In its April-May 1992 issue Worth profiled budding entrepreneur Russell Simmons, who had just launched Rush Communications and had founded Def Jam Records almost a decade prior. Now credited with helping to introduce black culture to the mainstream, Simmons went on to become a hip-hop mogul with an estimated net worth of $340 million in 2016.

Russell Simmons embraces his multiline phone like a drowning man grasping a lifeline. Indeed, if the phone should ever go dead, Simmons would be lost. Simmons, 34, is head of Rush Communications, a year-old entertainment company nurtured on his rapid-fire talk and a talent for hype and image-making. His goal? To sell black culture to anyone who will listen.

So many people have listened since Simmons and a then-partner launched Def Jam Records nine years ago that the hydra-like Rush is today worth about $50 million, with gross revenues of $35 million. With Def Jam recording Public Enemy, LL Cool J and Third Bass, among others, and with six other labels, plus companies that manage producers and artists and develop film and television projects, Rush is the largest black-owned business in the entertainment industry.

Simmons’ goal? To sell black culture to anyone who will listen.

“Simmons gets maximum respect because he pioneered a whole movement, brought it into the mainstream,” says Jon Shecter of The Source, a magazine devoted to rap music. And through a joint venture with CBS, he’s got the clout to ask for the best deals and promotion.

Simmons’ phone rings: “How-ya-doin’-I’ll-call-you-from-the-car.” Slam. Smile.

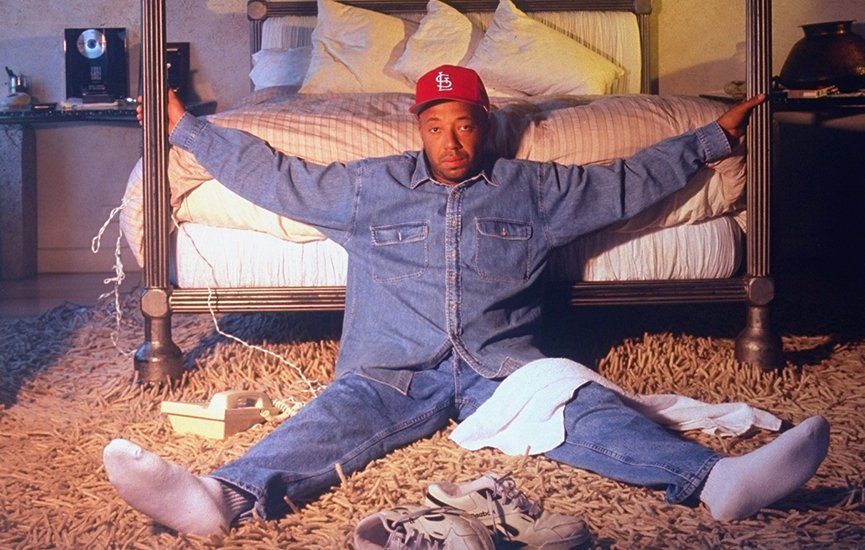

Simmons has the look of a late-night buddah, with three days’ stubble covering his round face. A sociology major who left City College of New York after his second year, he speaks in bursts of ack-ack fire, rarely completing a sentence.

“The market’s come to us,” Simmons says with pride.” We haven’t gone to them. Why? Because we don’t make records, music or television for black people, but for people who consume black culture.” Those consumers spent about $1.37 billion last year on the wide world of rap.

The phone again: “That’s very fly, baby. I’ll call you from the car.”

Simmons’ critics say he creates fantasies of black street life to satisfy a white taste for heightened urban realism. But he’s convinced there’s a historical value to rap: “N.W.A.’s Life in Compton is the only thing that will tell us in the year 2050 what growing up in the ghetto was like,” he contends.

He also upholds Public Enemy, which created a furor with its anti-Semetic and misogynist lyrics, for introducing Afrocentrism to black youth. “Public Enemy is singing about black power with pride.”

Next question?—Elizabeth Royte

Reprinted from the April-May 1992 issue of Worth.