This article originally appeared in Worth.

For nearly 20 years, nobody other than hotshot military pilots has been able to fly supersonically. But a startup out of Reno, Nevada, is aiming to change that—and they’re just a few years away from debuting their new jet.

The basic physical laws of aerodynamics have served as a universal leveler since 2003, when the supersonic Concorde was retired. Everybody, whether in the fastest corporate jet or a commercial jet, has been limited to the maximum subsonic cruise speed of around 660 mph, or a good deal less than that for most of us.

But it’s not part of human nature to accept a barrier once broken. And the daily Concorde flights between New York and London, cruising at 1,300 mph, created an elite passenger group who loved what they called “the rocket”—crossing the pond in just three and a half hours.

Inevitably a banished privilege became seen as a market that needed to be met. The problem was that, in order to meet it, the factors that killed off Concorde had to be surmounted.

The only crash of a Concorde, in Paris in 2000, killing 113 people, was a setback but not in itself terminal. The business model never made sense: the Anglo-French consortium that built the jet predicted a world fleet of 200. Only 14 were ever in regular service (seven by Air France and seven by British Airways) and operated more for prestige than profits.

But Concorde’s biggest flaw was that in order to reach its scorching speed its engines guzzled gas, polluted the skies and created intolerable noise at takeoff and landing. There was also the sonic boom: a window-rattling detonation on the ground caused by a shock wave created if the jet flew supersonically over land, which led to Concorde being restricted to supersonic flight over water.

Can this beast ever be tamed and made fit for travel at a time when the planet is endangered and commercial aviation is being required to seriously clean up its act?

The folks at Aerion think so.

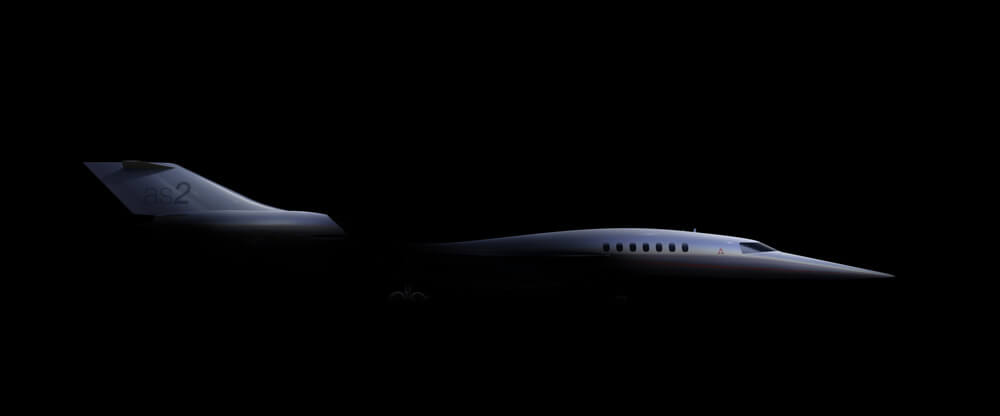

Aerion has been working for nearly a decade on a supersonic corporate jet, the AS2. It won’t be as fast as Concorde; tradeoffs have had to be made in order to find a virtuous combination of speed and much tougher environmental standards.

Getting to a viable model has been problematic: unable to fund development on its own, Aerion had to find a partner with deep pockets and even deeper technical resources. First up were Airbus, but they bailed after deciding such a niche market did not fit their future. Next were Lockheed Martin, but after a year they were replaced by Boeing, who are now driving the program.

The decisive partner, though, was GE, who are providing the engine—the first new engine for commercial supersonic flights in five decades. This was a bet on more than the AS2. GE is banking on being the sole engine provider for more supersonic commercial jets to come, possibly including a Boeing/Aerion airliner.

In the end, it will take two significant technical advances to validate the AS2 concept. The engine will have to meet the same standards for noise and emissions that are now mandatory for subsonic jets. And the aerodynamicists have to sculpt a new form that enables frictionless high speed flight that curbs the supersonic boom and needs far less brute power from the engines to reach cruise speed.

Aerion’s own strength, demonstrated in its original concept, has been in aerodynamics and, specifically, in a revolutionary blade-sharp wing exploiting a phenomenon known as laminar-flow to significantly cut aerodynamic drag. This, and other refinements, reduces by at least a quarter the shock wave that creates the sonic boom. As a result, Aerion has pioneered what it calls “boomless cruise”—meaning that it will be able to be routed over land at supersonic speed without creating a boom, albeit at less than its maximum cruise speed of just over 1,000 mph.

Aerion hasn’t disclosed the development costs, nor has Boeing put a number to its own investment. Given that the grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX will cost the company north of $16 billion, they will clearly be vigilant about the costs of this project, while betting on the value of a technology transfer from Aerion. The first flight is planned for 2023, with 2026 as the target to deliver to customers. Depending on the cabin layout, it will be able to take up to 12 passengers.

The ultimate question for both investors and would-be customers is: What advantage are you buying with a supersonic private jet?

Imagine a 4-hour flight between New York and London. Or a 13-hour New York to Singapore flight.

Aerion’s answer is time saved: an Atlantic flight time from New York to London of around four hours, saving around two hours depending on prevailing tail or head winds; New York to Moscow in around six hours, saving two and a half hours; New York to Singapore in 13 hours and 45 minutes, saving 4.15 hours.

Longer flights involve refueling stops. That is where a supersonic jet begins to lose its competitive advantage. The AS2 has a range of around 4,700 miles. The newest subsonic corporate jet, the Gulfstream G700, has a range of 7,500 miles, good enough to fly nonstop from New York to Tokyo. The Gulfstream will cruise at the upper limit of subsonic flight at 660 mph, with great fuel economy. On a similar route the AS2 would have to make a refueling stop, losing its advantage each minute while the Gulfstream is in the air.

In terms of cabin comforts there is nothing to choose between the top line corporate jets and the AS2—they are equal in luxury and space, unequal only in terms of speed. With the current technology there isn’t any prospect of a significant extension of the AS2’s range. Aerion’s business model calls for the program to be viable on the shorter nonstop flights over water alone.

That would surely be compelling enough for the pond-hoppers who yearn for the same bragging rights that Concorde delivered—“the rocket” is back!