“If I had a piece of paper, I would be [copying] Nancy Pelosi’s State of the Union rip-the-speech move. This election’s trash. We are living in some of the most politically toxic, racially divisive times of my generation,” Glynda C. Carr, cofounder of Higher Heights for America, said last Thursday at the Women and Worth: Power Forward Summit.

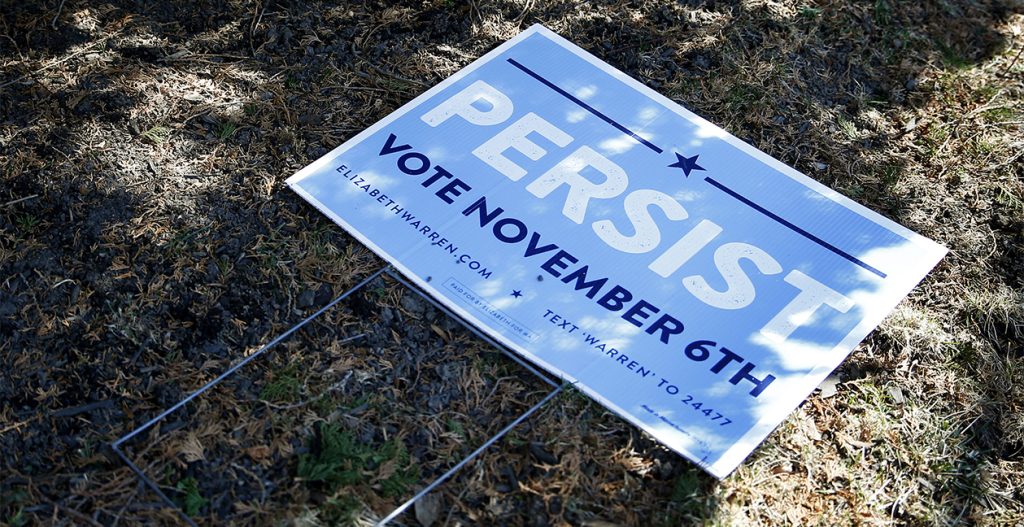

Speaking just hours after Senator Elizabeth Warren suspended her presidential campaign, Carr shared her frustration with co-panelists Ashley Etienne, communications director and senior advisor to speaker Nancy Pelosi, and campaign strategist Stephanie Berger, president of Berger Hirschberg Strategies. Convened with the hopeful title “The Rise of Women Running for Office” the discussion laid bare both the progress women candidates have made, particularly in the 2018 midterm elections, and how far they remain from achieving political parity.

“We started this cycle with the most diverse field of candidates running. The resumes of Senators Amy Klobuchar, Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris and Warren, regardless of whether you were supporting them or not, were stellar, but there were questions from day one about electability, viability and likability,” said Carr, whose organization is dedicated to increasing black women’s elected representation and voting participation. “Those are not questions and concerns that men running for office have to hear and combat.”

Indeed, coded words like “electability,” combined with media coverage often trivializing female candidates, have led to an odd and particularly exasperating moment in American politics: On the one hand, the midterms ushered in a record number of women elected officials; on the other hand, this is the second presidential election in a row in which even the most exceptionally qualified women can’t progress to the executive branch.

Whether it’s double standards in how the press covers policy differences, or the seemingly prosaic but consequential consideration of physical appearances, the media has played a major, and often unfair, role in minimizing women’s contributions.

“We spend an enormous amount of time yelling at reporters, calling every word into question, challenging them on it,” Etienne said, citing the immense attention reporters paid to the red coat Pelosi wore after she and Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) held a heated meeting with Trump over border security last December. “Even down to the red coat and glasses. It’s like, ‘No, it’s just a coat. It’s nothing more.’ We spend a lot of time on this issue of sexism in politics.”

Even when media aren’t focusing myopically on female candidates’ appearance, voters often are. In her memoir What Happened, Hillary Clinton calculated spending approximately 600 hours getting her hair and makeup done while campaigning for president.

“I’m not jealous of my male colleagues often, but I am when it comes to how they can just shower, shave, put on a suit and be ready to go,” she wrote. “The few times I’ve gone out in public without makeup, it’s made the news.”

That kind of inane focus threatens to undermine actual policy progress, Etienne said.

“Women are held to a different standard, regrettably. That’s unfair, not just to the individual, but to the larger discourse about women and politics and what we’re capable of. I’m really happy for Nancy Pelosi [to have become an icon], because it makes me feel like you never really know the full extent of a superhero’s powers until they’re up against the most perfect villain at the most perfect time. And that’s where she is,” Etienne said. “What I’ve found from her that we all need to adopt as women is how do you advocate for yourself, how do you own your own narrative and in addition to that, what I’ve learned most is that if you don’t, no one else will.”

Pelosi’s “incredibly bossed up” status, she noted, reflects and inspires the profound and important changes made possible by the record number of women in midterm elections.

“It has really been a master class for women: Not only how do you seize the table, but do how you own the table and how do you use it to your advantage,” Etienne said. “I think we’ve seen a record number of women in Congress and that’s yielded some new ground in terms of policy.”

Among the policy innovations: the creation of the Black Maternal Health Caucus, created by 33-year-old Representative Lauren Underwood (D-IL), to address the fact that black women are nearly four times more likely than white women to die from preventable, pregnancy-related complications. Or consider, Etienne said, the election of Native American Representatives Sharice Davids (D-KS) and Deb Haaland (D-NM).

“To have them talk about our country in a way we’ve not talked about it, and the amount of people who’ve been lost and forgotten, is incredible. I remember in a caucus meeting Deb Haaland came to the mic and said, ‘I don’t care where you flew from, you flew over my people’s land, Native land. This was our country,’” Etienne recalled. “That sort of perspective is powerful, and it’s become an incredible awakening within the Congress.”

The new voices, younger faces and diversity are a measure of progress in political fundraising, an area that’s long been an obstacle for women, Berger noted. Although ultimately unsuccessful, Warren’s campaign proved women can indeed be financially viable presidential candidates.

“[Before this] we didn’t have women that could fund a campaign and be able to raise multiple, multiple millions. So when I think about Senator Warren, I’m very impressed with what she was able to do in a grassroots fashion, too. She was able to compete with many of her male counterparts financially and outraised them sometimes,” Berger said. “We’ve gotten in the game. We’ve gotten the financial wherewithal and it took a long time to get to that level of parity. And now that we have that, you’re up against the bias: Are they electable, will people turn out? I’m glad we’re in the conversation financially.”

Still, even powerful fundraising isn’t enough to combat sexism, which is why PACS like Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s Off the Sidelines have become critically important, Berger said.

“We need to train women and seed the pipeline. The barrier for women is not policy. They have it down. I have women tell me, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do about the Middle East’ and I’ll say ‘you’re running for city council. You’re not going to come across that,’” Berger said. “The biggest barrier is raising money. There’s not this natural network that men sometimes have. What we’ve done is created organizations that train women to network and put it together piece by piece.”

As they grapple with yet another presidential race starring three white men in their 70s, the panelists said, those networks have to pressure both remaining Democratic candidates, as well as Trump, to pick female running mates.

“The discussion around who will be VP is an opportunity to use the same moment to reshape what electability is. What you could say is, ‘This ticket can’t win without a woman on it.’ And that is at least a leap forward,” Carr said.

For Etienne, the loss of Warren remains profound, and should prompt concerned voters to demand the remaining candidates not only pick a female running mate but adopt substantial policy commitments to women’s and family issues. “Now that we don’t have a woman in the race any longer, how does that affect the discourse around unique issues facing women and families, and how does that materialize into policies that benefit them?” she asked.

“I think there’s still an opportunity for a woman to be number two. I think we should all apply a lot of pressure on these guys to appoint a woman as a vice presidential candidate,” Etienne said. “That would still be historic and significant.”