources I spoke to for this story—even those who had positive comments—requested anonymity for fear of damaging existing business relationships with either Andreessen Horowitz (VCs all co-invest with each other and sit on boards together) or its growing portfolio of companies.

Why all the fear and loathing? The primary complaint about Andreessen Horowitz is that they are price insensitive when they decide to invest in a startup. “They are overpaying for deals,” says one VC, “forcing the Greylocks of the world to overpay as well.” In other words, it can drive up valuations even in the deals it doesn’t win. Another VC calls this proclivity to push up prices the “Andreessen Horowitz Effect.”

“I think it is sour grapes,” responded Horowitz when I first brought up the theory with him. “We rarely pay a premium,” he told me, calling the widespread belief among his competitors a “misperception.” Certainly, when it comes to venture capital, one investor’s premium valuation is another’s bargain. That is what makes it fun. The underlying thesis behind Andreessen Horowitz’s investing strategy is that in any given year only 15 companies will make up more than 90 percent of the returns. So it pays to get into those companies at almost any price.

The Andreessen Horowitz Effect

In the three short years since Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz set up shop as venture capitalists on Sand Hill Road, they’ve already established Andreessen Horowitz as one of the top VC firms in Silicon Valley, right up there with Accel, Benchmark, Greylock, Kleiner, and Sequoia. Some would argue that it is the top firm. They’ve raised $2.7 billion across three funds and they somehow seem to get into every deal that matters. The Andreessen Horowitz portfolio includes such marquee names as Skype, Instagram, Twitter, Foursquare, Pinterest, Airbnb, Fab, Groupon, and Zynga.