The Monaco Yacht Club is nestled between the Mediterranean and the Monte Carlo Casino, along the curving route of the Formula 1 race course. A yacht roughly the size of a Boeing 737 bobs gently at the quay. Inside, a low-key Who’s Who of royalty, billionaire philanthropists and conservation scientists mingle over coffee on a mid-October afternoon. They are gathered for a coming out of sorts, the introduction of a petite but tough Chinese billionaire, Madame He Qiaonyu, to the global community of climate and conservation philanthropy. And He’s announcement that day—that she is dedicating $1.51 billion to conservation and the fight against climate change in China and abroad—instantly made her something akin to China’s Andrew Carnegie. “I believe that within 18 to 24 months, the initiative by He will change China into the most powerful advocate for species conservation in the world,” says Tom Kaplan, the billionaire founder and chairman of New York–based big cat conservation organization Panthera, and He’s host in Monaco. “China today, in terms of its attitude toward the environment, is similar to where the United States was a century ago.”

In the 19th century, as the United States went from a rural to an industrial society, water and air became polluted. Complete species were destroyed. “No country has a monopoly on virtue,” says Kaplan. “I plead for China not to make the mistakes that we did. To be able to collaborate with He is one of the greatest privileges in my experience as a philanthropist.” One of He’s first major philanthropic moves was a donation of $20 million to Panthera’s work on wild cat conservation.

China has been undergoing a radical transformation over the past year. In the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election as president of the United States, it has been Chinese president Xi Jinping who has stepped up as the leading global advocate of previously Western, liberal efforts such as free trade and the fight against climate change. “Multilateral trade negotiations are having a difficult time. The implementation of the Paris Agreement on climate change is encountering resistance,” Xi said at a September gathering of BRICS nations. “Some countries have become more inward-looking and less willing to take part in international cooperation, and the spillovers of their policy adjustments are deepening.”

The alignment of He’s announcement with the dramatic shift in Xi’s rhetoric in the past year is no coincidence; indeed, many of her philanthropic efforts, from sending glaciologists to the Tibetan Plateau to working to clean up rivers and build parks in China’s megacities, are in tune with the goals of the government, and with those of her business, Beijing Orient Landscape & Environment, the massive landscaping and waste cleanup conglomerate she IPO-ed in 2009. In November 2017, Forbes estimated her net worth at around $3.7 billion, a fortune forged through major government contracts such as the Shanghai Expo and the Beijing Olympics. She is now forging a path as one of the nation’s first major private donors.

For most of China’s modern history, charitable giving has been focused on urgent social needs—responding to natural disasters, providing medical care and poverty relief—but usually without any long-term strategy or professional management, as would be typical of major foundations in places like the United States. This dearth of institutional giving in China reflects decades of Communism and wariness within the Chinese government bureaucracy toward private wealth; traditionally, within the modern Chinese system, social and environmental projects have been the government’s purview. Civil society and think tanks are seen as vital checks on the government in the U.S.; in China, they have been viewed as threats.

But in recent years that perception has begun to shift, albeit slowly. “There were crowdfunding initiatives on the internet, and people were giving immediately to address some specific need—people saw the news, they cried and they crowded in to give money,” says Lu Yong, founder and CEO of Evergreen Asia Advisors and an expert on Chinese philanthropy issues for the Asia Society. This tendency toward short-termism is changing with the emergence of He.

“She is more focused on longer-term areas such as public policy and global affairs, and this represents a changing mind-set among leading Chinese philanthropists.” —Lu Yong

“She is more focused on longer-term areas such as public policy and global affairs, and this represents a changing mind-set among leading Chinese philanthropists.” Likewise, the emergence of He represents a shift at the highest levels of the Chinese government. “In the past those environmental areas were very sensitive, and they were all shut out to public participation,” says Lu. “Now the government realizes it would be nice to have private resources to partner with and someone who has the public credibility to do it. In China there is a credibility issue with government-run charities. If you have someone who is perceived to be independent, such as He, it will be better received.”

Nevertheless, He, 51, is in uncharted waters in many ways, and while freshly minted billionaires in the U.S. can look back on over 100 years of philanthropic giving and call upon established givers and an entire professional class dedicated to nonprofit and foundation management, that history and network does not exist in China. This has led He to look abroad for guidance. She met Kaplan, for instance, at the Beijing opening of the Leiden Collection, his private collection of paintings by the Dutch Old Masters. And she partnered with American luminaries Bill Gates and Ray Dalio as well as fellow Chinese philanthropists Niu Gensheng and Ye Qingjun to found the China Global Philanthropy Institute to train Chinese students and executives in nonprofit management.

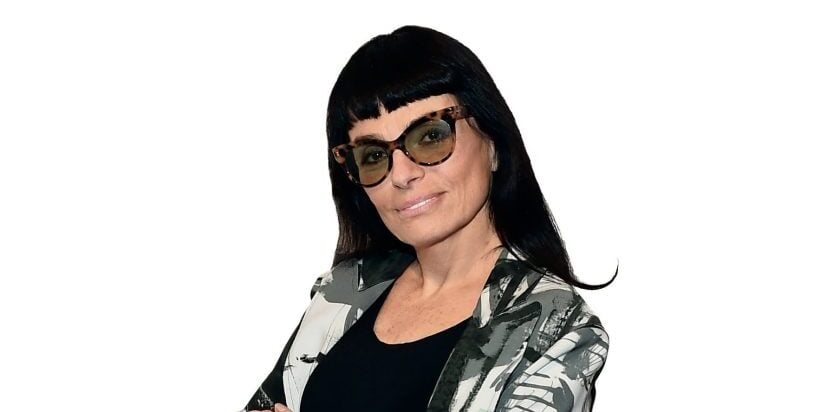

During this turbulent geopolitical moment, and as a wave of Chinese philanthropic giving begins to take shape, Worth had a unique opportunity to sit down one-on-one with Madame He Qiaonyu in Monaco to discuss her life and why she’s dedicating her fortune, and the work of her foundation, the Beijing Qiaonyu Foundation, to the environment.

Q: Why are you focusing on environmental problems in China?

A: I studied the landscape when working toward my bachelor’s degree at Beijing Forestry University. My vision at the time was to build 100 parks in 100 cities, and my teacher told us that landscape designing is a most holy and valuable thing to pursue. Over the past 20 years, my company has built hundreds of beautiful parks for hundreds of cities. But during this work, I found out that the water system has been seriously polluted so I shifted my focus to water restoration.

How did your work evolve?

During our work, we found that not only the environment of China has been seriously polluted, like water with hazardous waste, but the ecosystem has been seriously hurt as well through the shrinking of lakes and wetlands, and desertification. Climate change will have a huge and active impact on our ecosystem and society. When we started to think about that, we had to not only focus on environmental restoration but also the ecosystem. The company determined that we will restore 200 rivers in China, build 100 tourist sites to educate tourists about the environment and establish 100 hazardous waste cleanup sites in 100 cities. The goal is to promote biodiversity.

“Our vision is to leverage and engage more entrepreneurs for biodiversity conservation.” —Madame He Qiaonyu

This kind of large-scale philanthropy is new to China. Is this part of a larger trend among China’s leading businesspeople?

Biodiversity promotion cannot be done by business in China [because of government controls]. So I decided to use philanthropic power. There is a trend for entrepreneurs, like Jack Ma, to do philanthropy. All the entrepreneurs have an annual gathering, and every time we get together, we’re talking about how to promote philanthropy as a career in China.

Our vision is to leverage and engage more entrepreneurs for biodiversity conservation. I have a lot of friends now who wish to donate 1 percent of their personal wealth for conservation and to protect the environment for future generations. Because there are so many entrepreneurs in China, this 1 percent will have a massive impact. We have a lot of public enthusiasm because the probable extinction of the South China tiger in the mid-2000s and the white-flag dolphin in 2002 have been a shocking story for the public.

One thing we hear about a lot in the U.S. when we talk about the poaching of animals like lions, tigers, elephants and rhinos is that they’re being traded to Chinese for traditional medicine. Can this change?

The government is giving very clear signals that such activities are illegal. A lot of celebrities have called out the public to resist these kinds of buying activities. And we have a plan. We have the ambitious goal to do urban biodiversity habitat restoration work in 300 cities, and we will have nature education for the public as part of that.

We have another ambitious goal that in the next seven years we’ll develop a membership network of more than 3 million citizen environmentalists, and we hope this number could reach 100 million in 15 years.

Donald Trump has reversed a number of environmental initiatives in the United States, and China is increasingly perceived as the leader on environmental issues. Do you think Chinese industry and the government are prepared for this role?

For the government, President Xi has emphasized climate change issues. And when it comes to civil society…You know the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, which accounts for 20 percent of the territory in China? There were a lot of glaciers there, and a lot of those have disappeared. By 2015, [approximately] two-thirds of the glaciers were gone. These glaciers play a key role as a reservoir. This plateau is called the water tower for all of Asia, because it feeds drinking water for China and 700 million people in Asia. Solving the problems here means solving them not only for China but for Asia and the world. Now there’s a national scientific research team here and our foundation has sent two staff members to join this team on the plateau.

Your foundation talks about the environment in terms of the “services” it provides to people and the world—supplying, regulating and supporting. It’s a pretty different paradigm than you would find with Western environmental groups. It’s very integrated and doesn’t differentiate as much between people and the environment. Where does this way of thinking come from?

We have Taoism, which says we have to respect nature and follow the law of nature. We have Buddhism. We have to respect all living things; we are as one; we are equal. In the past, Western efforts have conquered nature. In the Eastern [worldview], we try to harmoniously interact with nature.

Where does that connection come from for you personally?

When I was a child [in the 1960s and ’70s], I lived in the countryside, in a very small town in the mountains in Zhejiang Province, just 11 families in the center of a valley. I ran in the mountains and forests and in the fields. Those are the memories of my childhood. That was the start of the Chinese reforms and openness policies.

Do you have a favorite place that you like to visit?

I used to travel to a lot of cities. At that time, I thought it was a paradise; they’re so wealthy, so beautiful, so artistic. But now I would love to visit Yellowstone National Park. I would love to visit the rainforest in Southeast Asia. And I’m planning to travel with Jack Ma to Africa to see the wildlife there. Now, I love to visit nature.