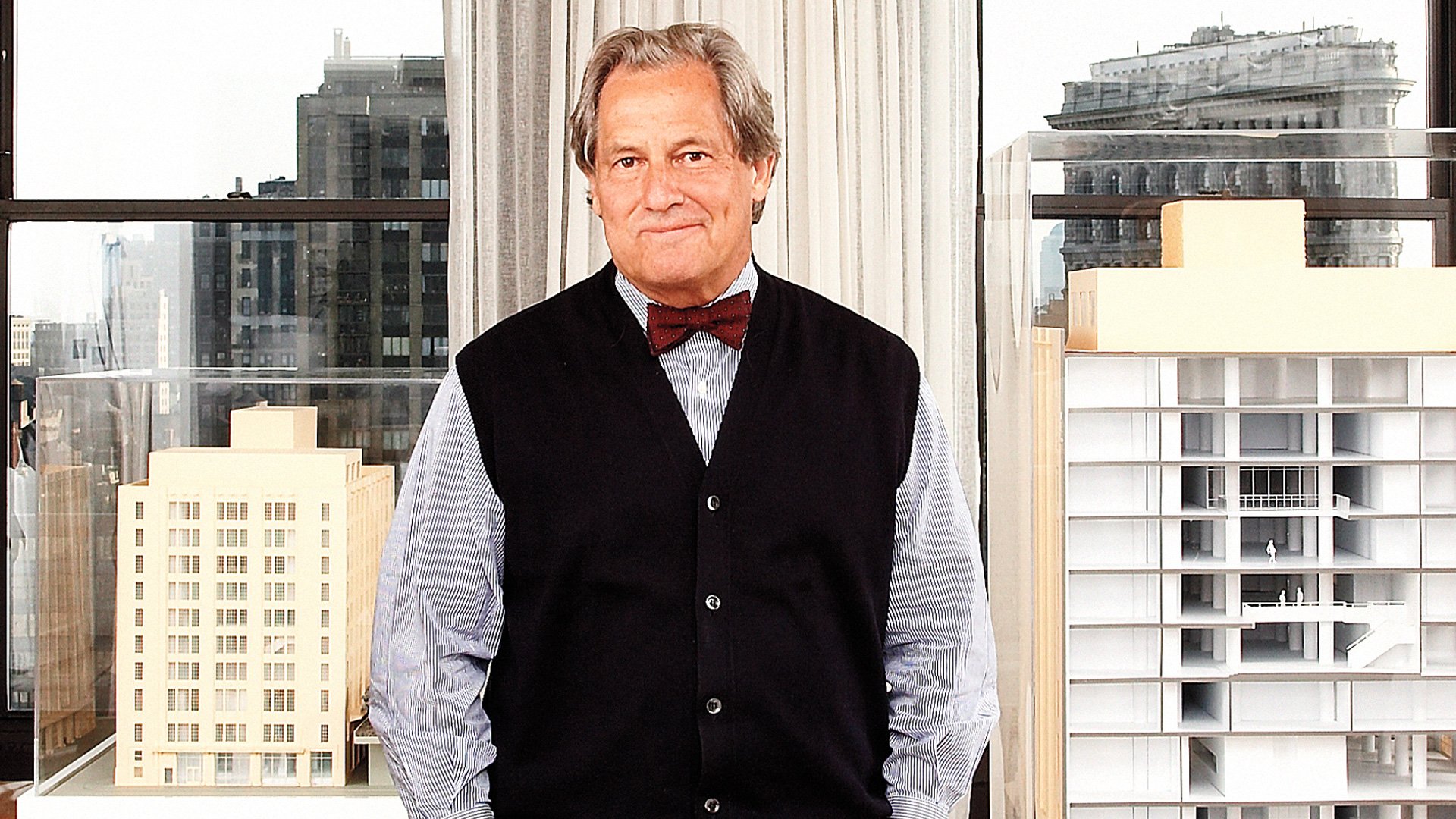

Dven while walking through a construction site, with saws grinding and jackhammers pounding, Chris Whittle, in his khakis and button-down shirt and bow tie, looks like a professor—a classics scholar at a small liberal arts college, perhaps. But as Whittle describes the transformation of this 215,000-square-foot building on 10th Avenue in Manhattan, he sounds more like a salesman. The former warehouse is now barren, stripped to bare walls and concrete floors. The floors are slightly sloped because, according to Whittle, the building was once a turkey slaughterhouse, and the slanted floors allowed turkey blood to drain into gutters. “But we’re not going to level them,” Whittle says. “We want to preserve the history!”

Starting in September 2012, this 10-story building will house Whittle’s newest big idea, a school for 1,600 children of the New York financial elite that Whittle has dubbed Avenues: The World School. Whittle wants Avenues to do two things: prepare students for a globalized world, and turn a hefty profit. The school will likely be the final venture in Whittle’s ambitious, lucrative, controversial and curious career, and the 64-year-old entrepreneur has a lot riding on it: an investment of $75 million from private equity firms, yes, but probably more important for Whittle, the possibility of a triumphant, redemptive final act.

If Whittle is feeling any heat, he shows no sign of it. He does admit to being busy—developing the curriculum, hiring faculty “right and left” and meeting with “hundreds and hundreds” of prospective parents. Unused to the idea of a for profit school, they’re cautious about sending their kids to an experiment, so Whittle needs to walk them through it. Right now, Whittle says, “Fifty percent of my time is with the parents.”

If Chris Whittle’s vision is realized, Avenues will be a striking new facility looking out over Manhattan’s High Line, the city’s newest, trendiest park. It will offer innovative classrooms— no tedious tic-tac-toes of chairs here, just small clusters of seats or seminar tables. It will have a great library, advanced computer facilities, expansive art and music studios, and 20,000 square feet of athletic space. In short, in the next 12 months Avenues will go from being nonexistent to being one of the best-equipped schools in the country. In theory, anyway.

Inside this state-of-the-art building, Avenues will preach a future-minded philosophy intended to prepare children for a world of diminishing borders. Starting in nursery school, Avenues students will be immersed in either Mandarin or Spanish. In the world of the near future, Whittle says, “an English-only child is not going to be able to compete.”

Students will also be required to take a “world course,” a study of international cultures and issues. And in time, the New York school will be the flagship of 20 or more Avenues schools located in “mega-cities” around the world—Mumbai, Beijing, São Paulo, London, Paris, Hong Kong, etc. Whittle plans to start opening two of those locations a year starting in 2014. If you’re a student at one Avenues school, you’ll be able to study at any of them.

New York City already has elite private schools, thank you very much: Dalton, Brearley, Collegiate, St. Bernard’s, Chapin and so on. Most of them are on the Upper East Side, they cost around $40,000 a year, and they generally offer a rigorous education, top-rate facilities and high acceptance rates at the finest colleges in the land. But there are not very many of these elite schools, and even for those unfazed by price, the competition for a cherished spot in one is brutal, an academic and social gauntlet that scars both children and parents.

There’s an opportunity here, no question. Avenues could appeal to parents who want the excellence those schools offer but dislike their social elitism; parents whose kids didn’t get into those schools; parents who moved to New York from another country and don’t know the social landscape well enough to play the private school game. Avenues could certainly appeal to downtown parents who don’t want to send their kids to the sniffy confines of the far-off Upper East Side.

At 60, Whittle recalls. “And I thought, ‘I have one last company in me,’ and started thinking about what that was.” The answer was easy.

But can Whittle deliver what he promises? Starting a school for 1,600 is a mammoth undertaking, and Whittle’s career is filled with grand visions that haven’t quite panned out.

He was born in 1947 in Etowah, Tenn., where his father was the local doctor. Even as a boy, he was an entrepreneur. Not an athlete, Whittle used to keep the stats for the local sports teams, then go home, write up the games for theChattanooga Times and Knoxville Sentinel and call in the copy. The next morning, he’d deliver the newspapers. “I was the first vertically integrated kid,” Whittle jokes.

Whittle went to the University of Tennessee, where he and fellow student Phillip Moffitt started a campus guide calledKnoxville in a Nutshell , which became a lot of campus guides, and then a company, 13-30, named for the demographic it sought to reach. In 1979, when Whittle was 31, 13-30 acquired Esquire for a reported $3.5 million; Whittle and Moffitt revitalized the moribund men’s mag and in 1986 Whittle bought out Moffitt and sold it to Hearst for $80 million. The two went their separate ways and 13-30 became Whittle Communications, a publisher of, among other things, controlled circulation magazines, called Special Reports , for doctor’s offices—content for a captive audience.

In 1989 Whittle launched Channel One, a company that donated televisions and VCRs to school classrooms on the condition that the schools show Channel One’s 12-minute daily broadcasts— and accompanying advertising.

Passionately denounced for bringing television and ads into America’s classrooms, Whittle was making schools an offer many couldn’t refuse: free technology in exchange for a mere 12 minutes. In 1994, he sold the company to buyout firm Kohlberg, Kravis & Roberts for a reported $250 million. It has since struggled.

Whittle now embarked on his most ambitious venture yet: After convincing Yale president Benno Schmidt to join him, Whittle launched Edison Schools, a for-profit company that aimed to start and/or manage 1,000 public schools. Hailed by advocates of school privatization, Edison Schools was a mixed success—very mixed. Hampered by opposition from many parents and teachers, Edison never came close to hitting that 1,000-school mark, and the quality of many of its schools was unimpressive. “We were not quite as consistent as we should have been,” Schmidt concedes now.

But in a deal whose bottom line was hard to figure, the Florida state pension fund bought the company for an estimated $180 million in 2003. It has since morphed into a semi-successful educational services company called EdisonLearning.

At 60, Chris Whittle was a wealthy man, but not a universally respected one. “I said to myself, ‘All right, I’m not going to be CEO of Edison,’” Whittle recalls. “And I thought, ‘I have one last company in me,’ and started thinking about what that was.” The answer was easy. “I just said, ‘Schools. That’s what I do.’”

Whittle convinced Schmidt, who is now 69, and Alan Greenberg, 60, a colleague from Esquire, to join him. The three have hired the previously retired principals of Exeter and Hotchkiss boarding schools—both in their 60s— to be the co-heads of Avenues. Other crucial positions have been filled by alumni of top jobs—all white men and women—at prestigious schools in Manhattan and elsewhere. Avenues may be the global school of the future, but the people working for it look a lot like the past.

If Avenues is to succeed—both on its own and, as Whittle hopes, as a revenue stream with which to repay investors and fund the development of Avenues overseas—it will have to turn a substantial profit. How will one school do that? I put that question to Alan Greenberg, who spoke about what it really costs to educate a child. The best public school systems, he said, spend maybe $20,000 per kid. But their students get test scores comparable to students in New York’s top private schools. Avenues, he implied, could educate a kid for $20,000 while charging twice that.

Where will the cost savings come from? Greenberg gave one example. “There are schools in town that teach 15 languages,” he said. “We teach two. Huge efficiency. You don’t have a classroom with three kids taking Russian.” That, he added, was a small point. “It’s decision after decision after decision like that.”

Some parents may be put off by such calculations, but such is the demand for good schools in New York that many may happily live with them. After running full-page ads in the Times and The Wall Street Journal , and hosting events for parents at chi-chi locales such as the Crosby Street Hotel, the Soho House and the Standard—watering holes better known for the destruction of brain cells than their development—Whittle says that Avenues has received over 1,200 applications for the fall of 2012.

For Whittle, it’s another chance to show that he’s not just in it for the money. “I’m not about public schools or private schools,” he says. “I’m about better schools.”