Perhaps the fastest-growing city in the country, Nashville has used its musical treasures to attract visitors, new residents, and businesses. But all that growth threatens to drown out the music. Here’s how Nashville is sustaining its legacy of song.

In March of this year, Butch Spyridon, the longtime CEO of the Nashville Convention and Visitors Corporation, received a phone call from a local music lover named Joe Chambers. The founder of Nashville’s Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum, Chambers wanted to warn Spyridon that one of the city’s most important musical sites was in danger of collapse. “You should go look at the old Club Baron,” Chambers said. “It’s in terrible shape.”

Most visitors to Nashville probably haven’t heard of Club Baron. After all, it hasn’t even been a venue for music since 1968, when it became Elks Lodge #1102. But back in the 1950s and ‘60s, when a wave of small music clubs was bringing energy and income to Jefferson Street, a thriving Black neighborhood, Club Baron was rockin’. As Black musicians traveled across the country on the famous Chitlin’ Circuit, they all played Club Baron: Fats Domino, Aretha Franklin, Etta James, Muddy Waters, Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix. Imagine, in 1963, a 20-year-old Hendrix, jamming at the local hangout down the block….

But over the decades, Club Baron fell into disrepair. Though the stage where Hendrix played still existed, the roof was leaking like a storm drain. “For decades we’d heard about Club Baron and its legacy, but we kind of took it for granted,” Spyridon admitted. “So we contacted the Elks and went over to take a look.” What he saw alarmed him. “When it rained, there was probably more water inside than out.”

Working with members of the Elks, Spyridon quickly launched a fundraising campaign, kicking it off with a grant from the CVC itself. So far, the CVC has raised and spent over $300,000 to preserve Club Baron, with more on the way. Still, Spyridon knows that the Club Baron crisis is just one of many similar situations around Nashville, and after 25 years of spearheading the marketing of Nashville as “Music City,” he knows that the preservation of such cultural icons can’t be left to well-timed phone calls. “If we’re serious about our brand, we have to be serious about our history,” Spyridon says. “And if we’re serious about our history, we have to be serious about preserving those key iconic venues that tell the story.”

Sustainability has become such a ubiquitous buzzword, it’s possible to use the term without really considering what it means. Most of us think of sustainability as environmental preservation. Can we continue to burn fossil fuels? Eat meat? Drink water from plastic bottles? People in the academic and NGO worlds also think of sustainability in economic terms—building a society and an economy where everyone can prosper.

But there’s another, less well-known application of the concept: cultural sustainability, the preservation of culture in the face of modernization, globalization, and economic development—all the forces of change that threaten to steamroll our past.

Institutions such as the United Nations and the Smithsonian Museum typically talk about cultural preservation in the context of marginalized and persecuted indigenous people, like Amazonian tribes or Native Americans. However, academics, activists, and policymakers are increasingly looking at cities and advocating the need for cultural preservation in the face of growth and gentrification.

At the same time, in cities around the country, folks in jobs like Butch Spyridon’s, especially in so-called second-tier cities, are leaning into culture as a way to brand their market. For Nashville and New Orleans, it’s all about music and food. For Charleston, Richmond, and Savannah, it’s history and architecture. (And food.) For Asheville and Boulder, it’s the outdoor lifestyle. (Also, food. And pot.)

The economic thesis? Authentic culture attracts diverse, often affluent visitors, and that leads to population growth and new business. In Nashville, the strategy has worked brilliantly. Over the past decade or so, Nashville has seen a surge in population growth, constant downtown development, and the arrival of new corporate outposts from hip start-ups such as Lyft and tech giants like Oracle. In 2020, Nashville was responsible for almost 40 percent of Tennessee’s gross domestic product. Its economy was larger than that of 15 U.S. states, including Hawaii, Mississippi and Vermont.

The problem, says Jerold Kayden, a professor of urban planning and design at Harvard, is that while culture can foster growth, too much growth can overwhelm culture. Growth can attract tourists and new residents with little appreciation of or interest in the city’s origins; higher housing costs, gentrification, and commercialization of authentic culture. The other industries that culture brings can also redefine a city’s image. (Just ask Austin, Texas, once proudly counter-culture and now corporate, congested, and expensive.)

“In this tension between economic development and authenticity, the authenticity piece can get crushed,” Kayden says. “The story gets stolen if you will. It’s not about sustaining the culture for its own sake, so much as sustaining the culture for economic purposes.” This balancing act—marketing culture without degrading it—is one of Nashville’s biggest challenges, and city leaders know it. For Nashville, building a sustainable future means marketing its history without losing its soul. And that means effective, heartfelt preservation.

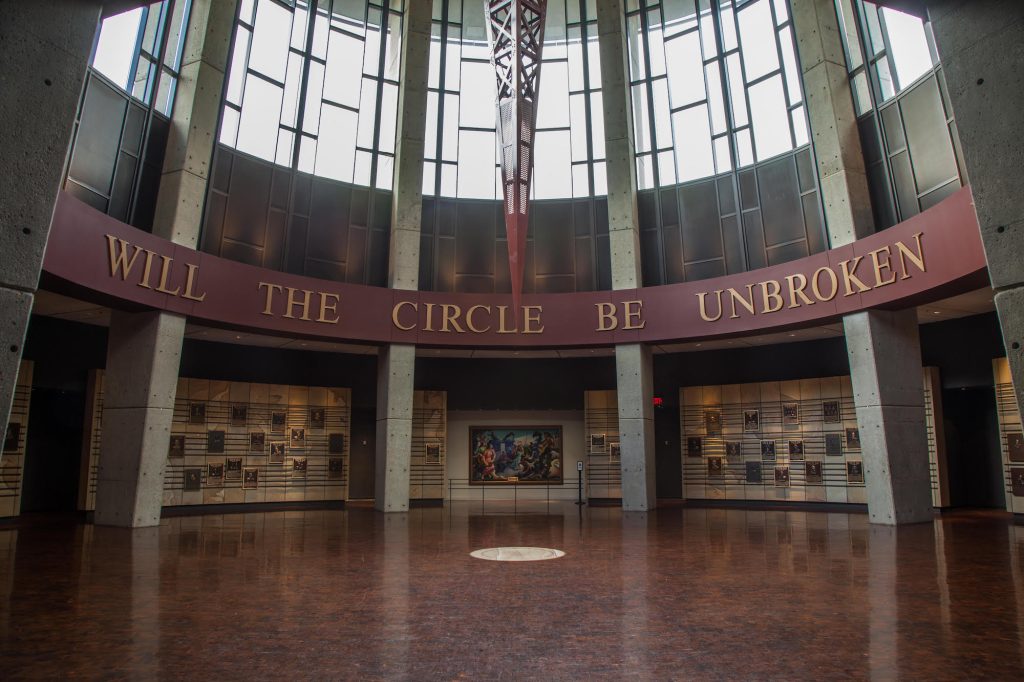

In the rotunda of the Country Music Hall of Fame in downtown Nashville, there’s a six-by-ten-foot mural by American painter Thomas Hart Benton called “The Sources of Country Music.” Commissioned by the museum in 1973, the painting portrays a barn dance with fiddlers and square dancers, women with Protest hymnals, “mountain women” of Appalachia with a dulcimer, a cowboy with a guitar, and a Black man playing the banjo. While several Black women in the painting’s background dance on a riverbank, a train—that classic image of onrushing, obliterating progress—races in front of them. The painting, says Lisa Purcell, the museum’s senior vice president of external affairs, tells the story of “an art form that is uniquely American, that talks about ordinary people and the confluence of their experiences.”

Founded in 1967, the Country Music Hall of Fame is the anchor of Nashville’s musical preservation. It’s a hugely popular museum, attracting around 1.3 million visitors a year and generating an estimated $80 million in economic impact for Nashville annually. But it’s also a serious scholarly institution whose experts appreciate the expansive importance of their material. “The history of country music is the foundation of Nashville itself,” says Kevin Fleming, the director of library and archival collections at the museum.

The Hall of Fame houses some 46,000 square feet of archival materials, including over 500 musical instruments, around 2000 textiles (many of them stage costumes), about half a million photographs, a moving image collection, a record collection that includes over 98 percent of pre-World War II country music 78-rpm records, and an oral history database.

“We’re fortunate to be located in a town where so many of the practitioners live,” says Purcell. “The commitment to carrying this culture forward is huge.” One example: The museum sponsors songwriting camps for children. The kids come from all over the country to work with professional songwriters at the museum to learn their craft. At the end of their camp, many of the students record their songs and leave with demo recordings.

Preserving a living art form means that the museum acquires some unorthodox additions to its collection. On Nashville’s Music Row, the famous home of numerous recording studios, the Hall owns and maintains RCA Studio B, one of the temples of country music history. Studio B opened in 1957, and before it was sold by RCA twenty years later, it had become hallowed ground; among the artists who recorded there were Chet Atkins, Roy Orbison, Dolly Parton, Charlie Pride, and Elvis Presley, who recorded about 240 songs there—more than he did in any other studio. Today, Studio B gets about 100,000 visitors a year, according to studio manager Justin Croft. “The emotional reactions we get from a lot of our guests are pretty powerful,” Croft says. “If someone has a certain connection to a song and they hear it…people cry, or get up and dance.”

But Studio B isn’t about nostalgia; it’s still a fully functioning studio, often used for recording by local high school bands and jazz ensembles. “Equipment needs to be powered up” to keep working, Croft says. “Pianos need to be played.”

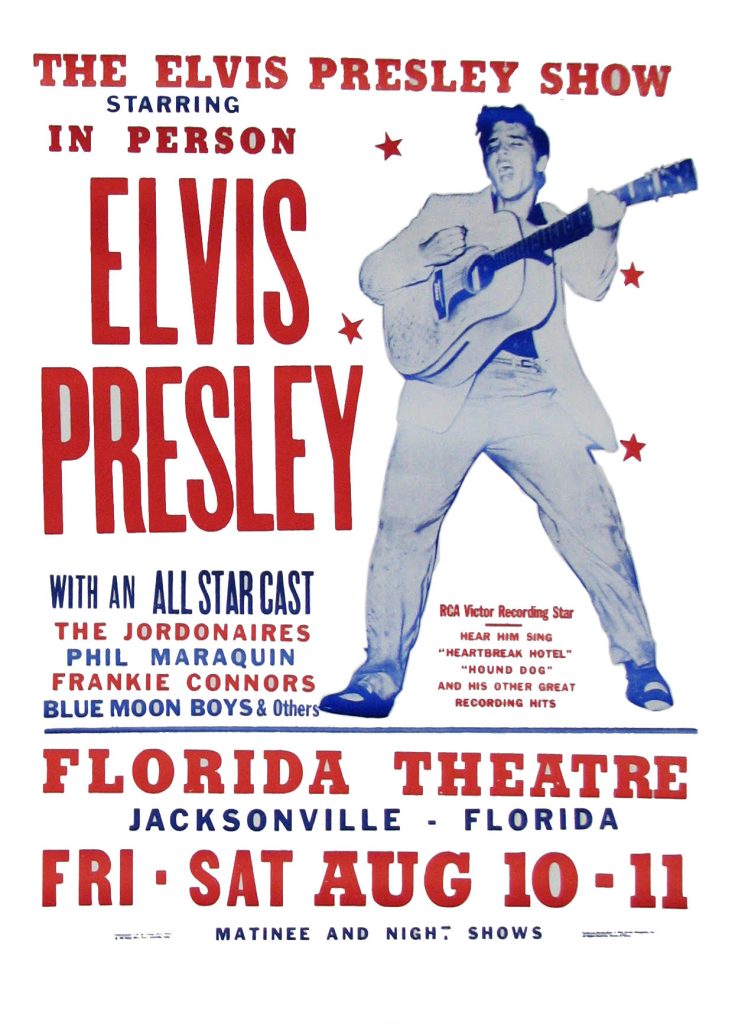

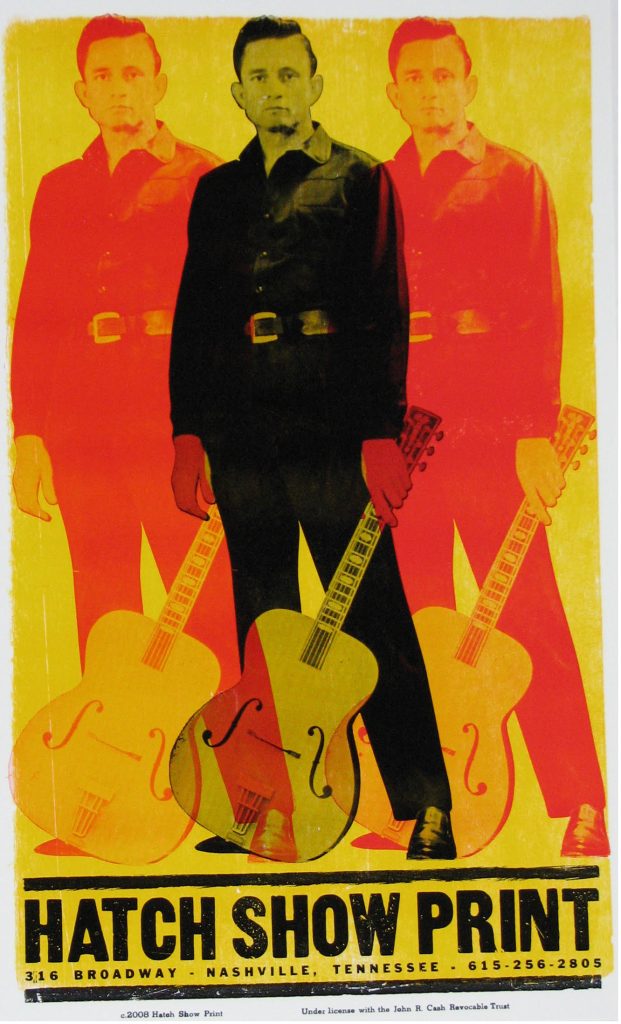

That use-it-or-lose-it philosophy is equally in evidence at Hatch Show Print, a letterpress printing shop that is also owned and operated by the Hall of Fame. Opened in 1879, Hatch Show Print began life as a printer whose founders, Charles and Herbert Hatch, launched their business by printing whatever they could. Their first poster was a 6×9” handout advertising a speech by abolitionist and social reformer Henry Ward Beecher. Hatch Show Print made posters that “told you or sold you,” says print shop director Celene Aubry. Its work included handbills, notices of church events, shop sales, and, increasingly, over time, concerts; among the shop’s best-known posters are an advertisement for Elvis performances in Jacksonville, Fla., in 1956—“Hear him sing ‘Heartbreak Hotel, ‘Hound Dog’ and his other great recording hits”— and a Johnny Cash poster from 1967.

Technology changed over the years, but for the most part, Hatch Show Print did not. Regardless of the transition to a digital world, commissioning a poster from Hatch Show Print has become a rite of passage for younger artists. In recent months, Olivia Rodrigo commissioned one for a show at the Grand Ole Opry, and Harry Styles had one made for a show he played at the Ryman Auditorium. (Another benefit: Posters are becoming an integral part of artist merchandising.) Hatch Show Print posters visually connect the present with a visual timeline of an authentic past. The Nashville Soccer Club began MSL play in 2020; it’s already commissioned multiple Hatch Show Print posters to commemorate its arrival. Non-famous people can also commission a poster by visiting the shop’s website—but demand is so high, production can take months.

Aubry points out that the wooden blocks used in printing will dry out if they’re not used, and that it’s better for the presses to use them than not. “Preservation through production is our mantra,” Aubry says.

One of Nashville’s newest institutions of preservation is the National Museum of African-American Music, which opened in 2021 after almost two decades of planning and fundraising. MAAM, as its staffers refer to it, focuses on African-American music from all over the country, but it’s inspired by Nashville’s Black music heritage, ranging from the famous Fisk Jubilee Singers of HBCU Fisk University to the clubs of Jefferson Street. “The city’s history is steeped in Black music,” says Henry Beecher Hicks III, the museum’s president and CEO. But much of that identity was overwhelmed by the commercial success of country music in the last decades of the 20th century. Until recently, Nashville’s Music City brand both reflected and inadvertently reinforced that disparity. The opening of the National Museum of African-American Music has coincided with a conscious effort on the part of the Nashville CVC and others to diversify the Music City brand and remind people that country isn’t the only genre of music that has shaped Nashville. This is both true and, from a commercial perspective, smart. Tourism and convention marketers in cities around the country are making purposeful efforts to promote more diverse attractions and attract more diverse visitors. It’s good business and the right thing to do.

“We can be easily lulled into a sense of our own racial and ethnic identity and think that that’s all that’s being heard,” says Hicks. But at MAAM, “we talk about one nation under a groove. I don’t really care what your skin color is, it’s our music, so let’s enjoy it together.” Whether it’s fixing the roof at Club Baron or trying to educate newcomers to Nashville about the city’s musical origins, Butch Spryidon agrees. “You just have to never get off message, never stop emphasizing the importance of our creative culture,” he says. “There’s no foolproof approach to doing it. We just have to be vigilant.”