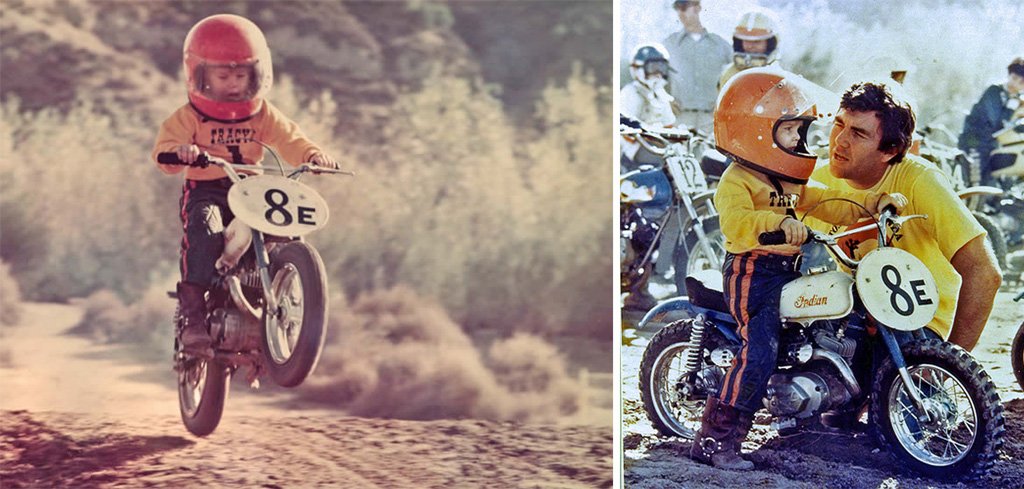

For a man who maintains that he is on the leading edge of a evolution, Mike McCoy looks pretty relaxed eating sushi at Pan-Asian Estaurant Lukshon, in the culver city section of Los Angeles. Lukshon is a regular lunch spot for McCoy, the CEO and creative director of a company called Bandito Brothers, which is headquartered just a few blocks away on La Cienega, and McCoy enthusiastically holds forth on an array of subjects—exercise routines, food, his cattle dog Einstein. But he’s most passionate when he discusses Bandito’s unorthodox place in the media world. “We’re a full-service media studio, a content-creation studio,” says McCoy, 45, who has been known as Mouse for so long that he doesn’t really answer to Mike anymore. (When he was a year old, his father gave him a gas-powered “peewee” motorcycle. “I was ripping around on it and looked like a little mouse,” McCoy explains.)

Bandito Brothers, which McCoy cofounded in 2006 with filmmaker friend Scott Waugh, makes movies, television shows and advertising, and also offers post-production services to the big Hollywood studios. But it combines those products with distinctly unconventional approaches to their financing, production and distribution. “We’re in the age of made media—content and advertising that audiences choose to watch and engage with—and we are the first made-media studio,” McCoy argues. “We’re not the only guys thinking about this, but we’ve executed.”

Early in the company’s life, for example, McCoy and his colleagues were testing new equipment for night filming, shooting McCoy racing his BMW M3 on LA streets. When Bandito posted the videos online, they got millions of hits—and numerous comments debating whether the film was “real” or not. The carmaker politely called to inquire what was going on, then hired Bandito to create more such videos.

McCoy loves creating work that goes viral; he talks a lot about the “maker movement” and the “disruption” of the old ways. As Warner Brothers executive Lance Sloane, who spent a couple of years working at Bandito Brothers, says of McCoy’s philosophy, “Disruption is not waiting for someone to hire you. Disruption is creating stuff without big media channels behind you financing it all.”

Case in point: the way McCoy made the 2012 thriller Act of Valor . The film, about Navy SEALs fighting terrorists, grew out of an ad campaign Bandito was shooting for the Navy. McCoy and Waugh decided that the material lent itself to something bigger, and spent the next three years shooting a movie that used active-duty SEALs as actors and incorporated SEAL training exercises and live ammunition into the action scenes; McCoy and Waugh filmed the scenes clad in body armor and camouflage. Shot for $12 million, Act of Valor—which McCoy calls the “anti-Hollywood war movie” because of its realism—would earn $80 million in theaters.

Bandito Brothers is a small company by Hollywood standards; current annual revenue is a notch above $25 million. But that’s partly by choice; McCoy and Waugh are more interested in doing things their way than in soliciting private equity to grow as fast as possible. To generate a steady revenue stream, Bandito and its sister company, Cantina Creative, do post-production work; the Hunger Games, Captain America and Iron Man movies were all polished by the studio. Bandito also crafts elaborate, unconventional ad campaigns with a viral emphasis for firms including BMW, Ford, Electronic Arts and Mattel. “Commercials have morphed into trans-media projects,” McCoy says. “It’s rare that a Bandito project is just a 30-second spot.”

“Trans-media” is a phrase that sounds like hollow jargon, but McCoy makes it real. In 2010, the toymaker Mattel and ad agency Mistress approached Bandito about reinvigorating the Hot Wheels brand; the image of the lucrative line of toy cars had grown stale. So the Mistress and Bandito teams came up with an idea for a Hot Wheels “Test Facility,” a secret, Area 51-like place in the Southwest desert where cars were designed and tested. Bandito created a series of short films inter viewing mysterious scientists and showing over-the-top stunts, like a car doing a backflip off a ramp before landing on another ramp. The longest of the films is about 22 minutes and features racing custom-built cars inspired by Hot Wheels models.

Shown online and on TV, the Hot Wheels Test Facility shorts were a hit—Mattel estimates that they have attracted more than four billion media impressions—but some online skeptics quickly snarked that the test facility didn’t actually exist. “So we said, ‘All right, how do you satisfy these people?’” McCoy recalls. In 2011 and 2012, at the Indy 500, the X Games and a track they built themselves, Bandito used Hot Wheels custom cars to stage three world records: the longest car jump, the longest corkscrew jump and the highest loop, that iconic swirl familiar to anyone who has played with Hot Wheels. “It was a home run for the brand,” McCoy says.

Taking risks has been a part of McCoy’s life since his childhood in canyon country , a small town in northwestern Los Angeles county. “My mom was a professional equestrian; my dad was a motorcycle racer, helicopter pilot and car racer,” he says. “Living a life of action and risk was just what we did.”

McCoy started racing motorbikes when he was only 4 years old and turned professional at 14. “I was making pretty good money at 14,” he says. “After 16, as you grow up, the money gets better.” But the racing life didn’t come without costs—frequent injuries. When he was 12, McCoy broke his leg riding; against doctor’s orders, McCoy’s father sawed off his son’s cast so Mouse could prepare for the next race. “My old man said the doctor didn’t really know what he was talking about,” McCoy recalls.

At 17, McCoy elected to skip college and became a professional stuntman; you can see his best work in Torque, a 2004 thriller about motorcycle gangs. But the 2000 Screen Actors Guild strike had left McCoy concerned about the uncertainty of a career in movies. So he used his own money to launch a digital media company called Sample Digital. “I was interested in technology,” McCoy recalls, and Sample did well; its clients included Disney, Sony, Paramount and Universal. “But I got bored, and wanted to return to a life of action.” So he merged Sample with another tech firm and started racing again. “I was drawn back to my natural habitat.”

McCoy is the kind of guy who likes to have many things in motion, and he soon realized that he wasn’t content simply to race. So he decided to make a film about his participation in the Baja 1000, the legendary—and extremely dangerous—off-road race across the Mexican desert. Typically, motorcycle entries in the 1,000-mile marathon, the longest such race in the world, will change riders after about 250 miles; riders tire at about that point, and fatigue can be lethal. But McCoy decided he would solo ride the entire race nonstop. “I said, ‘You know what? I’m in the best shape of my life,’” McCoy recalls. “‘Why don’t we make a movie out of all this?’”

The resulting film, 2005’s Dust to Glory, was “the start of Bandito,” McCoy says. Working with director Dana Brown, McCoy stationed 50 cameramen across the Baja Peninsula—“a lot of guys banding together like a brotherhood of filmmakers,” McCoy says. He finished sixth in the race but would have come in higher had he not crashed 80 miles before the finish line. “I was extremely tired and hit a huge ditch at about 75 miles an hour at night,” McCoy says. “I flipped across the desert and smashed my head pretty good. I broke my shoulder and my hand and my ribs.” McCoy picked up his motorcycle and finished the race with a time of 18 hours and two minutes.

But McCoy was undaunted. “I was 35 years old and had been completely sucked back into racing. I was pretty fearless at the time, and not in a great way,” he says. “To tell you the truth, I didn’t give a fuck.” Later that year, McCoy took a stunt job riding an ATV along a mountain range outside of Vancouver, Canada. At 70 miles an hour, McCoy lost control of the vehicle and went over the edge of a precipice. The 550-pound ATV landed on him. “My body was just destroyed,” he says now. Among other things, he suffered a double compound fracture of his legs. “I blew the bones in half and out of the skin,” McCoy says.

He would spend the next five months in bed—plenty of time for reflection. Over the years, he had broken every bone in his body except for his neck. I don’t want to be hurt anymore, he thought. It was time to pursue a different dream: becoming a film director and starting his own studio. “And when I got back up, I went full throttle into the creation of Bandito and applied that same sort of discipline and drive that I had in racing to this place.”

If you mention McCoy’s name to people in Hollywood, it’s his next chapter, making Act of Valor, that resonates the most, for its gonzo production history and commercial payoff. No one thought it would work. “We couldn’t finance it, we couldn’t get bonded for the movie,” says McCoy. “We were first-time directors. We had this crazy idea, and we had a handshake agreement with the U.S. Navy. Everyone sort of laughed at us.”

So he and Waugh put their own money into the project. “Everything we had in the world” went into shooting the first third of the film before the strength of the dailies attracted other investors. Relativity Media, an independent studio known for its aggressive marketing, bought the film to distribute. The $13 million deal, according to the website Deadline.com, was perhaps “the biggest money [ever] paid for a finished film with an unknown cast.”

Act of Valor is an action movie with sincere, patriotic themes of honor, sacrifice and duty. Critics didn’t love it, but soldiers, their families and their fans did. “SEALs are always played off as these Rambo-Terminator dudes, gung ho, overly macho,” says McCoy. But in making the movie, “I found some humble, down-to-earth guys who were really intelligent.” The three-year shoot, in which all the parts of SEALs were played by SEALs, created an unusually tight bond between cast and crew: “Your leads go to Afghanistan for nine months, and then you pick it up when they get home,” McCoy explains. “We became close friends.”

Commander Greg Geisen, who served as Bandito’s liaison to the SEALs, saw McCoy’s obsession become a reality. “Mouse has a passion for his projects that’s just boundless,” says Geisen. “There’s no such thing as working hours for him. He is intense and extremely creative.”

To shoot the film, McCoy and Waugh crafted a technical approach that, McCoy explains, “let us move in real time with the SEALs, as opposed to Hollywood, stopping and blocking every scene.” The technique allowed them to capture action that they would not be able to recreate—like when the Navy allowed him to film the USS Florida, a $4 billion nuclear submarine, surfacing for just a few seconds as the SEALs scrambled aboard along with a camera-toting McCoy, who was later digitally removed from the footage. “That was the mother of one-take shots,” he says now, still slightly amazed that it actually worked.

Since the SEALs couldn’t promote the film—their real names are not even listed in the credits—Relativity put McCoy and Waugh front and center. “We knew the movie was good and unique, but it was still a challenge since we didn’t have movie stars,” says Relativity president Tucker Tooley. “Scott and Mouse became our voices for the movie. They were eloquent and intelligent on behalf of the SEALs and the movie, and they became our stars.”

It helped that the two have been friends since childhood. “I know what Mouse is going to do and how he’s going to do it,” says Waugh, who filmed the submarine scene from a helicopter while McCoy was running on the sub’s deck. “It’s like working with a twin.”

The success of Act of Valor earned McCoy the offer that used to mean everything in Hollywood: the chance to direct big-budget studio pictures. “I passed on that direction across the board,” he says. “I’d rather do another $12 million movie that we control than get handed a $100 million movie.

The vibe at Bandito Brothers, which is controlled by McCoy and Waugh but has two minority-stake investors, is thoroughly California mellow. “Our creative usually starts out by the fire pit,” says McCoy. The company serves lunch for employees every day. “It’s just fantastic for morale.” Employee hours are staggered because of LA traffic, but also because the different businesses Bandito tackles attract different personality types. “The visual effects kids are night owls,” McCoy says. “If you come in here at nine at night, all the leftovers are being eaten by the kids.”

To keep perspective, McCoy lives in Montecito, far from the Hollywood scene, with his wife of seven years, Carmella McCoy. (Carmella, a photo stylist, and Mouse met on a shoot, and while she doesn’t have a formal role at Bandito, “she’s a huge artistic and creative force at the company,” he says.) “I need to be near nature and have dogs,” McCoy says. “A lot of my work is creative, conceptual, so it’s better to do it there. I have this cycle: creative up there, then come down here and deploy.”

The drive to Montecito can take up to four hours, so McCoy stays in an apartment above the Bandito offices during the week. He makes time for a daily two-hour trail run—and no time at all for the Hollywood party scene. “Mouse is good at uncoupling,” says Emile Gladstone, a former founding partner at the ICM talent agency who is now McCoy’s manager on some projects. “He goes to bed at 9:30 at night—it keeps him fresh. The athlete in him knows how important diet, exercise and sleep are.”

He has, after all, big plans. In Miami, he is developing a “race club” that he describes as “Monte Carlo Grand Prix meets Soho House meets Art Basel.” Also in the works is a “360-degree media and entertainment platform for Mattel” that McCoy refers to as “Hot Wheels for Real.”

There’s also a sequel to Act of Valor as well as a television series spin-off to occupy his time, but McCoy won’t get into that until there’s something tangible to discuss. “Being in development doesn’t mean anything in this town,” he says. “Everybody has a project. When we’re rolling, it’s for real.”

For more information on Bandito Brothers, contact managing director Jay Pollak at [email protected] or visit banditobrothers.com.