Auction house Christie’s started out on December 5, 1766, as a weeklong sale by founder James Christie of “household furniture, jewels, plates, fire-arms, china and a large quantity of Maderia [sic] and high flavour’d claret,” according to the original catalogue. “Christie was selling breakfast plates in his first lot,” says Jonathan Rendell, Christie’s deputy chairman. “Breakfast plates, booze and hay. We’ve come a long way.”

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the house, which in the centuries since its founding has become a style-setting behemoth—a bellwether by which to gauge the market for luxury commodities such as fine art, antiques, wine, cars and jewelry. “We reflect current taste, whatever that taste happens to be,” Rendell says.

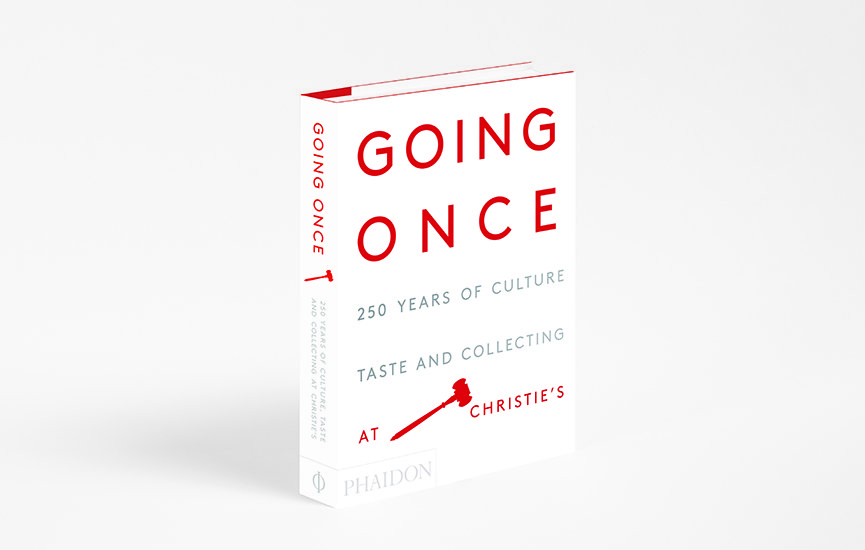

Christie’s recently released Going Once: 250 Years of Culture, Taste and Collecting at Christie’s (Phaidon, $60, 496 pages), which traces the auction house’s history through the stories of 250 lots. The commemorative book is a fascinating view into the evolving idea of luxury, as Rendell discussed with Worth.

Why are collections meaningful?

It’s someone’s biography in things. You really get to know the collector through what they collected. Collections also tell us when things are engaged in the marketplace. In the early 19th century, you have all these English portraits being produced that, by the early 20th century, are being bought by American billionaires to add prestige to their collections. But if you tried to sell some of these same English portraits now, nobody really cares. The portrait of a middle-aged man by a second-rate artist that would’ve been very desirable 100 years ago in the American marketplace, you couldn’t give away as a door prize today.

What were the criteria for selecting the lots featured in the book?

They needed to be significant objects that speak to the culture that produced them, but also the time in which they were sold and how they would be viewed in the world at that precise moment. Departments were asked to submit ideas that went before a committee. The entire firm worked on it, really.

Which objects didn’t make the final cut?

It’s really hard to try to keep yourself down to 250 objects. That would be unfair to the owners of those objects, wouldn’t it, if I were to start talking about why they weren’t significant enough?

Tell us, then, which ones stand out to you personally.

My problem is that I love everything. I’m a print specialist by training, but if you look at the book you’ll notice characters such as Madame Dubarry and Marilyn Monroe, who make the [object’s] provenance as important as the item itself. For example, the Marilyn “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” dress: It’s incredibly important in 20th-century American history. When you actually look at the object, it’s just a worn beaded dress. But throw in Marilyn Monroe, and it’s sort of wow. Same with Madame Dubarry, the mistress of Louis XV. She lost her head before we managed to sell the jewelry, but we got to sell the jewelry anyway—and it was one of the first big jewelry sales we had in the 18th century.

I was also heavily involved in the collection of Yves Saint-Laurent. So the Mondrian painting brings back to me spending months and months in the Saint-Laurent apartment showing clients through, marveling at the eye of these two guys. I mean, Pierre Bergé and Saint-Laurent had superb taste on every level in 10 different categories. And they weren’t trained art historians—they were people who just reacted from the gut.

Collectors get very passionate about amassing these objects. What drives that?

It depends on the collector. The true collector wants to build a conversation between objects. It’s important to them that the things they live with say something about them but also to each other. In a really great collection, you understand why things are sitting next to each other or in front of each other. What’s the train of thought?

And that’s not just with a fine art collection.

Not at all. I’m working on a collection right now where the emphasis is on objects, and everything [is inspired by] the imported carpet in the saloon; it informs the color and the style of everything else that’s in that room.

Would it be a mistake to just collect things that will appreciate in value?

Some people collect that way. Some people want significant objects that say something about them and their time. Some people want objects that speak to them, which is different.

A number of specialist departments at Christie’s have come and gone in 250 years. Which one has gained the most prominence that didn’t exist, say, a century ago?

Postwar Art. The idea of selling Modern paintings didn’t exist 100 years ago. You never really get Modern paintings coming to the fore until the Postwar period. But many people ask me when Christie’s began selling Contemporary Art. And for me the answer to that is 1766 because Christie was selling things by [Thomas] Gainsborough, who was his next-door neighbor. We’ve always been in the business of selling art.

Do you try to rediscover missed trends?

We strive along with the larger art community to bring things to light and make things that may have fallen into the shadows culturally significant again. In some cases that works, and in other cases it doesn’t. But we should be bringing a broad view of the art world to the marketplace.

What should novice collectors know when diving into the world of auctions?

You need learn to read a catalog properly, ask for a condition report and understand what makes an object culturally significant. And keep educating your eye. Decide on an area you’re interested in, then look at that in museums, auction rooms, galleries—understand why you’re attracted to these things. That could be as simple as an 18th-century Chinese tea bowl or an English porcelain cup. If that’s what turns you on, that’s what turns you on. But being educated in that world is what makes you a collector. christies.com