An Oxford profession implores us, in the words of Kierkegaard, to remember the future. A bestselling author uses a scripted podcast to transform the personal essay. And an award-winning designer documents her journey to build a new kind of earth-aware fashion.

What We Owe the Future

By William MacAskill

Was it really ten years ago that Douglass Rushkoff first offered his pithy diagnosis of the prime pathology of our age, “Present Shock,” a state of anxiety caused by the ever-increasing speed and immediacy of time? It was. You’d be forgiven for forgetting. In an age of exigency upon exigency, time is measured in units of Tik Toks. Its horizon reaches barely past the next footfall. Memory is a fatality. And we are all of us living everything, everywhere, all at once—no multiverse required.

In such a daunting context, is it even possible to imagine a future beyond our moment’s favored targets of 2030 or 2050? Could we think in terms generational, or even geological, to expand the zone of our empathy to include those beyond the last infant we meet before we die? Ethicist William McAskill thinks such visioning is not just possible, but prudent, and even imperative for determining our moment’s wisest choices.

In his latest book What We Owe the Future, McAskill terms such thinking “longtermism.” If you’re allergic to academic jargon and put off by the coinage, hold steady: it belies the power of the imaginative workout he’s inviting. By demanding we reorient ourselves toward the millions of unborn who will inherit a world bedeviled by our balefulness or made sturdier by our scrupulous stewardship, McAskill forces us to the limits of our current organizing logic. Across a mere 250 pages, the reader is asked to replace, plank by plank, the valuational system in which we make decisions. By the time you hit the index, you’re looking around at a Ship of Theseus, wondering if this was the vessel you rode in on.

It’s not. McAskill is asking for a moral revolution, a fundamental shift away from the hegemony of pure economics and crass politics toward the realm of moral philosophy. His questions linger long after reading. What constitutes a virtuous social action at the timescale of civilization? How do we measure right-now difficulty against possible, imagined value? What kind of resource management is responsible if we perceive ownership to be shared across generations? For our progeny, the dents we make in the world will be their foxholes or their farms. How do we act for good now and good later—much later?

McAskill’s a Professor at Oxford, and his book is a masterclass in page-bound pedagogy. His stories are less functional than they are fractal, each an instance of a larger pattern he’s sketching for us in ink rather than chalk. His charts are fresh and provocative. His formulas hover above the obvious before distilling into insight.

A long-time evangelist for Effective Altruism, he pulls out a few of the greatest hits of the movement, introducing the fundamentals of practical do-gooding for the uninitiated. These refrains provide helpful real-world wayfinding for those oriented toward action, but it’s the new tracts that reverberate with frightening resonance. (Dare: Read the chapter on AI and “value lock-in” and try to think about anything else the rest of the week.) What is high stakes for Future Them is often high stakes for Tomorrow Us, too.

Deep within a mountain in the deserts of west Texas, engineers are laboring to construct an immense mechanical monument called the Clock of the Long Now. Intended to keep accurate time for the next 10,000 years, its chimes will play a different song each day across ten millennia. One wonders what McAskill would say of the instrument as a provocation, a promise, and a pretty good starting place for the kind of ethical imagining that asks not only who will be around to listen, but how they might be doing when the bells ring. Will the sounds reach happy ears that recall us, in Jonas Salk’s words, as “good ancestors”? The answer is one we owe ourselves as much as the faceless billions to come.

My Mother Made Me

By Jason Reynolds

No one can say definitely when podcasting was born, but we can generally agree on when it was left on our doorstep: 2004. At 18 years old, podcasting’s well past puberty, and the voice changes have begun. While Spotify goes all in on Kardashian and Markle and Audible chases the Obamas–the Blockbuster model at its finest–there is a growing contingent of audio counterprogramming that relies less on the questionable premise of famous people being interesting and more on what has made content compelling in any media in any time: great writing.

This year’s Tribeca Festival made it clear the voice box was evolving; by focusing for the first time on scripted audio content—storytelling sharpened on the page before mouth meets mic–Tribeca platformed a trend running parallel to the chatty, extemp programming that tops the download charts. Requiring a different level of narrative artistry and an elevated production quality, these scripted series, often short-run, introduce a welcome change in tone and issue a quiet invitation: If you tire of the strained banter, turn to something beautiful.

You’ll likely only need a few minutes with Jason Reynold’s luscious baritone to understand the appeal of scripted podcasting. And by the end of the painfully short season of “My Mother Made Me,” you’ll likely believe the entire podcasting enterprise was built for such an artist at such a time. The bestselling author of numerous award-winning books, Reynolds is a performer in the way few writers are, a compelling vocal artist and heartbreakingly vulnerable diarist, who marries script to speech in an alloy so harmonized it nearly casts a spell.

The ostensible subject of the 4-episode arc is Reynolds’ mother Isabell, a 76-year-old firebrand whose wisdom is telegraphed in a simple honesty that Reynolds captures with delicate recordings, dropped in the interstices of his personal essays. She is, he writes, “a woman who struggles to take a selfie but clearly doesn’t struggle to see herself,” whose clear-eyed look at life and work, love and loss, past and future, bring clarity to a son fidgeting with fame and middle life. Their sculpted conversation forms a seedbed for meaningful and melancholy discourse that somehow feels at once both universal and deeply personal.

And this is where Reynolds and his Radiotopia producers knock us for six. In a podcast format that would, in any other hands, have been output as a back-and-forth interview, Reynolds uses the format as his playground for musings both playful and prophetic. His effective, surprising prose carries you along each half-hour episode, an amalgam of diary, spoken word, journalism, therapy, and poetry. “Home is where I cut my teeth, lost my teeth, grew new teeth. And where she taught me to eat the world.”

For those who wonder what legacy-leaving ought to look like, here is an artifact to study, a story of how “the young get older, and the older get wiser, and the wiser sometimes find wonder again, before whatever comes next.”

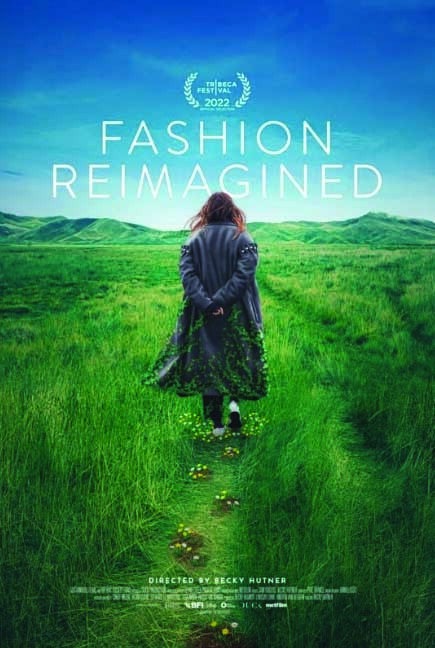

“Fashion Reimagined”

Directed by Becky Hutner

The official film poster for “Fashion Reimagined,” a captivating study of award-winning designer Amy Powney’s efforts to build a fully sustainable luxury clothing brand, is strikingly void of fashion altogether. Walking toward a horizon of England’s greenest hills, Powney is seen from behind in an oversized gray trench, English Ivy snuggling her ankles, daffodils and dandelions sprouting from her every footprint. She is either one with the land or disappearing into it. Either, Powney would say, are better options than the fashion industry’s current posture of extraction, exploitation, and evisceration.

If the image is meant to evoke a fairytale clash between good and evil, and a young princess called from obscurity to redeem the kingdom, the visual design team deserves applause. A daughter of rural England, emerging form a childhood lived off-grid with no running water and only her father’s hand-built wind turbine for electricity, Powney’s an unlikely figure to ascend the elite staircase of the London fashion scene. Yet there she stood in 2017, a rags-to-riches archetype, named top emerging designer in the UK by Vogue, given a cash award to pursue her wildest dreams, and named Creative Designer of Mother of Pearl.

Like all good heroes, Powney’s origin foretold her destiny. Soon after her coronation, her journey through the wilderness begins. The mission: build an alternative reality, a fashion collection that manages its value chain sustainably–from field to finished garment–weaving together the ethos of her ecological roots with the polish and prestige of global luxury goods.

She arrived not a moment too soon, with the kingdom, such as it is, rotting from within. 100 million items of clothing are produced every year, satiating the endless appetite of the beast–from fast fashion to high-end cult products–with 3 out of every 5 in a landfill within one year of purchase. And that’s only the end of the chain. The beginning and the middle are riddled with surpassing evils: deforestation, human trafficking, chemical waste, and endless streams of plastic. Silver-tongued capitalists call these “negative externalities.” Powney calls them something else: “complete, utter nonsense.”

And avoidable. Far from necessary evils and acceptable compromises of growth, scale, and affordability, the planetary and human vices baked into our current models of production are not required practice. There is another path. Powney walks it. And thanks to Becky Hutner’s unassuming direction that keeps her subject front and center, with a gentle editorial touch that makes the camera feel companionable, we walk it with her. To Uruguayan sheep pastures, to Austrian garment factories powered by steam, and finally back to London, where Powney pieces together a new reality of responsible sourcing, making, selling, and buying that’s received with the ovation it deserves. A fairytale ending for the film. And a gauntlet thrown before all those who have not yet found the courage to follow her flowered footsteps.