In November 2002 Worth featured a profile on restaurateur and club owner Jimmy Rodriguez in which editor at large Nancy Holmes said: “A Puerto Rican kid from the Bronx who has conquered café society, Jimmy Rodriguez mixes up a cocktail of glamour, high energy and success that all New York wants to taste.” Although the former hot spots for which he became known in the 1990s and 2000s—including Jimmy’s Bronx Cafe and Jimmy’s Downtown—are now shuttered, Rodriguez continues to reinvent himself. When interviewed by NY Sports Day columnist Ray Negron in December 2016 about his latest venture, Jimmy’s NYC, Rodriguez said: “I wake up every day trying to be a bigger inspiration than I was yesterday and try to open up more doors for young men and women—not just Hispanic, but to show diversity. To show that [if] you believe it, you can achieve it.”

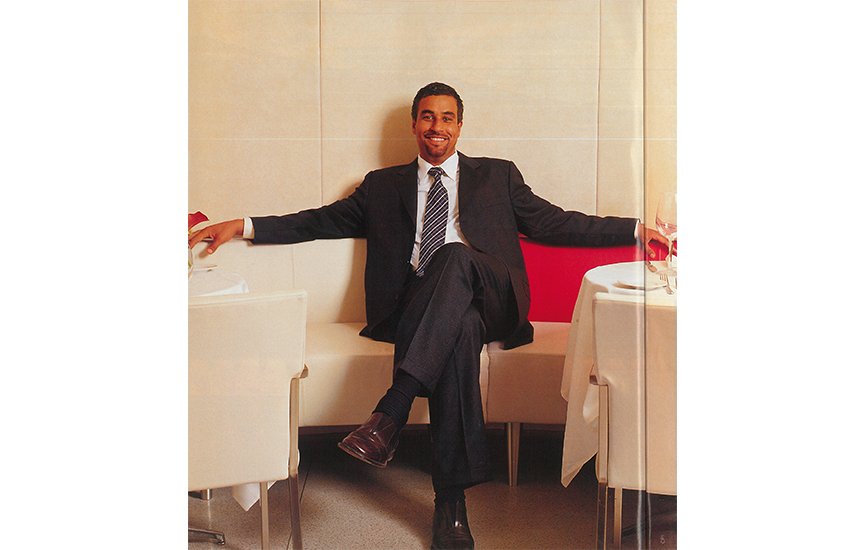

Seated on a narrow white leather banquette across from the 100-foot-long shiny red bar at Jimmy’s Downtown on East 57th Street in New York City, Jimmy Rodriguez Is keeping an eagle eye on the hustle and bustle going on at his newest venture, in Waspy Sutton Place. Tall and leaning-man handsome, with a faint air of Cesar Romero about him, Rodriguez is the city’s newest restaurant impresario and an unlikely success story for one of the richest zip codes in America. He is the hottest thing to happen since the glamour days of John Perona at El Morocco, Sherman Billingsley at the Stork Club, and Ian Schrager at Studio 54. All of them once ruled New York City’s restaurant, bar and nightclub scene. It’s Jimmy’s turn now.

Being hot is nothing new to him. His 40th birthday in September marked his 25th year in business, and his success and popularity have spread from the Bronx to Harlem to Manhattan. The question is: How has he achieved this kind of success when he started out with no money and no rich financial partners? Banks wouldn’t even consider loaning him money. So what is Rodriguez’s recipe for success?

“For years, people have said to me, ‘Why would you want to do a nutty thing like start a restaurant in the Bronx? Or ‘The place is jinxed’ or ‘It will never work,’” Rodriguez says, grinning his big smile as he rises to greet, bear hug, slap on the back, kiss or shake hands with Yankee baseball players, models, writers, Sutton Place socialites, actors, musicians or politicians—all of them wanting to let Rodriguez know that they are there, which is anywhere he is, in any one of his three high-octane restaurants.

Rodriguez opened Jimmy’s Bronx Café in 1992 in an abandoned Oldsmobile showroom. It remains the largest Latin restaurant, bar and dance venue in the country. Eight years later, he opened Jimmy’s Uptown in a once-derelict building in Harlem. And in May 2002, he ventured into the tony enclave of Sutton Place to open Jimmy’s Downtown. Asked why he would refer to East 57th Street as downtown, Rodriguez replies, “Honey, anything south of 96th Street is downtown to me.”

By any measure, Rodriguez is living proof that the American dream is alive and thriving. “I’m a Puerto Rican kid, born in the Bronx,” he explains. “My father was a fishmonger. When I was a teenager, the two of us sold fish, clams, shrimp and oysters from big vats beneath an overpass, summer and winter, rain or shine.” At the end of the day, they cooked up fish chowder from the leftovers and sold it to everyone going home on the Major Deegan Expressway. “It wasn’t pretty, but it was character building,” Rodriguez says.

At 17, he says, “I was making a couple thousand a week selling used cars… But I really wanted to open a restaurant with great Latin food where people could dance.”

Father and son lost touch for a while when “my father chose booze, women and gambling over me,” Rodriguez says. To make a living, Rodriguez took jobs washing dishes, driving a cab and buying and selling used cars. At 17, he says, “I was making a couple thousand a week selling used cars. I always wanted to be the best at everything I did, and I was. But what I really wanted to do was open a restaurant with great Latin food where people could dance.”

He had his eye on a possible location on Webster Avenue in the Bronx, a building that was in terrible shape and whose owner was desperate. Rodriguez saw his chance.

His first restaurant, Mariscos del Caribe, began to take shape. Rodriguez reunited with his father, who became his partner in that business. Although Rodriguez had no substantial investment capital beyond a few thousand dollars from his used-car sales, he did have equal measures of chutzpah and salesmanship. What others saw as an eyesore, Rodriguez saw as his future. “My buddies pitched in to help, painting and fixing up the place. My mother and some of her friends cooked. Even the musicians worked for tips at the start,” he says. It wasn’t long before Marisco del Caribe developed into a 60-seat song-and-dance spot with spicy food that was packed every night.

Then, as now, Rodriguez was leveraging his life every inch of the way, bartering and promising, never putting money aside, taking the profits from one place to put in to the next. He always made deep friendships; people liked him and believed in him, wanted to work with him or for him. Dominica Tejeda has worked for Rodriguez for 17 years as his manager at the Bronx Café. Linda Japngie, who once worked at La Caravelle, is now executive chef at Jimmy’s Downtown. Fiona Ruane has taken over for Japngie as executive chef in Harlem, and Brenda Hildenbrand, a slender blonde who is a dead ringer for the formidable C.Z. Guest, is the executive director at Jimmy’s Downtown. “I love the women who work for me,” Rodriguez says. “They are the best.”

In 1991, he spotted an abandoned 48,000-square-foot Oldsmobile showroom on West Fordham Road in the Bronx. The roof had fallen in, but it was here that the biggest risk of Rodriguez’s life was to pay off.

He stuck his neck way out and borrowed $1 million from a well-known Bronx “money lender,” who charges him 24 percent interest for his privilege. Jimmy’s Bronx Café was born as a sports bar and hangout for Rodriguez’s eclectic collection of baseball buddies, local politicos and musicians. The place was plastered with autographed baseball memorabilia. Immediately, it suffered a setback. As Rodriguez put the finishing touches on his opening-night party in the winter of 1992, New York City experienced the biggest blizzard of a decade. Nobody could get there, so nobody came. It was a crushing blow. Rodriguez was not only in a tough neighborhood, but he was in a tough business—70 percent of all new restaurants fail in their first five hears. “But nothing was going to stop me or kill my enthusiasm,” he says. “Once the bar got going—and it did—I knew it was going to be OK.”

Next, Rodriguez turned the basement into a nightclub with Latin music and called it El Diamante. In the spring, he put some tables and chairs outdoors in the empty parking lot and started a summer café called the Patio. That worked too. He was bankable now. He refinanced Jimmy’s Bronx Café with an SBA loan and paid off the money lender in the Bronx.

In 1999, Rodriguez found yet another fixer-upper on Seventh Avenue and 131st Street in Harlem, near housing projects. “Jimmy has always had great intuition and been extremely clever about real estate,” says Lawrence Graham, whom Rodriguez refers to as his CFO. Rodriguez bought the building by negotiating a mortgage from the seller, and in January 2000 he opened his next restaurant there, called Jimmy’s Uptown. Ilan Waisbrod, an architect and another Jimmy believer, redesigned the interior, agreeing to be paid in full when the restaurant opened. The Shiloh Baptist Church is across the street, and Rodriguez wisely started serving gospel brunches on Sundays. “Jimmy would say, ‘Come have some cheese biscuits and gravy and soul food,’” Graham recalls. “He’s a pied piper. Everyone came.”

Although Rodriguez was always willing to take crazy risks that no one else would when he opened in Harlem, he realized that even he couldn’t do everything himself; he had to learn to delegate. That’s where Graham came in to keep track of it all. Rodriguez had no partners, and his holdings comprise numerous individual corporations. Asked if he’s ever had a failure Rodriguez confesses to a few small ones. “A little place in a shopping mall someplace out in New Jersey,” he says. “City boys don’t do towns.”

The society columns reported that his guests included half of the socially prominent boldfaced names in New York City.

In 2001 Rodriguez decided to open another restaurant, focusing this time farther south, in Sutton Place. The residents of the stuffy neighborhood were up in arms, horrified at the thought of a hangout for hipsters in their midst. Word went around that drugs, drunks and loud music were going to rock the neighborhood—that is, until a preopening birthday party in April 2002 for popular jeweler Kenneth Jay Lane brought Jimmy’s Downtown coveted press coverage. The society columns reported that his guests included Pat Buckley, the Earl and Countess of Albemarle, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Nan Kempner and half of the other socially prominent boldfaced names in New York City.

Rodriguez knows how to cater to his crowd. “Come on in and have a drink,” he says to everyone passing by. A signature Jimmy touch is his practice of putting out bowls of water and dog biscuits every day for man’s best friends in Sutton Place. Also appealing is the dress code. No one is admitted to his restaurants without being well dressed, although ties are not obligatory. Rodriguez himself is a fan of Armani and Dolce & Gabbana suits and Ascot Chang custom-made shirts.

Jimmy’s Downtown is not a project that involved being bandaged or fixed up in the manner of the Bronx and Harlem properties. It took considerable money to turn the Sutton Place spot into the stunning and expensive bar and dining room it is now. Graham and Rodriguez are reluctant to say more than that “it cost about $1 million” to achieve, and they do not volunteer where that million came from. Rodriguez does say that all three of his places make money. His payroll includes 260 employees. He supports a wife, from whom he is separated, and three children. He drives a white convertible Jaguar and a Cadillac Escalade and is known as both a reliable friend and a man with a somewhat bad-boy, raffish image. On seeing Rodriguez dance, author Jay McInerney once wrote, “It’s mainly about the hips. Jimmy reminds me of one of those machines they use to mix paint at Home Depot.”

And music is what matters, Rodriguez says. “I would never have a place that plays the same beat hour after hour. It’s boring. We change every 20 minutes—everything from merengue to jazz to salsa to Sinatra—so the tempo is always fresh,” he says.

Rodriguez thrives on a regular change in tempo. His close friends implore him to not spread himself too thin, but he is deaf to their pleas. In January, he plans to open a new place in Harlem called Sugar Hill. “It will have good Latin food,” he says. “So come on up and have dinner with me. And bring all your friends.”

Reprinted from the November 2002 issue of Worth.