Corporate America has realized that diversity and inclusion—let alone equity—are lacking. We now see numerous firms and individuals adding inclusive or diversity leadership measures into the methods they use to assess, select, promote and develop leaders—typically known as competency models, capability frameworks or success factors usually made up of behaviorally defined characteristics of a person.

As experts in assessment, clients have asked us if we can add a “diversity management” competency or capability to their existing models. The answer is no. Nor should they take action this way. We can and do measure and develop inclusive and equitable leadership, but not by pasting on one extra capability. The reason? Effective leadership is inherently inclusive.

In other words, if you don’t have diversity, inclusion and equity embedded throughout your leadership assessment, you aren’t distinguishing the very best leaders.

We could assert the obvious reason why leadership must be inclusive: If you only hire certain subgroups regardless of ability, then you have inevitably overlooked capable people. If you do hire them, but then exclude them from opportunities, they may well depart for firms that better appreciate them.

Indeed, tacking on one inclusion competency can work against you. If you have, say, nine competencies and add one explicitly referring to inclusion, you’ve made it clear that it only requires perhaps 10 percent of a leader’s time and concentration. In the face of systemic or structural issues that often exist, it’s not appropriate or effective to say, “now it is inclusion time,” or “I have to think about inclusion for this one particular person.” Inclusion affects everyone, because everyone has experienced exclusion. Logically, leaders must have inclusivity built into the way they lead.

But why rely on unsatisfying assertions when we have proof of why inclusion matters?

The Proof

We at Ascent leverage 30 years of research into scaled leadership capabilities and competencies, resting in turn on nearly 20 years of the initial research into competencies as a concept. We have spent the past two decades intensively studying, assessing and developing executive leadership across numerous industries around the world.

The fruits of that labor are elegantly simple. We find that a mere six capabilities define the great majority of executive leadership. The devil, as always, lies in the details: We scale the behaviors from least to most sophisticated, so that we can accurately identify not just the presence or absence of a leadership capability, but the level required by a role or demonstrated by a person.

All of these behaviors come from actual executives, from positions across industries and geographies, and they predict the success of a person, their career path and their company. Looking at these, we see what better leaders actually do.

Example: The Leading Groups Capability

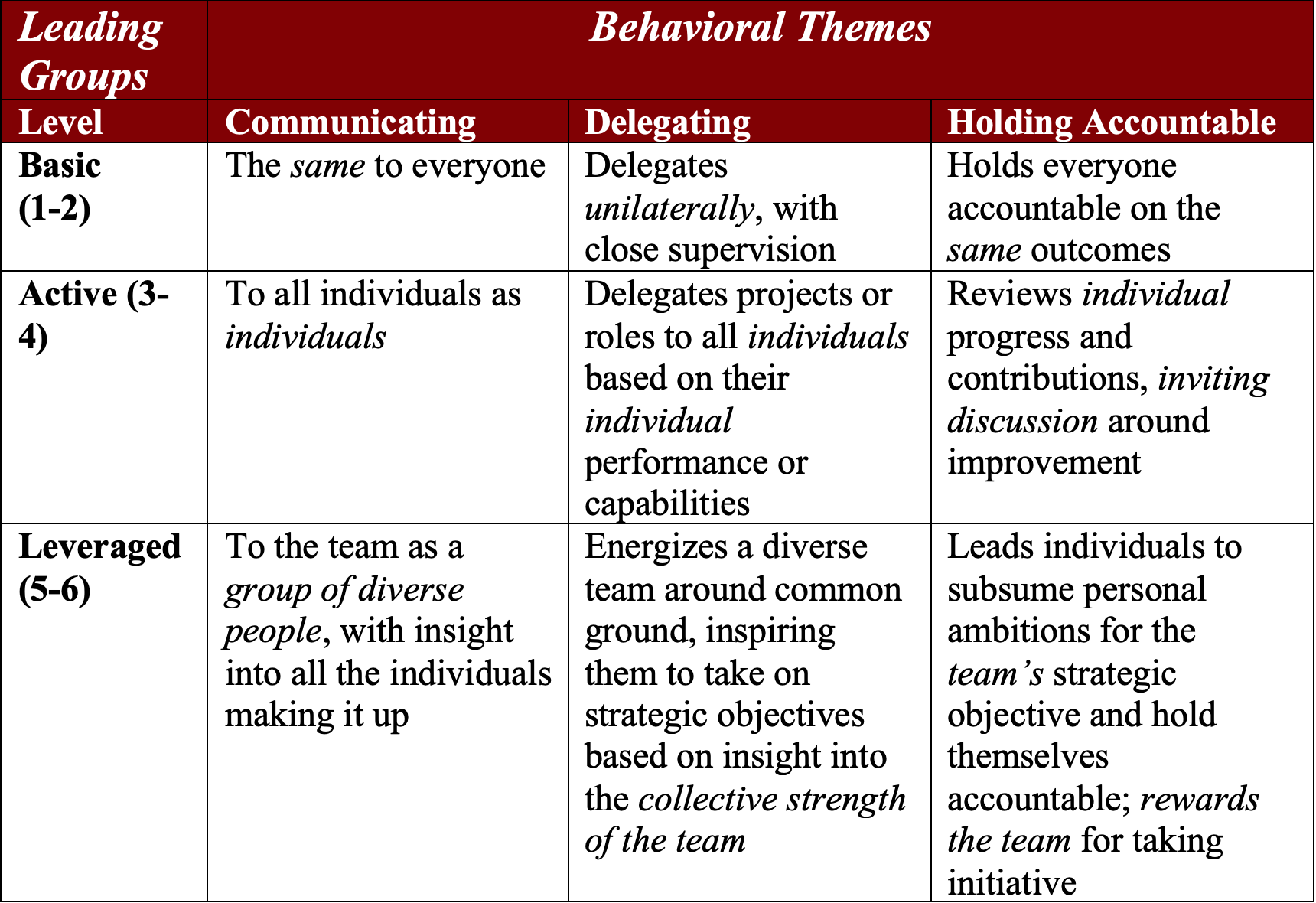

One of those six, which we call Leading Groups (but goes by many names), focuses on how one brings together individuals as a team, guiding and motivating them to act, delegating responsibility and holding them accountable for performance. Our research shows that to achieve higher levels, one must get better at inclusion for all individual members of a team.

For example, see this simplified excerpt of the first six levels of this scale, summarizing 30 behavioral indicators, all positive in nature.

A key factor we identified over and over again is that more sophisticated managers and leaders know their team. Going from basic to active is the difference between managing everyone the same way and managing each person as an individual.

Likewise, going from active to leveraged moves from the individual to the collective but is still anchored in the insight into each individual, so that the team can take advantage of everyone’s individual strength.

How Is This Inclusive?

Once you get to active levels—the most common levels we see among senior managers and executives—you can see the emphasis on knowing each person’s strengths in order to use it. But to land firmly on those levels, you cannot just manage one person individually—all individuals must be directly managed. Some may have great talent and can be left largely alone, but this is made explicit to the person rather than just abandoning them to their own devices. Others may need more support in terms of strategic understanding, principles or recommended practices. Skilled leaders provide what the person needs, which enables everyone to function at their best ability.

As you go up to leveraged levels, those we see among senior executives and top leaders, Leading Groups becomes even more inclusive, because it is about balancing an entire team by bringing together a known set of individual abilities, knowledge, skills, experience and potential to create a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts.

That’s what great leaders actually do; the more people they include, the greater the sum can be.

To see Ascent’s new Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Fellowship (and their other offerings), go here: https://ascent.net/fellowship/#fellowships-2021, or send a note to [email protected]

Stephen P. Kelner, Jr., PhD, is president of Ascent Leadership Networks.