Imagine this scenario: A couple plops down side by side in front of two slot machines amid a sea of flashing light and blaring sound on a casino floor. Impatient, the husband feeds his loyalty card into the game and anxiously awaits his first wins. The machine, using personal data such as his past play, income level and demographics, doles out a series of small bonus wins to keep the man engaged.

His wife, on the other hand, goes into an almost trance-like state as she plays, seeking not the immediate gratification of small wins but a substantial jackpot to reward her patience. Sophisticated computer brains behind the machine recognize her different temperament, and after a good long while, the game gives her a big win.

She feels great—and immediately shares the news of her jackpot with her Facebook friends.

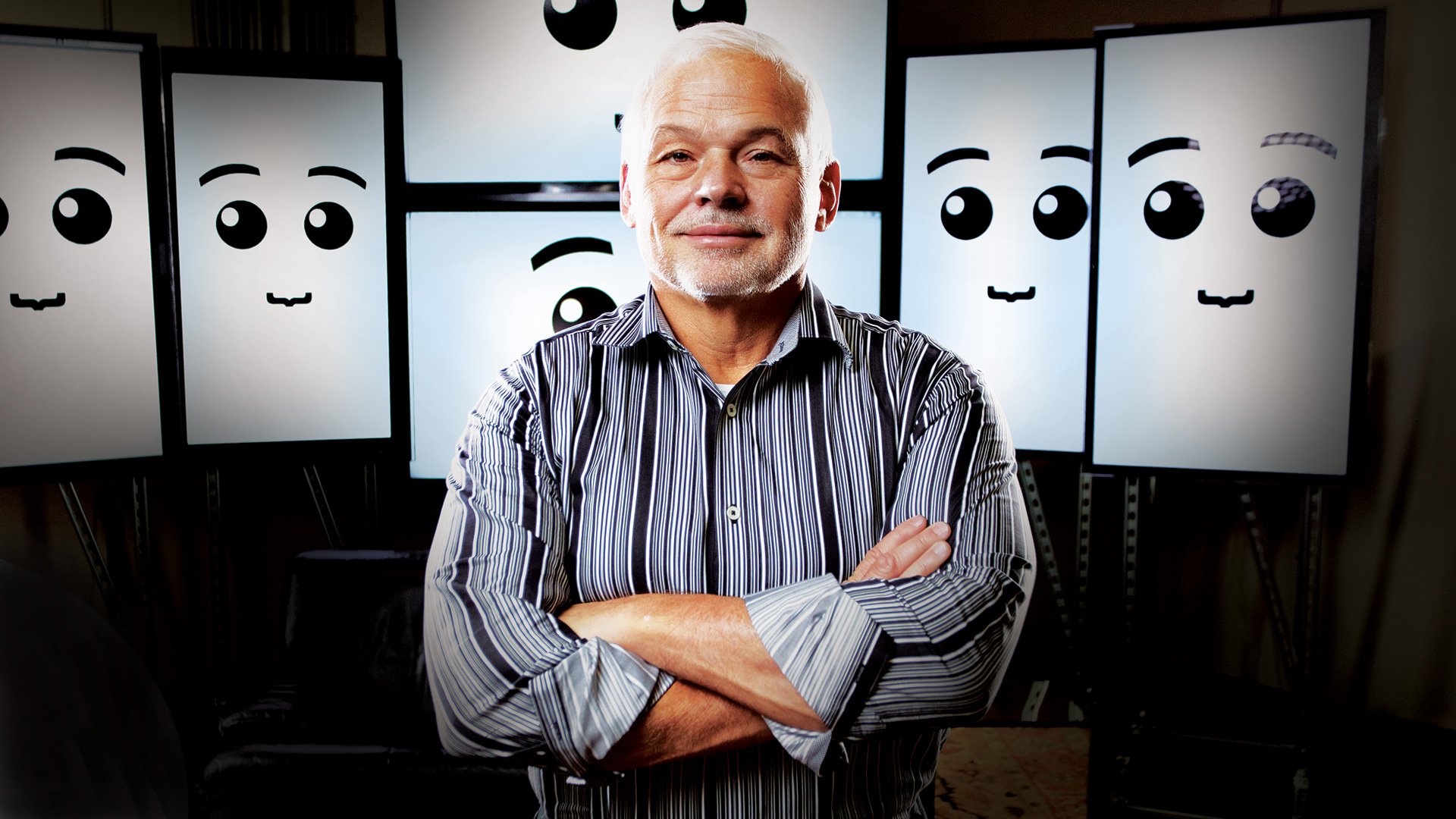

Welcome to bespoke gambling. In the casinos of this future world, machines will cater to individual tastes based on electronic profiles they gather on gamblers. The players will have more fun, and the house will make more money—a lot more. This vision comes from John Acres, one of casino gaming’s great disruptive innovators. Acres toils in the background of gambling, unseen by the public but enormously influential. Millions already enjoy his past inventions, and now he is seeking to implement his most ambitious casino revolution yet.

Acres wanted to change not how machines played for the masses, but how each slot reacted to each individual player.

Acres fell in love with gambling in 1972, when he took a job repairing slot machines at a Vegas gambling house, Mr. Sy’s Casino of Fun, to supplement his $333.60 monthly wages from the Air Force. Located across the street from the Stardust Hotel, Mr. Sy’s didn’t exactly attract the high rollers of the day. It sat in a strip mall, behind a gas station, next to a liquor store.

The 19-year-old Indiana native watched with fascination as manager Norman Little greeted customers. Little would gaze across the rows of slot machines, looking for gamblers on a losing streak. He would walk over and introduce himself. “I am really sorry for the way this machine is treating you,” he would say. “Let me help you out.”

Little would reach into his pocket, dig out a master key and open the machine. Back then slot machines still had three spinning wheels rather than video screens, and the manager would align the wheels into a winning combination. Depending on how he sized-up the long-term value of the customer, $20, $50 or even $100 in coins would pour into the bucket at the bottom.

“Thank you for visiting our casino,” Little would say.

The players still lost money, of course. But they left in far better spirits, making them more likely to return—and lose more money.

In 1981, with $200 in his pocket, Acres started his first business, Electronic Data Technologies. EDT created a system that allowed casinos to track slot machine players by using loyalty cards, offering gamblers rewards based on how much they played. In 1984, Acres sold the company for $1 million.

He started his next business, called Mikohn, in 1986. Mikohn devised the modern progressive jackpot system in which slot machine jackpots increase over time, creating growing excitement for players. When Acres and his partner sold the company in 1999, Acre’s investment of $120,000 turned into $6 million.

His third company, Acres Gaming, invented a system in which slot machines awarded instant bonuses based on current or accumulated play. Acres Gaming took $17 million to reach consistent profitability; Acres sold it in 2003 for $143 million.

With each new venture, Acres faced initial skepticism from slot machine manufacturers and casinos. Each time, he eventually convinced them to adopt his ideas. “It took over 10 years for player tracking to become accepted,” Acres says. “Now it is an essential part of every gambling organization.”

“John is not only a visionary, but passionate and persistent,” says Bryan Kelly, senior vice president of technology at Bally Technologies, the world’s oldest slot-manufacturing company. “He was at the forefront of player tracking and bonusing, as well as personalized bonusing at the point of play. He is brilliant.

Full of stories and enthusiasm, the 60-year-old Acres, with his white beard and solid biceps, gives off an Ernest Hemingway aura. He speaks his mind and prides himself on lacking any tact or diplomacy. “I’m a risk taker—I do this out of love and passion,” he says. “My measurement is not, how big a stack of money do I have; it’s, can I move the needle? Can I change how this industry runs?”

After becoming wealthy, at age 50 Acres tried retiring. He built a farmhouse in Oregon where he kept fish rather than animals. In his barn, he installed a 10-feet-deep, 25-feet-in-diameter aquarium. He stocked it with Atlantic rays, nurse sharks, reef sharks and 100 other fish, swimming in 35,000 gallons of water.

By 2007 Acres had grown restless. In his own way, he still wanted to change the world. “I’m not going to invent some major cure or eliminate the use of fossil fuels, but I can do something to help people have a good time,” he says.

So he devised his most audacious vision yet: personalized gambling. Acres wanted to change not how machines played for the masses, but how each slot reacted to each individual player. Using software Acres was developing, the slot machine would offer odds that remained the same as before—on the Strip, that’s about 92 cents returned on the dollar. But Acres’ future slots would dispense more bonus winnings and distribute to good long-term customers more often than to others.

Timing would also influence the bonus payments. On a quiet Thursday night, a gambler might see play extended, with extra bonuses, to an hour and a half. But on a busy Friday, that same gambler would receive fewer bonuses, and his play might last only 45 minutes. And because industry studies show that gamblers with early good luck are far more likely to become loyal players than those who strike out, first-time visitors might receive a quick win.

Casinos are struggling to appeal to young people who’ve been weaned on video games and the internet.

“We want to measure your tolerance for volatility,” Acres says. “How big a loss, how far through the desert can you go without water, before you give up?”

Another example: Many slot players try their luck on three to 10 machines per visit, moving once they are convinced a machine is unlucky, or after it has proved lucky several times. By studying the win/loss pattern of players who move to another machine, Acres can determine what causes a player to stay longer.

“Gambling is one of the great selfish escapes, where people can stop worrying about obligations, commitments and expectations to focus solely on themselves,” Acres says.

“And personalization allows us to treat customers as individuals rather than members of a herd.”

Acres focuses on electronic gambling for one simple reason—it’s lucrative. In the year ending last October 31, Nevada casinos made $6.7 billion from slot machines, compared to $4.1 billion from table games such as roulette, blackjack and baccarat, according to Nevada Gaming Control Board statistics.

Yet casinos are struggling to appeal to young people who’ve been weaned on video games and the internet. “For several decades now, casinos have been challenged with how to attract a younger demographic. Their player base continues to be people in their late 40s and above,” says Bryan Kelly of Bally Technologies. “The casino gaming industry is definitely concerned about this. We have seen gaming revenues drop steadily in most markets.”

“Young folks don’t want anything to do with this archaic game of watching a few reels spin,” Acres says. “They want interactivity.”

I recently asked Rich Mirman, a master of Las Vegas marketing, to join me on a visit to Acres at his latest company, Acres 4.0, on the outskirts of Las Vegas. From 1998 to 2007, Mirman worked as a top executive at Harrah’s (now Caesars), leading the company’s extensive efforts to collect customer information through its loyalty program. The slot machine card readers Acres developed earlier in his career had made all that data-gathering possible.

At Acres 4.0, Mirman and I made our way across a large open space dominated by the life-like faces of the Amazing Xandrick, Winabella and Madame Fortuna—prototype displays that might ask for your date of birth or other personal information and then suggest you try a certain machine. Acres then led us to a bar area he built to represent how casinos will look in the future; on the bar top, iPad-based slots had replaced today’s huge machines.

Over the next two hours, Acres detailed his vision to Mirman. “It’s a great creative idea,” Mirman concluded. But wouldn’t Acres’ system be a violation of current casino rules?

Mirman was right: Under existing gaming statutes, personalized gambling is prohibited. Casinos can track a player’s wins and losses in real time and send an attractive host to cheer up a big loser with a free meal voucher. But casinos cannot add extra winnings to the game results.

Acres is not worried. “John has a great get-it-done, stick-to-it mentality. I’d never bet against him,” says Joe Kaminkow, an industry legend who is now a senior executive at slot machine maker Aristocrat Leisure.

Acres has already spent $23 million—about a third of that his own money—building Acres 4.0. He has about a dozen investors, including individuals, groups and small institutions. It’s a big bet, but Acres isn’t worried. “Vision and delusion appear identical when a new idea is first explained,” he says. “Organizations always presume delusion and concoct analytics to prove ahead of time why each new concept will fail.”

Ultimately, bespoke gaming will happen because it makes too much sense and because everyone will wins from it; gamblers will have more fun while casinos and gaming manufacturers will make more money. Too much is at stake for the industry not to innovate. Already slot machine manufacturers are developing more interactive games that, for example, play gamblers’ chosen music and flash favorite pictures to make them feel at home. The easy sharing of results via social media is also in the works. Acres’ vision seems an inevitable progression.

“Throughout my 40 years in gaming, I’ve always strived to build things that foster a sense of self-worth in players,” Acres says, “Every organization in gambling has resisted.”

But as Acres knows, if you play long enough, eventually you win.