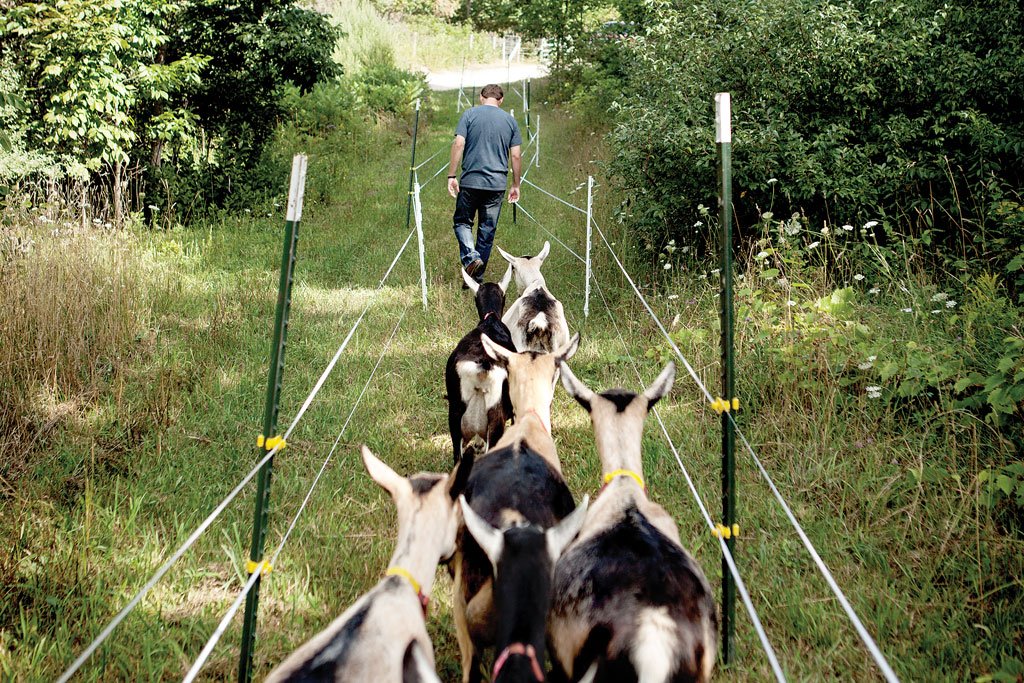

A few weeks ago, the hedge fund manager Mark Spitznagel was walking through a wooded area on his 200-acre farm in Northport, Mich., shouting at goats. “À droite! À droite!” he called, urging the animals to return to a path from which they had strayed in order to nibble on the surrounding brush. When Spitznagel was first launching his goat farm and creamery, called Idyll Farms, in 2012, he hired consultants from France—but of course—to come to Michigan and help train him and his staff, and the goats have grown used to hearing commands in French. “À droite! À droite!” Spitznagel shouted, tapping on the ground with a long, hooked walking stick he sometimes uses to herd the animals.

Dressed in jeans, an Idyll Farms T-shirt and a baseball cap, Spitznagel didn’t exactly look like he’d ambled in from the Provence countryside. But the goats, about 40 friendly, curious animals, lifted up their heads, and seeing that Spitznagel had progressed down the path, began trotting after him, falling into a caravan about two or three goats wide. They seem intelligent, I said to Spitznagel. “They’re herd animals,” he responded. “They’re as smart as any investment manager out there.”

Last summer, Spitznagel transported 20 goats to Brightmoor, a Detroit neighborhood replete with abandoned homes and overgrown lots. He hoped to create an “urban farming experiment” in which the goats would serve as landscapers and Spitznagel would hire and train locals as goatherders. Similar programs exist in several cities across the country, but Detroit politicians were not happy—Spitznagel had not asked their permission because he’d been told they would reflexively say no—and the goats had to go. “It was kind of a kick in the ass, but I don’t regret doing it,” he says.

Mark Spitznagel is an unusual man. At 43, he has amassed vast wealth (he won’t say how much) by pursuing an investing strategy that much of the financial world considers, frankly, a little nuts. Through his hedge fund, Universa Investments, Spitznagel buys puts and options that lose small amounts of money if the stock market is either flat or up. If the market goes down, however, Spitznagel can make enormous sums. The deeper the drop, the greater his return. Investors in Universa can expect to lose money for years on end—but if a crash happens, a black swan event, for example, or what Spitznagel considers more likely, the implosion of government interventions that have propped up the market, Universa investors can make many, many multiples of their equity. In 2008, when the S&P 500 plummeted 37 percent, Universa was up 120 percent.

A New York Times reporter dubbed Spitznagel a “fearmonger”; others call him a “doomsday investor.” “Every time you turn on the news and the stock market has taken another hit and the federal debt ceiling is on the verge of caving in, Mark just made another million,” Spitznagel’s brother, Eric, an editor for Men’s Health magazine, wrote in a Times essay about the challenge of having an immensely wealthy sibling.

That’s basically right, but it’s reductive. Spitznagel’s investing strategy is an extension of his deeply held libertarian beliefs about government intervention in the marketplace. For profiting off market crashes, “I’m always in this position where I look like the jerk,” Spitznagel says. “The jerks should be Ben Bernanke and Alan Greenspan” because of Federal Reserve moves that created stock market and housing bubbles, and for the ways in which the Fed intervened to ameliorate the consequences of those bubbles. “There are banks that are alive today that have no right to be,” Spitznagel says. But when the consequences of those interventionist, market-distorting policies do kick in, Universa is there to pick up the pieces.

Yet Spitznagel is unusual not just because of how he invests, but how he lives—far from the typical hedge fund milieu of Wall Street and Greenwich. He bought Idyll Farms in 2012 because, as the 40-something father of two young children, he wanted to feel engaged with something real, something tangible, and he wanted his kids to have that connection too. Spitznagel expects that his son, Teddy, now 8, will work in the hay fields, his 6-year-old daughter, Silja, will be in charge of milking, and both of them will walk the goats along the same trail we’re on now. Amy, Mark’s wife, works on the marketing and distribution of the cheese.

Spitznagel wants to show that you can create a sustainable, profitable business without the help of government subsidies or growth hormones or artificial fertilizers or other staples of modern factory farms—the agricultural equivalent of quantitative easing, as far as he is concerned.

“I want to demonstrate that we can make this world-class product in an ecologically sustainable way that’s also economically sustainable,” he explains. “I need to be able to show that.”

When Mark Spitznagel was a boy, he spent five years of his childhood in Northport. His father, Lynn Edward Spitz-Nagel (Mark dropped the hyphen) had moved the family there so he could serve as minister of a small United Church of Christ congregation. The UCC is a liberal Protestant denomination, and this was the ‘70s; Spitznagel senior was a civil rights advocate and antiwar activist. Mark’s mother, whose name is also Lynn, cared for Mark and Eric and began to make sculptures using natural fibers such as dog and goat hair.

“I grew up to be free to be you and me,” Spitznagel recalls. “Cat Stevens was the soundtrack of my childhood. One morning I opened my bedroom door and found a stack of books by Gandhi that my father had left for me to read.” Mark, however, was a budding capitalist. Starting in the second grade, he monopolized local paper routes. “I basically had all the routes in the area, hired my classmates and paid them a wage,” he says. “I had a mouth like a drunken sailor, and I used it a lot on my staff. I remember always being flush—kids came to me for loans. So I recognized that it was good to have a lot of money.”

By high school, he described himself as a libertarian; he subscribed to National Review and attended talks by Ron Paul, then a Texas congressman and perhaps the country’s highest-profile libertarian. “There could have been some rebellion going on,” Spitznagel admits. His philosophy: “The government shouldn’t intervene in our private lives and things like our money.” Mark “ruined many family dinners with his Reaganite free-market propaganda rants,” Eric Spitznagel would recall.

Spitznagel loved Northport—bordering Lake Michigan, it has a small-town aura that hasn’t changed much in the decades since he first lived there. But around the time he was in fifth grade, his father moved the family to the Chicago suburb of Matteson, where Lynn Edward became minister of a larger church. Mark was not a fan of suburban conformity. “We lived on 213th Street,” he recalls. “Imagine that—213 streets, all of which are identical.”

He took up the French horn, throwing himself into study of the instrument with what was by then his typical intensity. “By sophomore year, I was probably the best high school player in the country; I wanted to be the principal horn player of the New York Philharmonic or the Chicago Symphony.” He was accepted into the prestigious Juilliard School of Music in New York. But when Spitznagel woke up in the morning and started practicing the horn for hours, or took the bus into Chicago on weekends to take lessons or go to auditions, it wasn’t out of sheer love for the instrument. “I wanted to get better because I wanted to beat people,” he says.

Such confessions can make Spitznagel sound like, as he puts it, a jerk. He isn’t. You wouldn’t call Spitznagel warm and fuzzy; he’s not the kind of guy who’ll greet you with a bear hug and a slap on the back. But he’s funny in a dry, understated way, thoughtful and candid. Asked a question, he’s more interested in delivering a genuine answer than one intended to reflect well upon him. He can have an edge that sometimes shows itself. When I sheepishly admitted to Spitznagel that I dislike goat cheese, he said, “I know some 5-year-olds who feel the same way.” He would make a lousy politician.

He might have made a great musician, but when he was a high school sophomore, his course changed dramatically. One member of his father’s congregation was a man named Everett Klipp, a long-serving member of the Chicago Board of Trade. Lynn Edward took Mark to see Klipp in action at the CBOT, and Spitznagel instantly found a new passion: futures trading. He loved the furious energy of the pit, the way the traders would collectively surge and subside and surge again, like a crescendo in a Mahler symphony or a flock of birds, rising and falling over the water. The French horn quickly faded away; Spitznagel became a Klipp devotee. “I knew, when I was in high school, that I was going to be a great trader—I worked my ass off to get there. I was carrying around agriculture reports, listening to farm reports on the radio.” Over his bed he posted a chart of corn prices.

Though his father no longer required him to attend church on Sunday, Mark would go just to get a few words in with his new hero. Klipp would take him on as a clerk during his summers off from Kalamazoo College—where Spitznagel had earned a music scholarship, which he quickly lost because he stopped showing up for orchestra rehearsal—and when Spitznagel graduated, he joined the Board of Trade at age 22, “the youngest trader in the bond pit,” Spitznagel recalls. He paid for his $480,000 membership on the board by writing a program for the Hewlett-Packard “financial calculators” then in use; it allowed traders and clerks to manage their positions. “For a 20-year-old, it made a mint,” he says.

Klipp schooled his protégé in the philosophy that would become the foundation of all Spitznagel’s subsequent investing. “You’ve got to hate to make money, love to lose money,” Klipp would say, by which he meant that the key to successful trading was limiting losses by selling positions as soon as they were in the red. Don’t hang on in the hope that they’ll rebound: Dump them and move on. It took Spitznagel months to internalize the mantra, but eventually it became second nature. At the end of a day, he says, “even if I’d lost money, I would be happy going home knowing that I’d traded the way I wanted to trade.”

Spitznagel loved trading. But in the mid-1990s, sensing that the rise of electronic trading would alter the CBOT profoundly, he moved to New York and took a job as a proprietary trader with a firm called East Bridge Capital. It was another chance to practice his philosophy of being willing to lose small amounts steadily in order to win big, and when the Asian economic crises of the late ‘90s hit, Spitznagel did win big. While the Asian flu “destroyed my [trading] desk,” Spitznagel says, “it was a good experience for me, and lucrative.”

Pushed by a desire to become a more intellectually rigorous trader, Spitznagel next pursued a graduate degree at New York University’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. There, he would further his interest in free-market theory by studying its greatest proponents, the late 19th- and early 20th-century economists known as the Austrian School. Their free-market advocacy dovetailed with his libertarian convictions, but they also broadened his way of looking at investing into a way of looking at life. “Their lessons are so much deeper than just that the government should stay out,” Spitznagel says. “What I learned from the Austrian tradition is ways to think about capital and what investing really is. Investing is, to me, a key part of economic man, of how we live and what it means to be human.”

Spitznagel formed another intellectual partnership at NYU; the Lebanon-born philosopher Nassim Taleb, later famous as the author of The Black Swan , happened to be teaching a seminar there at the time. “I got this email from a fellow asking me about my [1997] book, Dynamic Hedging: Managing Vanilla and Exotic Options ,” Taleb told me. “He asked me some technical questions, which is always a good sign.” Spitznagel and Taleb were introduced by a mutual friend, and Taleb, who was starting a hedge fund called Empirica Capital, hired Spitznagel on the spot.

Asked why, Taleb explained, “Because Mark was a pit trader. When you’re a trader, you view the world very cynically—there’s no nonsense. You have to be very quick, land on your feet, find a decision—you train to be in a fire.”

Empirica opened its doors in 1999, and Spitznagel and Taleb became close partners, Spitznagel the meticulous trader, Taleb the abstract theorist. Spitznagel traded, Taleb says, “like a German engineer. He was fearless and had an iron discipline. He was into programming, building protocols—‘We buy here, we sell here, thanks, bye.’” Their approach: Build an options strategy that would lose relatively small amounts of money when the stock market rose and make huge profits if it tanked.

Their timing was excellent. In 2000, the stock market did indeed crash, and Empirica raked in profits. In subsequent years, the market turned upward, and as expected, Empirica’s returns were negative. Around 2005, Taleb, who was confronting health issues, decided that he was losing interest in the job of fund manager, and he and Spitznagel closed Empirica.

Two years later, Spitznagel would start Universa in Santa Monica, Calif. Since 9/11 Amy had been spending much of her time in Los Angeles, with one or the other flying cross-country on weekends, and though Spitznagel jokes that “the secret to a happy marriage is living on different coasts,” the situation was less than ideal. For about $7.5 million, Spitznagel would buy a four-bedroom, French-style villa from Jennifer Lopez and Marc Anthony. “I thought it was a place where I would settle down,” he says.

Again, his timing was excellent. When the stock market crashed in 2008, Universa soared—and the doomsday investor label was firmly affixed. I asked Spitznagel how he thought the government should have responded to the financial crisis. He said that the crisis was like a forest fire, the inevitable result of an unnatural event—building too many homes. The healthiest thing to do was to let it burn itself out. If you had the discipline to let nature run its course, the ecosystem would be stronger in the long run. “It would have been a bit more painful at the time—a few more banks would have gone down—but we would have been on the road to real economic recovery.

“I look like the bad guy because I think the government should allow the natural homeostatic balance to return to the economy,” Spitznagel says, “but I’m not the guy that got us here in the first place. We’re in this Catch-22 where you got us into this situation but you can’t back away because we will destroy ourselves—or so we think.” Intervention, Spitznagel concludes, creates the conditions for another fire—maybe a bigger one.

Forest fires are, of course, a close-at hand metaphor for a Californian, but the state had other issues Spitznagel worried about more. One was its onerous tax burden; the other was that the cultural mores of Los Angeles made him uncomfortable. So he moved his family to Bloomfield Hills, an affluent suburb of Detroit, and enrolled his kids in Cranbrook, the private school famously attended by Mitt Romney. He built a summer home in Northport Point, a wealthy area of Northport perched on Lake Michigan where many of Michigan’s most prominent families have vacation homes. And then he heard of a 200-acre farm in town whose owner was interested in selling—a beautiful stretch of land, with swathes of forest, abundant pasture and rolling hills from which you can see for miles. “It was extraordinary luck,” Spitznagel says. “I could see it from my beach and ponder what to do with it.” He bought the property and named it Idyll Farms. I asked him why, and in an email Spitznagel responded, “The relevant definition of ‘idyll’ is a song describing pastoral life… not to mention the overwhelming reference to ‘Siegfried Idyll,’ one of the most significant French horn passages there is, by my favorite composer, Wagner. As I roam about the farm, I hear [Wagner’s] Parsifal overture in my head.”

The previous owner had grown cherries, a ubiquitous crop in Michigan, but cherry farming there has grown so dependent on chemical fertilizers and insecticides that you can’t grow cherries anymore without those methods—and such artificial distortions of a natural process bothered Spitznagel. He considered making wine, an incipient industry in Michigan, but it’s unclear whether the state’s wines will ever compete with the world’s best, and Spitznagel didn’t want to do something he couldn’t be the best at. Cheese felt right. “It’s one of the finer culinary things we do as humans,” Spitznagel says. “There’s nothing I like more.” Plus, goat cheese is a high-end, niche market with promising commercial possibilities.

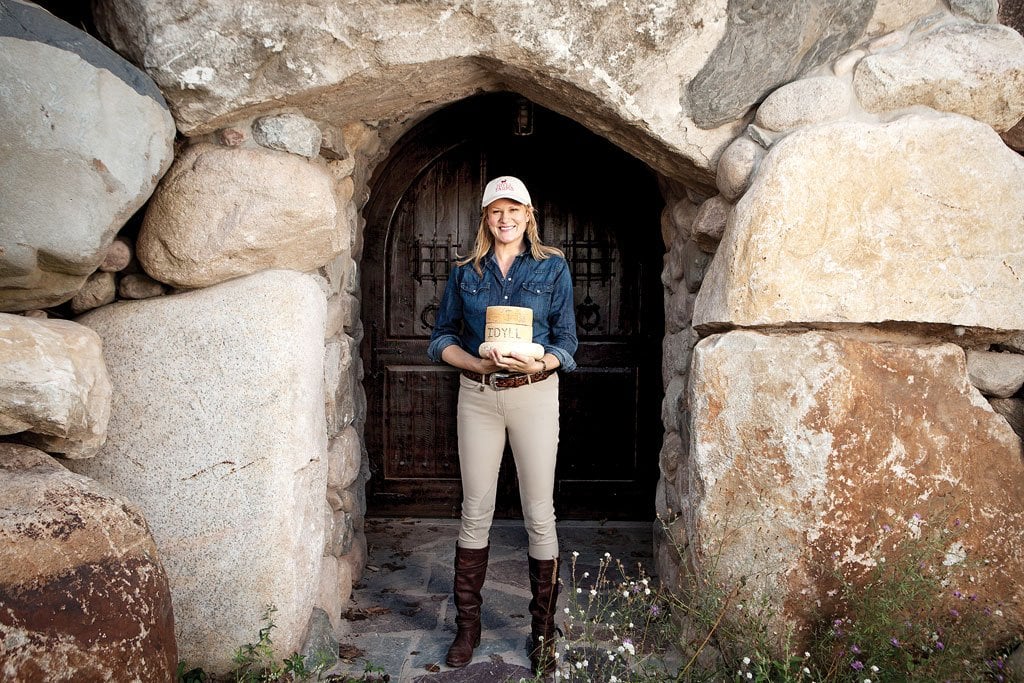

Spitznagel invested—heavily. “When I started here the only functional building was the barn that the farm came with,” says farm manager Will Manty. “The creamery wasn’t completed, the caves [for cheesemaking] weren’t done—there was no commercial operation.”

Goat farming is not a simple proposition, especially if you do it in an organic, sustainable way. For one thing, goats are mischievous. “Any opportunity they can see to escape, they will take it,” Manty says. They’re also susceptible to disease and parasites, not a huge problem if you pump them full of antibiotics but otherwise an ongoing challenge.

“We focus more on the quality of our milk and the health of our animals than the quantity of our milk,” Manty says.

Every goat on Idyll Farms—there are now about 150, a number that will probably triple over the next couple of years—has a name, not because they’re pets, but because “we try to care for them on an individual basis so that we can treat them accordingly and have healthy, long-lived, productive animals.”

“It’s just damn good cheese,” says Eric Patterson, the co-chef and co-owner of the Cooks’ House, an upscale, local-food oriented restaurant in nearby Traverse City; Patterson serves the cheese on its own or in dishes like ravioli with beef cheeks and goat cheese. Idyll Farms cheese has already won several awards from the American Cheese Society, a well-respected trade association.

Spitznagel won’t disclose numbers, but he says Idyll Farms, so far only selling cheese at farmers markets, to restaurants in Michigan and online, is profitable. I asked him what he thought Lynn Edward, who died about two decades ago, would think if he could see Mark now. Would he be pleased that his Reagan-revering son had become an organic farmer? “I’d like to think he would,” Spitznagel said. Pause. “Or would he be amused at his Wall Street son playing country squire? Those baby boomer liberals don’t always get it.”