A power of attorney is a legal document giving one person (the agent or attorney-in-fact) the ability to act or make decisions for another (the principal). In the event of incapacity or disability, it may become necessary for someone to make financial decisions on your behalf, such as paying bills, selling investments or even changing beneficiaries on retirement accounts.

Therefore, it is essential to choose an individual you trust completely, since the document grants a great deal of discretion and authority over your finances.

There are ways to create a power of attorney that offer additional layers of protection. These typically involve limiting the scope and power granted through the power of attorney when the document is created. Be sure to draft the power of attorney when the principal still has a clear mind and can limit what the agent can do with respect to various assets. The power of attorney may also be written in a way to provide third parties some oversight of the agent’s actions.

For example, you could give power of attorney to one child, but that child would have to provide a written summary of his or her financial actions to a third party (another child, a friend, a financial advisor, etc.). The power of attorney can also be written to limit the actual power granted to the agent.

It is essential to choose an individual you trust completely, since the document grants a great deal of discretion and authority over your finances.

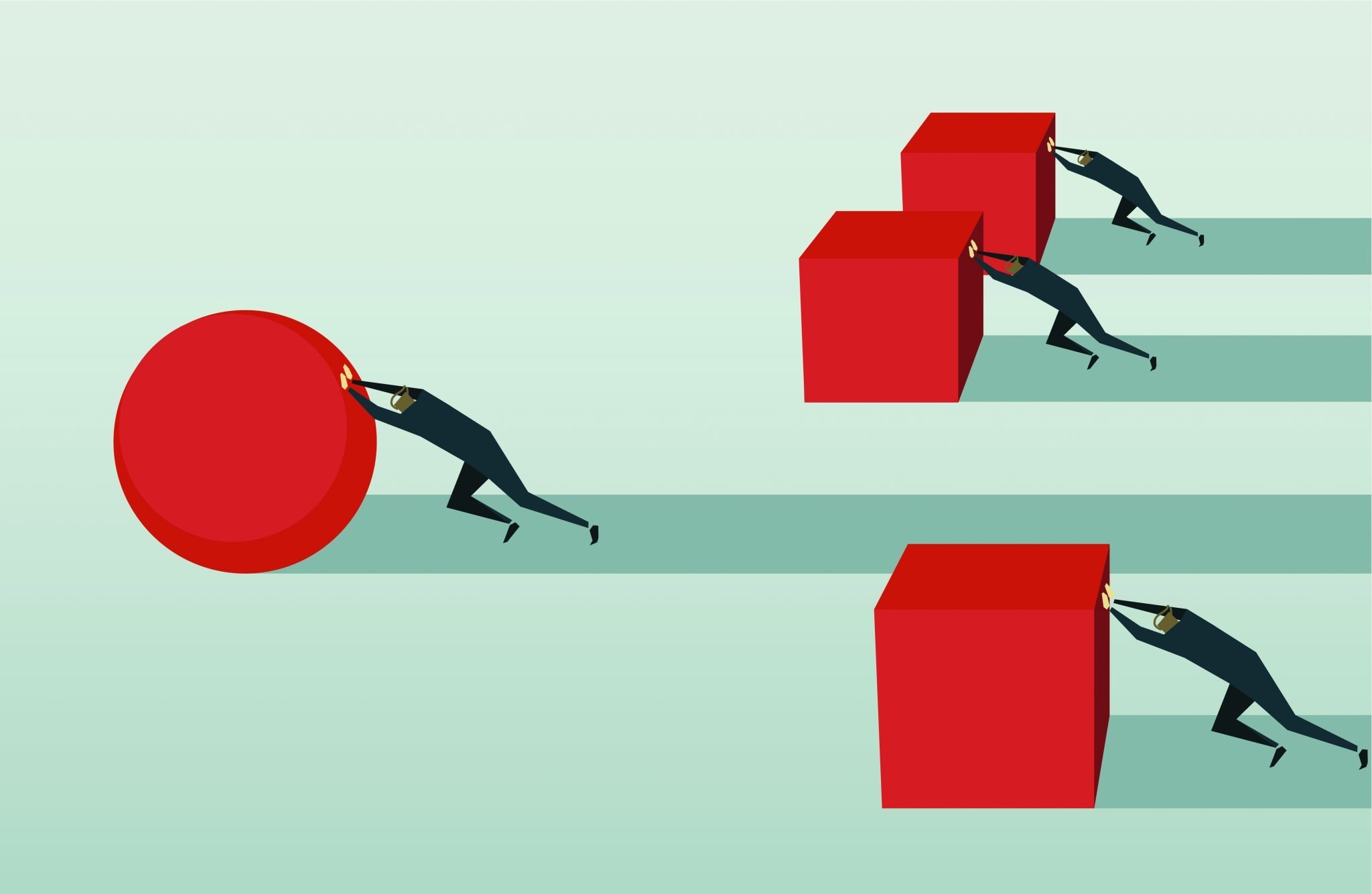

The principal could allow the agent to pay bills and manage brokerage accounts, but restrict that individual’s ability to amend wills, change beneficiary designations on retirement accounts or make gifts. In some cases, it may even be warranted to arrange for co-agents, by granting power of attorney to more than one individual. This provides oversight over financial decisions and is typically done among children or between a child and a financial advisor or attorney.

Another strategy is to create a “springing power,” which “springs” into existence after a specific event befalls the principal, such as legal incompetency. The power of attorney can make it clear how incapacitation is to be determined and what is needed by the agent to “spring” the power forward.

In many cases, the sign-off of at least two doctors could be required before the agent’s power would be granted. The downside here is the requirement to determine incapacitation. If time is of the essence, the delay in obtaining certification of the principal’s incapacity could be disadvantageous.

Often, it can be difficult to determine whether or not an agent is abusing his or her power of attorney, since the principal may not be in a position to recognize wrongdoing. The agent may argue that the intent was to protect the principal from making poor financial decisions. Even after an abuse is discovered, it is often difficult to correct what has been done.

The principal can sue the agent for breach of fiduciary duty and attempt to recover the stolen assets or seek damages for any financial wrongdoing. However, because of the complexity of the situation, recovery is not always easy and may be costly. For these reasons, it is advisable to add limitations for the agent when the power of attorney is first drafted.

Ultimately, in order to protect yourself, you should make sure that your agent is someone you trust entirely, and someone who has a good foundation of financial knowledge. It is wise to revisit your choice of agent every few years to determine whether that person remains the most appropriate person for the job. Everyone’s situation is different, and an attorney should be consulted whenever you are considering granting power over your finances to another individual.

This article was originally published in the October/November 2016 issue of Worth.