The historic election of Kamala Harris as America’s first female, first Black and first Asian American vice president was a much-needed boost after 2020’s exhausting and arduous political cycle. However, women are still massively underrepresented in elected office at all levels of government; according to the Center for American Progress, only 26.5 percent of white women and 4.7 percent of women of color hold elected leadership positions despite making up more than half of the U.S. population.

“There should be more women because elected officials should look like all of our communities,” Lucy Lang, who’s currently running to become Manhattan’s first female district attorney, told Worth. “There should be more women. There should be more people of color. There should be more Asian American, Pacific Islanders. There should be more LGBTQ+ people in leadership because our leadership in our democracy should reflect the full wealth of our cities and communities.”

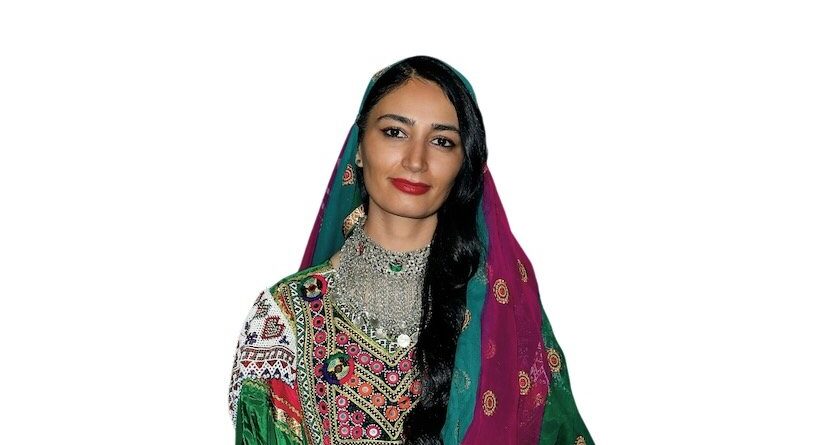

Lang, who spent 12 years working as a prosecutor in the Manhattan DA’s office before leaving in 2018 to lead the Institute for Innovative Prosecution at John Jay College, had dedicated her career to criminal justice reform and upholding racial and gender equity—just two of the issues she’s promised to tackle if elected to office. Through her dedication to serving—and listening to—communities, her passion for “dignity, equity and safety” shines through—even winning her an endorsement from the victims of Harvey Weinstein.

Worth recently had the chance to speak with Lang about being a first-time political candidate, her policy priorities and women running for office.

[Editor’s note: While the Democratic primary isn’t until June, the deadline to donate to a candidate’s campaign is January 11.]

Q: What made you want to run for Manhattan district attorney?

A: There’s no short answer to a question like that. I am running to realize the full potential of what the office of the district attorney can be. Many people think that the district attorney is the equivalent of a prosecutor when, in fact, prosecution is just one piece of what the district attorney can do with and for communities. I’m running to prioritize prevention and healing to uphold racial and gender equity and to promote the dignity of all New Yorkers.

In working to reform the system from both inside and outside of the system, I’m the candidate who’s best equipped to implement the overdue transformations that criminal justice in Manhattan needs. In terms of the personal decision, I could never have imagined that I would be a 39-year-old mom of two small kids running in a pandemic while simultaneously homeschooling.

And, of course, I have nothing to compare it to, but in some ways, it is a great environment to be a first-time political candidate because even when I do multiple events an evening for the campaign, I can usually squeeze in a bedtime story somewhere in between. That’s something that would not be true in a non-pandemic environment.

So, I take that as a piece of good fortune, and there is incredible privilege in running for office because the job is to engage with community members from all communities. And, of course, in Manhattan that is a huge diversity of rich communities who have wildly different views of what justice looks like. I get to spend my time talking to people who care deeply about the future of the city. And that is just another piece of good fortune.

You have quite a few priorities listed on your website, and they’re all very important issues that need to be tackled. So, what’s the very first issue you plan to really set your sights on if you’re elected and why?

It’s not a glamorous thing to say, but the first order of business is the question of personnel and ensuring that the people who are implementing the policies outlined in those priorities and the transformation the public is calling for are mission aligned. And that we are able to operationalize the alternatives to incarceration, the strategies to shrink the criminal justice system and the policies that will end racial disparities at different points in the criminal justice process.

That’s very important stuff. You talk about ‘cultural humility’ training. What does that mean, and how is it beneficial?

We used to talk about it as ‘cultural competency’ training. I have come to realize the hubris in thinking that we could ever be fully competent in the full diversity of cultures that constitute our city and our country. And so, cultural humility training is about teaching people to recognize what they don’t know about other people.

In this context of criminal justice, one example of that is taking a survivor-centered approach to when people are victimized and asking people what their needs are and how they can best be supported—and then responding to those needs. It’s recognizing that people bring to bear all of their lived experience in how they respond to trauma, for example, in the criminal justice system, and that it’s deeply informed by where people come from, how they had been acculturated to respond to particular kinds of treatment, to particular use of words and being sensitive to that, mindful of it and supporting people based on the diversity of the cultures that come through New York’s criminal courts.

I’d love to hear a bit more about the training class that you created to help incarcerated students. Is that something that you plan on expanding or taking to the next level if you get elected?

Very much so. A number of years ago, when I was serving as a homicide assistant district attorney, a young man was shot and killed on Super Bowl Sunday by two masked gunmen. [I] became close to his mother during the course of the investigation and ultimately the prosecution of the two people who were arrested for his murder. And they were convicted after a lengthy jury trial.

I called the mother of the young man who had been killed the day after the verdict and asked her how she felt. And she said, “I slept all night for the first time since my son was killed. But when I woke up this morning, all I could think about were the moms of those two boys.” And as a fairly new parent myself at the time, I realized how much the system was built to encourage blinders about the ripple effects of every decision that assistant district attorneys make.

And so, I thought about the best way that I know to bridge divides, which is through a kind of seminar style education and built a college in prison class that brought assistant district attorneys inside of New York State prisons to learn alongside incarcerated students and work collaboratively to develop ideas for policy change.

I taught that class to 80 assistant district attorneys in the Manhattan district attorney’s office and as DA, will make that required training for all 500 of the attorneys at the office. The program has been replicated by the Brooklyn district attorney, is being replicated by other DA offices nationally and is largely considered a gold standard in prosecution legal education.

That’s incredible. What is the biggest thing you dream of accomplishing if you become the Manhattan DA?

You no doubt know that we are the most incarcerating country in the history of civilization and that there are 2.2 million people incarcerated in this country. I have chosen to dedicate my life to addressing that problem because I have had the privilege of serving inside the system and outside of the system and working to reform it. I believe that we can solve mass incarceration in my lifetime. As long as I think that it is possible and that I can be a part of making that happen, I think it is necessary that I be a part of making it happen.

How do you feel about possibly becoming Manhattan’s first female district attorney?

We know that women leaders bring a different lens than male leaders do, and there has never been a female district attorney in Manhattan. In fact, in all of New York City in the five boroughs, there’ve been more than 300 district attorneys since the city was founded and only three of them have been women—across all five boroughs, across these centuries.

The city is far behind, and Manhattan is long overdue. I know that I will bring to it the sense of fairness, the concern about the families that it requires. But beyond that, I think I bring the lens of a parent, of someone who has deep expertise in the system, but who also sees my own children in everyone who is victimized and everyone who comes through the system. And I think that sense of empathy is something that women can bring to leadership positions which has the potential to really revolutionize the way social systems operate.

What advice do you have for others who are interested in becoming first-time political candidates?

I would encourage anyone who’s thinking about it to do it. As I was saying initially, I feel every day like I am working towards putting myself in a position where I can be of the best possible service to my community based on my professional experience and the amazing lessons and learnings that have come from my work alongside incarcerated students, victims of violent crime and community members across the board. It is a profoundly moving experience every day to feel like you are working towards that and to talk to people who believe in you and support you and go out of their way to share their message and share your message. So, I would encourage anyone who is considering it to get involved at any level. From the school board to the Senate, we need more women.

Once you take the plunge, I don’t think you’ll regret it. Maybe I’ll be kicking myself for saying this months from now, when I’m still on the campaign trail, but, as of now as a first-time candidate, it is really both a humbling and energizing experience.

Are there any particular women in politics who you’ve looked up to as inspiration?

The district attorney of Chicago, Cook County in Chicago, Kim Foxx is a great inspiration to me. There are a number of women prosecutors across the country, and in particular, a number of Black women prosecutors who are changing the way criminal justice gets done in this country. And I see them as great inspirations in my work, not just because of what they are actually getting done on the ground, in terms of transforming criminal justice, but also because of how much they have to put up with in order to do it.

I think about the distinction between the white men who identify as progressive prosecutors and Black women who do, and the vitriol with which the press and the public treat the latter is really appalling. Aramis Ayala, [the state attorney for the Ninth Judicial Circuit Court of Florida], received a noose in the mail. Kim Foxx has had to walk past neo-Nazis on the walk from her car to her office.

The kind of harassment that women of color in particular have to endure, to undertake in these positions that will enable them to make the overdue changes to criminal justice, is absolutely outrageous and goes to why we all need to support those women. And also continue to elevate all women who are willing to take the courageous step to run for office.

Definitely. What would you say to someone who believes in everything that you stand for and wants to help? What’s the best way for them to support you right now? Donate? Share your message? What do you need?

The ultimate goal is to get more votes than the next person in the June primary. Anything that helps me connect with voters is a huge help. At this early stage of the campaign, the most important support is financial support that will enable us to do the voter contact that we need.

This is a state race, so there are no matching funds. And the individual cap is $36,105.25. I am grateful for any support that people are willing and able to give. It is long overdue that we have a woman in this office and long overdue that we had a district attorney who is committed to racial and gender equity, to dignity and to safety for all of our communities.

I agree! Before we go, was there anything that I didn’t cover that you wanted to address?

I hope that folks who are the policy wonks of your community will take a look at the policies that I built out on my website. And I will just flag that they’ve all been created in collaboration with communities; I have a kind of co-creation model for the development of policy. And it comes from the work that I’ve done in prisons with the people most directly impacted by the system.

I have very close advisers to the campaign who have helped me think through everything from the revamped sex crimes unit, which I built in collaboration with the survivors of Harvey Weinstein, to the mission-aligned metrics, which is informed by my work with formerly incarcerated community members. So, everything comes from a process that is inclusive and community building, and I will bring that process and that commitment to the district attorney’s office as well.