Entrepreneur Hallie Meyer is just as comfortable discussing restorative justice or the National School Lunch Program, on which she wrote her Yale senior thesis, as she is talking about empanada-eating in the Bronx, her lifelong ardor for gooseberries, the beauty of pairing apricots and butterscotch and her all-consuming passion for ice cream.

Eating ice cream should be happy and not overly intellectualized.

“I truly need to eat it every day,” says Meyer, who at 26 has created two food startups, cooked at the American Academy in Rome and River Café in London, and worked for a year as an AmeriCorps team leader in a Bronx elementary school, where she also ran an after school cooking club that made ice cream. “I’ll eat anyone’s ice cream. I feel like eating ice cream should be happy and not overly intellectualized. I’m a little bit overly intellectual about my own product.”

If she’s preternaturally mature, she’s also very much of her era. In addition to her Caffè Panna Instagram feed, which has over 5,600 followers, her “alter ego feed,” 2girls2cones, has 16,800. With another former AmeriCorps volunteer, Meyer posts daily photographs of frozen desserts throughout New York—Superiority Burger has her favorite flavors—and around the world.

Now she won’t have to travel. In September, Meyer opened Caffè Panna, an ice cream and coffee shop north of Manhattan’s Union Square, where she churns flavors like chocolate sorbet and olive oil peach, offered with a luxuriant Italian-style whipped cream that uses milk from Piemontese cows. In opening the cafe, named for the Italian word for cream, she’s stepping out of the benevolent but very long shadow cast by her restaurateur father Danny Meyer, whose many culinary successes include Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern and the Shake Shack chain.

Meyer acknowledges that being her father’s daughter has given her distinct advantages, but she’s determined to establish her own professional identity, self-funding Caffè Panna, for which she holds a 15-year lease, and hoping to generate headlines that don’t reference her famous dad. (“Home-cooked meal delivery service co-founded by Danny Meyer’s oldest daughter launches in Manhattan,” said a September 2016 Crain’s headline.) As she establishes herself in the neighborhood where she grew up, she is navigating both a part of Manhattan and an industry deeply shaped by her father and attempting to do it on her own terms.

“I’m so grateful to have grown up in a family where I was inspired to do something like this, and yet Caffè Panna is very much my own thing,” says Meyer, from the airy, 1,200-square foot space, which also includes an affogato bar for coffee drinks like sweet cream ice cream immersed in espresso and crowned with whipped cream. “I don’t ask for advice unless it’s something really big, like, ‘Should I sign this lease?’”

Still, Meyer, who shares her father’s warm smile, direct gaze and firm handshake, confesses that her confidence is a relatively recent acquisition. “A few years ago, I wouldn’t have been comfortable telling my dad that I wanted to open my own place,” she says. “I didn’t want him to think that I wanted to copy him.”

Meyer’s friends and colleagues say she’s supremely self-directed. “During our pop-ups, Hallie holds it down. She’s a hard, hard worker. She knows what she’s doing,” says Jason Alicea, who worked with Meyer at the Bronx Night Market in 2018, where she scooped ice cream while he served the empanadas he now offers in his own restaurant, Empanology. Alicea, an Institute of Culinary Education alum, says he has long admired Danny Meyer, but that “you wouldn’t put the two together if you didn’t know. She never said whose daughter she was.”

“Hallie’s got incredible energy,” says Amalya Romero Schwartz, who worked with Meyer as a City Year AmeriCorps member at PS 154 and now oversees City Year’s partnership with PS 96. “She constantly put our team’s goals ahead of her own. At City Year, we begin and end every day standing in a circle with our teams. I know she’s trying to create that at Caffè Panna. She asked me about how to organize the circle, and I laughed and said, ‘You’re going to make them do circles?’ and she said, ‘Of course I am.’”

Beyond team building, Meyer says, she’s committed to being a socially conscious employer. “I’m super excited to work with an organization called Drive Change,” says Meyer. “They have a restaurant training program for previously incarcerated 18- to 25-year-olds. We’ll have one of their fellows working here, and maybe add a second. It was important to me to make sure our leadership is also ready for that. Luckily, they provide hospitality for social justice training.”

Connecting with community is the key to success, says National Ice Cream Retailers Association executive director Steve Christensen, whose organization represents about 700 of an estimated 40,000 American independent ice cream shops. “Many shops go belly up, even with great ice cream,” he notes. “We try and educate our members that the environment in which they’re selling is almost as important as the ice cream itself. It’s how the employees are engaging with customers, how the customers feel in the shop.”

Meyer’s approach surpasses her father’s example, says Drive Change’s COO Kim Di Palo, a former Gramercy Tavern general manager. “Danny revolutionized the hospitality industry 35 years ago. He changed the way that we think about how we take care of our guests. He also very openly stated that his employees were the most important stakeholder. Hallie is building upon this mission,” says Di Palo. “Hallie was obviously raised by a wonderful family. But what really resonated with me is how willing she is to talk about these issues. That’s essential in a leader who will change workplace culture. The restaurant industry is built on systems that have come out of feudalism and slavery. We can’t undo it overnight, but Hallie’s willing to make it a priority in business operations and decisions. That takes guts.”

Meyer’s honed her courage through unexpected adversity.

In the summer before her senior year at college, Meyer and her sister, Gretchen, were leaning against an unstable fence. It collapsed, leaving Gretchen with a concussion and Hallie with a traumatic brain injury, forcing her to miss the first semester. She spent an extra semester catching up, and in characteristic fashion, also used the time to partner with Yale Law School student Khalil Tawil to create Umi Kitchen, a delivery service providing home-cooked meals to New Haven residents. Meyer, who as a freshman started the Northern Greening, a catering company for university functions, was known on campus for her culinary skills. (Though she didn’t mention it in interviews, each of her parents told me, separately and proudly, that she set a university record by twice winning Final Cut, Yale’s Iron Chef-like competition.)

“Khalil was inspired by his mother, who immigrated from Lebanon and found her financial footing in the U.S. by selling home-cooked meals in the neighborhood,” Meyer says. “His idea was ‘let’s find people in New Haven and start offering their meals and delivering to people’s doors.’” Together, they enlisted 20 cooks, ranging from an Iraqi refugee making “amazing spice chicken” to a “yoga mom” cooking Whole30 meals.

“We sold a lot of meals in New Haven, so we decided: Let’s raise money in New York and launch it here. We did the whole venture capital thing and built an app around it. We ended up having 80 cooks in the city,” says Meyer. Ultimately, though, the venture was unprofitable, and shuttered after a year and a half. “The cooks were selling meals but not enough to make the business work for us. I do feel very proud of the community that we built. They still talk to each other and stay connected in this big Facebook group.”

That sense of community, Meyer says, was especially important as she contemplated her own future and purpose following the 2016 presidential election.

“Frankly for me it was right around the Trump election. I wanted to do a year of service, which I had been thinking about throughout college,” says Meyer, who was accepted at AmeriCorps and spent a year providing academic support to students and running after school programming. In the five months between graduating and the beginning of her AmeriCorps gig, Meyer decamped to Rome, cooking at the American Academy, eating as much gelato as she could and planting the seeds for what became Caffè Panna. When Meyer completed her work at PS 154, Rome beckoned again, and she spent a month working at cult gelateria Otaleg.

“I had always been saying I wanted to have an ice cream shop, but that would be when I’m old and whatever. But when I was in Rome, I was just ‘No, I think it’s now. I have to do this,’” she says.

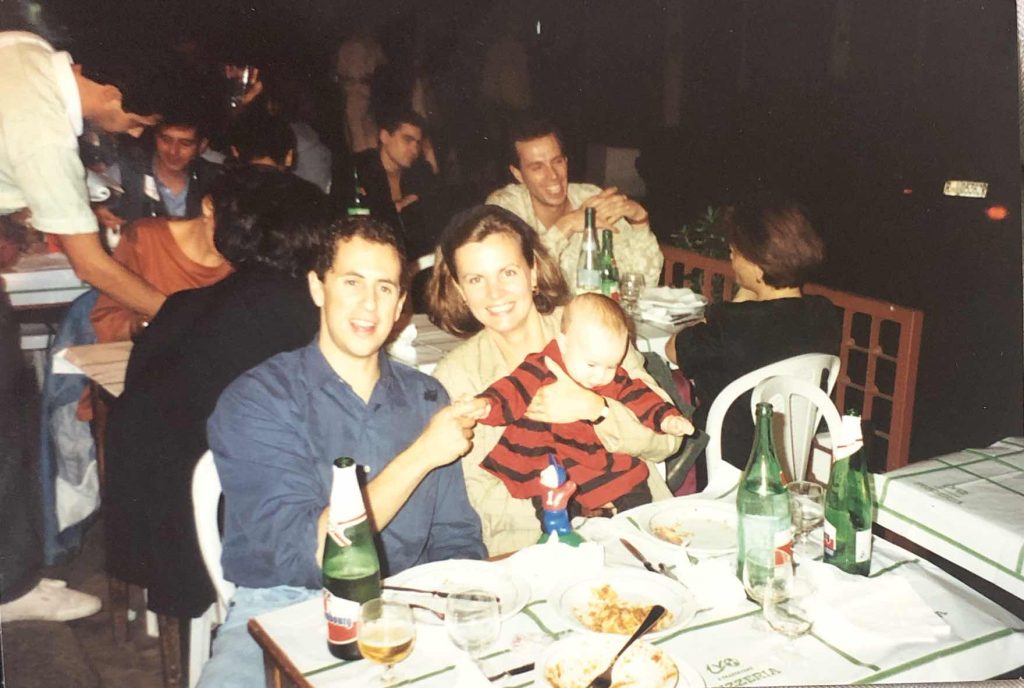

The urgency was instilled in her upbringing, watching her father create restaurants and her mother, Audrey, who took time off to raise Hallie and her three younger siblings, return to work as an actress. “The minute my youngest sibling turned 12, my mom got an agent and started auditioning again, performing in everything from Gilbert and Sullivan, to off-Broadway musical revues to television shows,” says Meyer. “Also, how exhausting must it be to be a mother of four but also be getting rejected multiple times a day and still persisting? So, she’s awesome.”

The admiration is mutual. Audrey Meyer describes her daughter as a whirlwind of epicurean generosity. As a high school student, Hallie cooked the family’s nightly dinners, her meals so satisfying that her parents hired a chef when Hallie left for college. Even now, Hallie flits through the Meyers’ Gramercy Park apartment, leaving delicious pasta and ice cream in her wake.

Hallie’s been working on this for years. She’d work 14 hours a day in the Bronx and then come home and churn ice cream.

“Hallie’s been working on this for years. She’d work 14 hours a day in the Bronx and then come home and churn ice cream. She’ll say ‘here, taste this,’… it’s almost like an assault,” Audrey Meyer says. “The other day she broke my refrigerator shelf with some kind of heavy ice cream base. And she’s like, ‘Oh, I only have five minutes, but let me make you a pasta.’ She whips up something to-die-for and then she’s like, ‘Bye, going to a meeting.’ She just gets so much joy out of feeding people.”

Her parents’ enthusiasm for their individual careers has been critical to Meyer’s approach. “The most influential part of growing up in my family was not necessarily that it was ‘open a restaurant’ but that it was ‘do what you love. Use your life to gain the skills necessary to do what you want to do,’” Meyer says. She tackled her idea with the joie de vivre and academic zeal that propelled her through New York’s prestigious Brearley School and throughout Yale, attending Penn State’s three-day-long Ice Cream Shop Operations 101 and its rigorous seven-day-long Ice Cream Short Course, considered the industry’s gold standard.

Still, Meyer says, even though she’d dreamed of her own place, she hadn’t fully committed to having her own establishment. She was enjoying success selling her ice cream, which she named Triple Panna (a reference to the triple servings of cream she usually orders with her gelato in Italy), at the Bronx Night Market and other New York pop-ups. Her father urged her to be more ambitious.

“His best advice was last year. People wanted me to do more pop-ups, and there are so many opportunities in New York. I thought I was just going to keep doing these markets. He asked me why and I said, ‘I need to test out the brand.’ He said, ‘You’re just doing them for fun. If you want to have a place, open a place and do not distract yourself with anything else.’”

After initially pushing back, because “pop-ups are just so fun,” Meyer relented.

“That was good advice. It’s all sort of under the same theme: Slow down to move faster. For me, it’s just easier to do, do, do, do, and not ask, ‘What is the concept and who is it for?’” she says. “I think I’ve been doing a much a better job this time around than I did with Umi Kitchen. In the startup world, either you’re playing it safe or it’s, ‘We’re going to expand. Make it big. Spend a lot of money. Break things. Go, go, go.’ I’m doing this the opposite way. I need to prove that one single Caffè Panna can be a delightful place to be.”

For his part, Danny Meyer says after giving advice, he moved out of Hallie’s way. “I love that I can say with a 1,000 percent straight face that Caffè Panna is entirely Hallie’s,” he says. “Almost every article about this place will say who Hallie’s dad is, but it’s really her project. She’s one of the most determined people I’ve ever met in my life. She’s only 26, but this is a compendium of so many aspects of her life’s experience, starting with persistence, to imagine it and pull the right team together. She’s been interested in community, food, team building, design and in love with Italy and with ice cream, and here it all is, coming together.”

While Danny Meyer has eschewed direct involvement, Audrey Meyer helped with some design decisions and last-minute troubleshooting, running to Fishs Eddy for dishes when the ones Hallie ordered weren’t delivered in time.

In the tradition of parents everywhere wanting their children to have an easier life, Audrey admits that she wasn’t sure she wanted Hallie to work in hospitality. “Hallie was always a great baker and a cook, but she was also really academic, and I thought she’s going to be a wonderful writer for a magazine or write books. When she was teaching in the Bronx, I thought maybe she’d become a teacher,” Meyer says. “But it’s funny, after Hallie got the [ice cream course] certificate from Penn State, she said, ‘You know what Mom, this piece of paper is worth more to me than the Yale Bachelor of Arts.’ She’s obsessed with ice cream, and she really has an entrepreneurial instinct.”

For Danny Meyer, who was 27 years old when he opened Union Square Cafe in 1985, Hallie’s debut brings back poignant memories and heals some old wounds, an example of how one successful generation can allow the next one to define their own success.

Speaking two days after Caffè Panna’s friends and family preview, Danny Meyer was melancholy about his own father, a St. Louis travel executive who also owned some restaurants. “One thing really struck me at Hallie’s opening. I remember at my own opening for Union Square Cafe, my father wasn’t present. That’s something that’s never left me, and I felt great that this was a really easy thing to celebrate with my daughter,” he says. “In the case of my own dad, he may have felt at some level that this was a little too close to what he was doing. That wasn’t lost on me. It felt great to put that behind me, by being for Hallie what I wished my dad could have been for me.”

I’ve been obsessed with ice cream pretty much my whole life.

At the opening, Hallie Meyer worked behind the counter, proffering the waffle cones she makes herself, topping them with praline pecan crunch, drizzles of caramel and panna in regular and local raspberry flavor.

Though she’s deeply serious about her business, Meyer sounds more like a gleeful child describing her creations, extolling the “cheesecake-y vibes” of her red flag flavor, a mix of strawberry swirl and graham cracker brittle, and the optical illusion of Café Bianco stracciatella, which looks like the standard Italian chocolate chip flavor but has a surprising kick of white coffee.

“I’ve been obsessed with ice cream pretty much my whole life. You can’t possibly be upset when you’re eating it, and everyone feels a connection to it,” she says, smiling. “I just love scooping ice cream.”