To mark 2017 New York Fashion Week, we’re taking a look back at Steve Salerno’s December 1998-January 1999 profile of Donna Karan, who stepped down from her eponymous fashion house in 2015. The piece highlighted how Karan, who founded her label in 1985, reaped the profits of licensing fees even as the stock of her company plummeted. Salerno’s piece is a cautionary tale for investors then and now.

Things are not supposed to work out like this in the world of high finance. The deck—even the game itself—is supposed to be stacked in Wall Street’s favor. How is it, then, that a Seventh Avenue fashion designer—one who is famously inept with numbers—was able to tilt the process of capital formation almost entirely to her own benefit? For that is what Donna Karan has done, despite a swell of unfavorable publicity to the contrary. Investors in her company may not like it, but they certainly share in the blame.

Virtually every recent news story about Karan has, in one way or another, faulted her for chaotic, bar-no-expense business practices that have driven the price of Donna Karan International stock from its 1996 initial-public-offering price of $24 a share to its current level of around $7. There have also been accusations in shareholder lawsuits that Karan’s financial team misled investors about the health of the company.

It is certainly true that DKI has yet to live up to the promising future depicted in the offering documents prepared for the IPO. Annual profits have dwindled from the $56.1 million the company reported for 1995 to an expected $12 million or so this year. The current gibe on the Street is that the stock-market symbol “DK” really stands for “Don’t Know.” Available data about the company has often been either too scarce or too inscrutable to support intelligent trading. Yet the full story of Donna Karan and Wall Street is far more complex than a simple case of unmet hype. Among other things, it’s an example of the love-hate relationship that often develops between the investors and the players in supposedly glamorous businesses.

Few, of course, dispute Karan’s fashion sense. This notwithstanding her early departure from New York’s Parsons School of Design and her dismissal from her first job, with Anne Klein. Her genius has always been her keen understanding of the tastes and needs of upscale career women. It was Karan who dreamed up the landmark notion of “seven easy pieces”: a collection of bodysuits, dresses, skirts, blouses, jackets, pants and accessories that, when layered in all their possible permutations, produced “a consistent but varied high fashion look,” as her publicity material put it.

In 1989, Karan pioneered what was to become her best-selling line, an assortment of “bridge” apparel (that is, bridging the gap between designer sportswear and moderately priced clothes), under the trademark DKNY. In so doing, Karan displayed a unequaled grasp of what Hollywood calls high concept. Says Jeff Haims, one of her key designers at the time, “She looked at me and said just two words: ‘Fashion Gap.’ And we both just knew.” The years 1991 and 1992 saw the debut, respectively, of Karan’s designer and bridge lines for men. After that, she introduced fragrances for both genders and trotted out a line of cosmetics. By 1995, the company she had started from scratch 11 years earlier was generating annual revenue of $510 million—not too shabby for someone who supposedly can’t manage a business.

Then came 1996, the year of Karan’s now infamous sale of stock to the public. Throughout the 1990s, IPOs had increasingly come to be seen by investors as a device for turning an easy profit—and by the owners of private companies as a way to cash in on what they had built. In a period when the stock market itself could do no wrong, it had become almost commonplace for newly issued shares to skyrocket the moment they were offered for sale.

Actually, despite the inclusion of the word “public” in their name, these stock offerings were often out of bounds to all but the most well-connected investors, such as large mutual funds, institutional equity managers, and well-heeled private investors. This served only to increase their mystique and their appeal.

Somehow lost amid this IPO mania was any ongoing sense of the fundamental dynamic that underlies all such flotations—a conflict between buyer and seller. Most investors are quite familiar with the idea that a corporation’s top brass is supposed to work in the best interests of shareholders. In an IPO, however, the ownership itself is in the middle of a transition. New investors want to be able to acquire the shares of a promising company at the lowest possible price. The owners, on the other hand, want to get as much as possible for their stake. An IPO, in other words, pits outsiders against insiders.

Karan (who declined to be interviewed for this story) hardly seems a formidable opponent in this type of situation. Her expertise, after all, is in high fashion, not high finance. She’s also well known as mathematically challenged. Says a former colleague: “Donna is the kind of person who, if you told her a jacket will be delivered on 9/1, she’d give you a blank stare. You have to tell her ‘September first.’ Anything to do with numbers she just doesn’t get.”

During investor road shows prior to the IPO, Karan had to be coached by her staff on the meaning of such simple abbreviations as “EPS” and “ROI.” Even then, she often shied from answering basic questions about the business, preferring instead to model (in a routine she had worked up with her personal trainer) favorite pieces from her latest high-end collection: “The black-leather coat for damp days in London, the acid-green jacket to give Paris a lift, the white-linen jacket to blend into Beverly Hills,” as she explained in a 1996 article in Vogue. In that article, published as a diary of her experiences, she added that people had warned her that the IPO would be “the worst experience of my life.”

It wasn’t as though there were no important business issues to be addressed. The company was, after all, little changed from the one that had sought to go public three years earlier—only to retreat. In November 1993, Karan’s company had backed off from a planned $160 million offering amid speculation that management was shaky and that turbulent times lay ahead. Selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses, which analysts had balked at as excessively high in 1993, had still not been tamed by 1996. Product lines in stores or in final-phase development at the time of the first offering, such as the much-ballyhooed beauty division, had “not yet been profitable,” according to the 1996 prospectus. In 1994, the New York Times published an article in which Karan’s finances were described as “spinning out of control.” Corporate Financing Week then recounted the company’s difficulties in arranging a $75 million public-debt offering.

Finally, the fashion business itself is notorious for its cycles of feast and famine. Any Seventh Avenue habitué will tell you that for every Calvin Klein that manages to stay relevant there’s a Gloria Vanderbilt or Isaac Mizrahi who falls out of favor. Mizrahi—once, ironically, dubbed the “heir apparent to Donna Karan”—shut his doors in October. And then there is the spending. It was not unusual for Karan to charter a jet because she was late for an appointment, to pay a lavish salary to a top assistant, or to dispatch her corporate “director of inspiration” to the African veld in search of tribal weavings.

These question marks were never deep secrets. But perhaps less well known, at least outside her circle of acquaintances, was Donna Karan’s second particular genius: She’s extremely adept at getting what she wants. Says Anne Taylor-Davis, president of Nautica’s in-house PR wing, “Donna is a lovely person. But would she keep the designers up all night before a show? Yes. And then would she rip up the show at the last minute anyway? Yes.”

Karan routinely sent back expensive commissioned products for 11th-hour tweaking, creating havoc with delivery schedules and retail buyers’ best-laid plans. “She once walked in and announced, ‘I want the perfect blue blazer,’” recalls Haims. “Well, we must’ve redone that blazer 100 times in the next eight weeks. When Donna makes up her mind, ‘no’ is not a word she understands.” No one knows this better than Stephen Ruzow, her chief operating officer between 1989 and mid-1997. According to insiders, Karan’s relationship with Ruzow, a former president of apparel giant Warnaco, fell into a chronic pattern that went as follows:

Karan: “I’m going to spend x amount on such and such.”

Ruzow: “You can’t do that. It’s not in the budget.”

Karan: “Oh, yes I can.”

And that was that. “I wasn’t empowered,” concedes Ruzow. “I was supposed to be curtailing expenses, but I reported to Donna.” Karan was chairman, chief executive and chief designer at DKI.

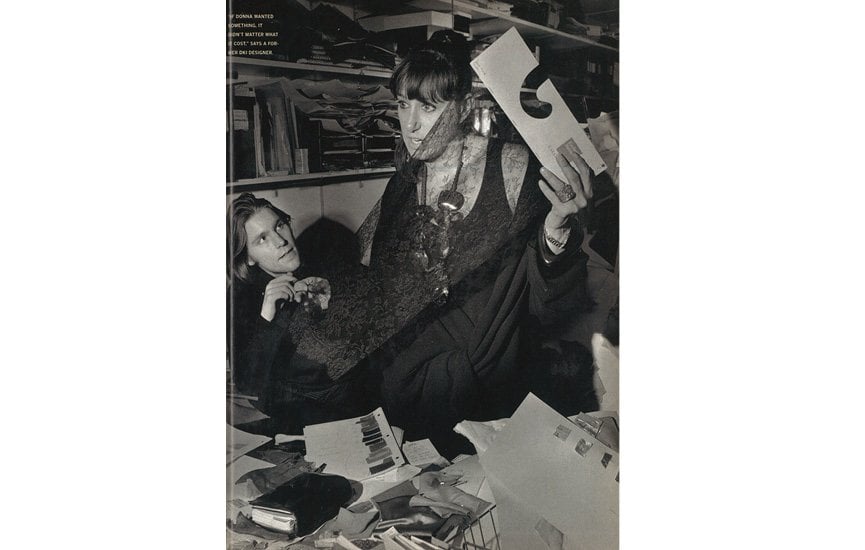

Karan’s truculence may not have been well known on Wall Street prior to 1996, but it was certainly no secret on Seventh Avenue. “If Donna wanted something,” says Haims, “it didn’t matter what it cost. That was how it was going to be.” An unapologetic perfectionist—at least in the design stage—Karan focused her efforts on creating only the most opulent products and showcasing them in commensurate style. She liked to work in cashmere and such, which she then draped on the lithe frames of the top supermodels: If Donna wanted Cindy or Claudia, no less than Cindy or Claudia would do.

This approach, of course, is partly what enabled Karan to rise to the pinnacle of a cut-throat industry. Persuading her to change would be a bit like trying to tell Steven Spielberg to stop shooting extra rolls of film. Perhaps, then, the question investors should have been asking in 1996 was not whether Donna Karan was ready for Wall Street, but whether Wall Street was adequately prepared to do business with someone like Donna Karan.

The question in 1996 was not whether Donna Karan was ready for Wall Street, but whether Wall Street was adequately prepared to do business with someone like Donna Karan.

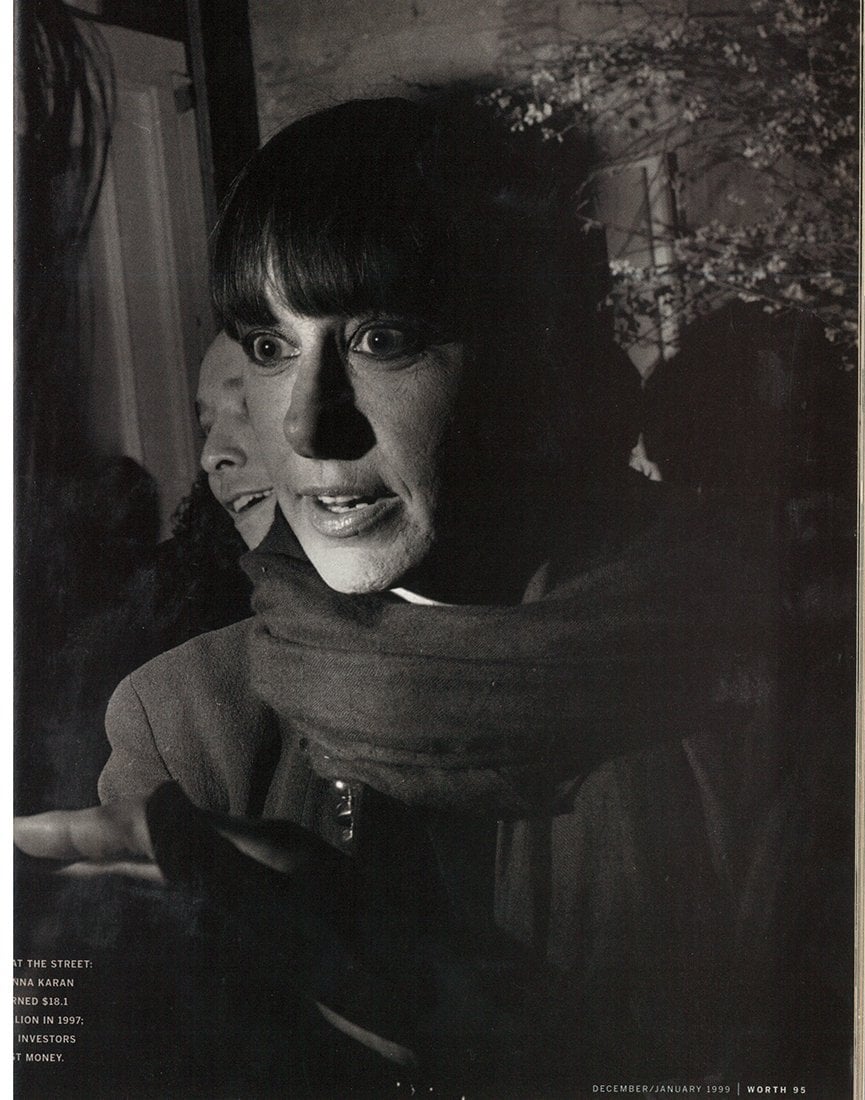

Beat the Street: Donna Karan earned $18.1 million in 1997; DKI investors lost money. Photo by Larry Fink

Beat the Street: Donna Karan earned $18.1 million in 1997; DKI investors lost money. Photo by Larry Fink

On Friday, June 28, 1996, Donna Karan International was finally ready to go public—this time for real. The company had actually planned to open the selling at a price of $21 or $22 a share. But demand for DKI stock was so strong that Morgan Stanley, as chief underwriter, suggested bumping the price up to $24. That morning Donna Karan herself rang the opening bell on the New York Stock Exchange.

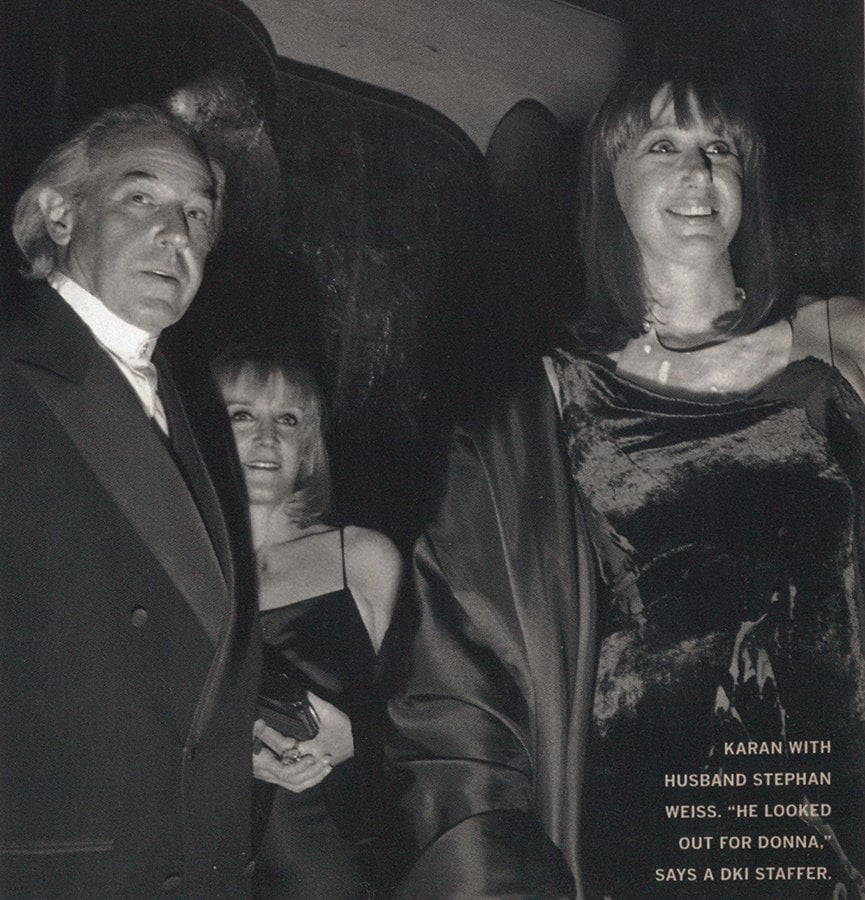

DKI’s new shares soared as high as $30 on that frenzied first day before finally settling at $28. That was roughly 28 times Morgan Stanley’s estimate of 1996 per-share earnings—the sort of price-to-earnings multiple commanded at the time by genuine money machines like Intel and Microsoft. In total, investors bought 10.75 million DKI shares, representing 51.4 percent ownership. Of the $236 million raised, Karan and her husband, Stephan Weiss, DKI’s vice-chairman, split $116 million with the Takihyo Group, one of the designer’s early angels. The rest was earmarked for “general corporate purposes” and for paying down debt. Karan and Weiss retained 24.3 percent of the company, as did Takihyo Group, a partnership consisting of Tomio Taki and Frank Mori.

Overall, the session went so well that Ryan Jacob, then research director at IPO Value Monitor, was moved to gush, “Having an IPO as successful as a Donna Karan portends well for companies looking to come public.”

Most of the early shares were snapped up by large institution—presumably favored customers of underwriters Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Smith Barney, and Bear Stearns. David Pearl, manager of the Landmark Small Cap Equity Fund, was among those who were favorably disposed toward the stock. “If you believe her brand is going to do well, this is a good company. The revenue is growing, and they have a lot of new products,” he told a wire service the day of the IPO. Pearl, however, was personally fortunate: He lacked the connections needed to actually buy any of the newly issued shares for his fund.

Not everyone thought DKI was a bargain. David Menlow of IPO Financial Network told the New York Times, “My question is whether or not Donna Karan’s ego is going to get in the way of this. Certainly I view the pending offering with a jaundiced eye.”

The IPO was certainly a fabulous deal for Karan—in a way that many investors apparently failed to realize. A highly unusual feature was an arrangement that allocated $5 million of the proceeds to a shell corporation wholly owned by Karan and Weiss. This shell corporation, named Gabrielle Studio after Karan’s daughter, was, in turn, granted exclusive rights to the trademarks “Donna Karan,” “DKNY,” “DK,” and “Donna Karan New York.” A 318-word clause in the offering prospectus stipulated various royalties and fees that Gabrielle Studio would receive. “Nobody thought this clause would get through,” recalls a DKI insider. “I was sure Morgan Stanley would take it out. But they didn’t.” (DKI’s chief contact at Morgan Stanley at that time, Dewey Shay, went to work in Karan’s company some months after the IPO. He has since left DKI. Calls to his home on Long Island weren’t returned.)

It’s unclear exactly who thought up the idea for the Gabrielle clause. Some insiders say it was Donna herself; others say it was her husband. Weiss, a sculptor, frequently got involved in company negotiations and was famous for demanding unreasonably favorable terms. “He looked out for Donna,” recalls one DKI staffer. “He made sure she came out of everything whole.”

By stripping the company of its most valuable assets, the Gabrielle clause should have raised serious doubts among potential investors. But it became an issue only later, as DKI’s fortunes began to reverse. A bright spot in the aftermath of the public offering was the expected consummation of a long-term jeanswear license with Designer Holdings. This was welcome news because the deal was sealed with a much-needed $6 million up-front payment. More important, it was Designer Holdings that had successfully boosted annual sales of Calvin Klein jeans to $640 million from $120 million. If it had worked for Calvin, might it not work for Donna?

The point became moot on March 4, 1997, when DKI and Designer Holdings annulled the contract. Ruzow explains, “The product Designer Holdings was going to be able to offer was strictly limited so as not to cannibalize the rest of our line. But they felt that when the time came, despite what the contract said, we’d give ’em what they wanted. Well, we didn’t.”

Arnold Simon, then chief executive of Designer Holdings, groused that it was Karan who “didn’t understand the agreement.” DKI refunded Designer Holdings’ money—not just the $6 million advance but other royalties and fees totaling $10.5 million. Analysts and shareholders alike were aghast. The company had to restate its 1996 third-quarter earnings. Alan Millstein, owner of Fashion Network, a consulting firm, opined that Karan had revealed herself as a “horse’s ass when it comes to running a business.”

Karan, meanwhile, was proceeding with an expansion plan that outstripped the company’s financial and management resources. She unveiled new retail outlets, overspent her ad budget by $5 million to fund a campaign featuring actors Bruce Willis and Demi Moore, and segmented her most successful DKNY division into five lines, with a dedicated staff for each. One line, D, got its own fashion shows at about $50,000 a pop. Corporate expenses rose rapidly even as sales slowed. Quality control became another headache: Buttons were falling off $1,500 jackets. In May 1997, while publicly traded fashion companies like Gucci Group, Nautica Enterprises, Liz Claiborne and Tommy Hilfiger were reaping handsome profits, DKI’s first-quarter results came in, and they were chilling: Earnings had fallen to $482,000 from $13.5 million for the same quarter the previous year.

By now, most DKI investors were furious. The stock had fallen to $11 a share. Fashion writers were devoting as much energy to tracking the company as an investment as they were to reviewing its new fall lines. Yet some Street types apparently still couldn’t get the glitter out of their eyes; despite the well-publicized turmoil at DKI over the previous six months, the dour first-quarter earnings were fully 80 percent lower than estimates from several prominent forecasters.

Fashion writers were devoting as much energy to tracking the company as an investment as they were to reviewing its new fall lines.

Karan with husband Stephan Weiss. “He looked out for Donna,” says a DKI staffer. Photo by Larry Fink

Karan with husband Stephan Weiss. “He looked out for Donna,” says a DKI staffer. Photo by Larry Fink

Shareholders became particularly irked once they took time to learn more about the Gabrielle Studio license. The arrangement entitled Karan and Weiss to receive sliding-scale royalties: 1.75 percent of the first $250 million of net sales a year, rising to 3.5 percent of sales exceeding $1.5 billion. The resulting payments—the only known disbursements of their kind among Seventh Avenue public companies—average about 3 percent at the moment. They totaled $9.3 million in 1996 and $17 million last year. Including the Gabrielle royalties, Donna Karan’s 1997 compensation of $18.1 million was, by far, the most paid to any Seventh Avenue executive. (Number two in 1997 was Ralph Lauren at $14.7 million, followed by Tommy Hilfiger at $10.4 million.)

Still, it wasn’t as though DKI’s IPO prospectus had kept this arrangement—or its potential impact on the bottom line—a secret. For example, it specifically warned that, had the agreement been in effect throughout 1995, Gabrielle Studio would have received $12.8 million.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the clause is that Karan’s percentage comes off the top. Suppose, for example, the company were to license the Donna Karan trademark to a hatmaker in return for 10 percent of the hatmaker’s Donna Karan sales. Gabrielle Studio effectively would get not 3 percent of what the hatmaker pays to DKI but rather three of the ten percentage points, or 30 percent of the total royalties received. The remaining seven percentage points would go to the company — but, of course, public shareholders own only 51.4 percent of the stock, which effectively further halves their take.

John Idol, who took over as CEO at DKI in July 1997, says that the Gabrielle deal “is a contractual commitment the company made, and we will honor our contractual agreements.” Board member William Benedetto is less guarded: “That’s what shareholders bought. It was right there. If they didn’t notice it, they have no one to blame but themselves.”

“That’s what shareholders bought. It was right there. If they didn’t notice it, they have no one to blame but themselves.”—a DKI board member

The nation’s premier specialists in stockholder class-action lawsuits, Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Lerach, has had little success proving otherwise. In a consolidated complaint representing three federal actions filed on behalf of DKI shareholders in the summer of 1997, Milberg Weiss alleged that Karan’s financial gurus spent the interim between the 1993 and 1996 IPO efforts dressing up a company whose innards were suspect. But Federal judge Carol Bagley Amon determined the complaint lacked hard evidence and dismissed the case last August. Milberg Weiss is considering re-filing its suit.

Idol, meanwhile, is well along in the omnibus turnaround plan he devised shortly after his arrival. To shrink bloated inventories, he has slashed the number of high-end styles and introduced new staple items apt to move more consistently. He dropped the price points on the best-selling DKNY line 20 percent for women and 30 percent for men, eliminated 8 percent of Karan’s in-store displays and consolidated DKI’s 13 divisions to six. And he cleaned house. Gone are Ruzow, George Ackerman (head of DKNY for men), Mary Wang (DKNY for women), Linda Beauchamp (top-line menswear) and production chief Louis Praino.

The personnel moves in particular have earned Idol considerable enmity on Seventh Avenue. But he contends he had little choice: “The product lines had stopped performing. A lot of the price-value relationships were way out of balance. I can’t sit here and tell you there was one area of the company more out of control than the other.”

Idol predicts his fixes will save the company $40 million annually in expenses while boosting wholesale revenue to $1.5 billion from $850 million by the year 2000. Unlike Ruzow, the strong-willed Idol has been given the clout to say no to Karan on spending—the one concession she finally made in recognition of DKI’s status as a public company. According to some insiders, in fact, Idol’s arrival represented the first time Karan has had to duel with an ego as large as her own.

Then again, he has also been making her even richer. Idol’s specialty at his previous employer, Polo Ralph Lauren, was licensing—a skill he has applied with a vengeance at DKI. He got Estée Lauder to take over the troubled DKI beauty business. Liz Claiborne, meanwhile, landed the jeans contract as well as rights to several ancillary lines of apparel; DKI stands to reap $152 million in royalties over the 15-year life of this deal alone. Then again, under the Gabrielle clause, an estimated $53 million of that will go directly to Karan and Weiss.

The danger now for DKI’s public shareholders is that the various licensing arrangements—Idol has inked seven just in this year—will limit the potential of the company, or worse. Faye Landes, a highly regarded retail analyst at Salomon Smith Barney, worries that the jeans license might mean that consumers will buy from Claiborne items they once would have bought directly from DKI, with Claiborne pocketing the lion’s share of profits. “There is a finite amount of retail space and a finite amount of closet space,” says Landes. “The question is, how large and strong a core business can DKI maintain?”

DKI’s gross margins have already slipped. Says one former staffer, “I don’t care how much you sell; if you sell it at 75 percent off, you’ve lost money.”

Former production chief Praino further wonders whether Idol’s low-end, high-volume strategy is staining brand image: “I mean, he’s selling to Sam’s Club,” says Praino.

Bottom line, says Ackerman, the former chief of DKNY for men, “It’s a business that never should’ve been public. The company had no ‘basics,’ no replenishment business. Didn’t then, doesn’t now. We never had a white shirt that would last for 10 years. The Polo button-down has run since 1967. Our shirt would run for 18 months, and then we had to invent another one.”

And yet, all that said, the numbers are looking somewhat better. After failing to meet even the most dismal earnings forecasts in 1997, the company rebounded in the first half of 1998. It posted $306 million in net revenue—$36 million better than the same period in 1997—while impressively cutting SG&A expenses to $73.9 million from $92 million. Its first-half net loss of $4.2 million was significantly below the $13.8 million deficit it recorded during the first six months of last year. Analysts now expect the company to earn between 70 cents and a dollar a share in 1999.

At its current price of around $7 a share, the stock of DKI may have finally found something like a reasonable level, though it was clearly never worth $28, and its exact value remains controversial; several Street rating services now label DKI a “moderate buy.” In the end, the appeal of Donna Karan’s stock, much like that of her clothes, has always resided in the eye of the beholder. If nothing else, investors now ought to have a better grasp of who they’re dealing with and what they actually own—or, more crucially, what they don’t own. Ultimately, a turnaround in the stock would also benefit Karan herself, making her an even bigger winner than she already is.

Reprinted from the December-January 1999 issue of Worth