David Rubenstein has forged a truly unusual career for himself. After a stint working on domestic policy in Jimmy Carter’s White House, Rubenstein cofounded the Washington, D.C.-based Carlyle Group and helped build the private equity firm into an industry giant with some $370 billion under management.

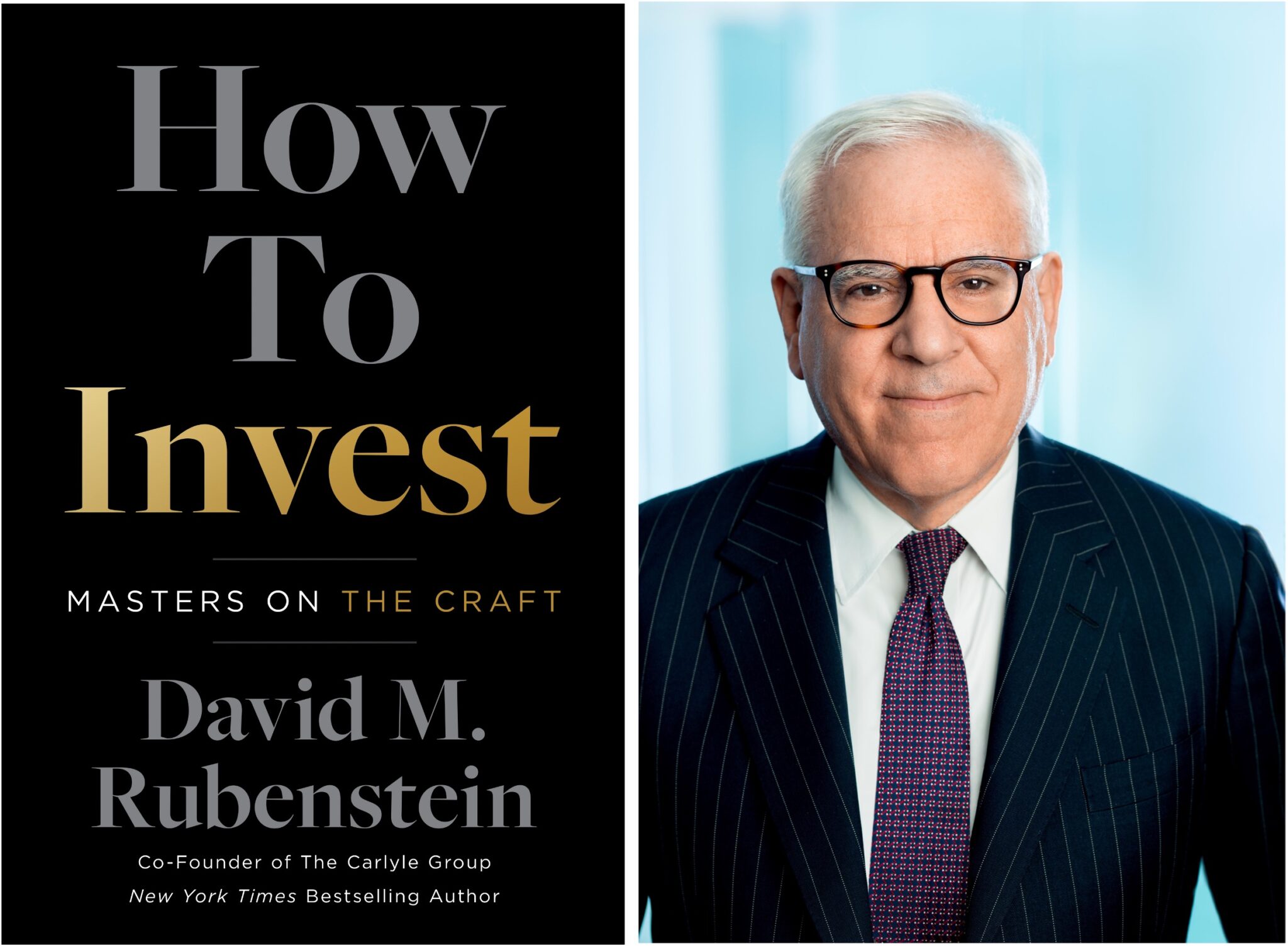

Rubenstein, now 73, has in recent years moved into the media business: He is the host of two interview shows on Bloomberg TV and PBS, a podcast, and recently authored his fourth book, How to Invest—Masters on the Craft, a series of conversations with many of finance’s most successful investors.

A student of American history—his first book was called The American Story: Conversations with Master Historians—Rubenstein has given millions of dollars to projects such as the restoration or repair of the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Jefferson Memorial, all in Washington, D.C. Rubenstein, whose wealth is estimated to be over $3 billion, is a signer of the Giving Pledge, committing to give away the majority of his wealth to philanthropic causes.

Q: David, after many years in which you were best known as a cofounder and cochairman of Carlyle Group, you seem to have created a new career for yourself as a media personality. How do you divide your time now?

A: Well, I’m still the cochairman of Carlyle and its biggest shareholder, and am still actively involved. And I have a family investment office called Declaration Partners. So, I’m still spending most of my time in the investment world. I also chair about seven nonprofit boards. That takes time. I do a couple of television shows—I have a new tv special coming out second quarter on PBS. I’m trying to juggle a lot of things. I’m not good at saying no.

Is that stressful?

I enjoy it. I just wish I was younger and had more time.

Your book is a series of conversations with great investors about how they do what they do, but it sometimes feels like a defense of the investment business. Did you feel there’s a need to do that?

I don’t know that I need to defend investors, but I do feel that there’s a need to defend capitalism. Very few people are willing to say publicly, “I’m a capitalist.” It’s an interesting word situation. How many Democratic politicians do you hear say, “I’m a liberal”? They say, I’m a progressive. Does anyone say, I want to get a bridge funded in my district, it’s pork barrel? No, they call it infrastructure. People don’t want to say, I’m in private equity. They say I have a family office.

Certain words have good connotations—or not. Take your publication, Worth. People pick it up because “worth” implies money, and people want to learn more about money. If you called your magazine Poverty, how many people would pick it up?

So “capitalist” has become a bad word?

“Capitalist” has become a word that very few people like to use, but capitalists and investors do good things for society. Investors should not be looked at as greedy people trying to accumulate money, but as people who build businesses that employ people and who give money away to philanthropic things. Instead, people who have earned wealth have been under some attack, particularly when they get involved in philanthropy.

How so?

There is a sentiment now that says that wealthy people shouldn’t be able to give their money away—we should tax it instead. Take a look at some of the best-known philanthropists in our country. They’re heavily criticized for doing what they do. Bill Gates is criticized for giving away money in ways that the government would not do.

You also hear the argument that investors should do things with their money that aid people more directly—instead of buying Twitter, for example, Elon Musk could have used those billions to feed the world for a day.

Wealth, to some extent, is always under attack. Nobody’s ever loved wealth that other people have. And people in the U.S. have gotten extremely wealthy during the last couple decades—maybe they do have too much money. That doesn’t mean we should throw the baby out with the bathwater. We should recognize that people who have made money and can give it away can do some useful things for society.

Your book contains rules and advice on investing, but the people with whom you spoke—investors such as Ray Dalio, John Paulson, Sam Zell—are exceptional figures. Is the ability to be a great investor really something you can learn, or is it something in your DNA?

If your mother and father were Olympic athletes, you might be a good athlete, but most great athletes do not produce great athletic children. The same is true with investors. Most great investors are not famous for having produced children who are great investors. So there are some advantages to having parents who are great investors, but to get to the top requires drive and a certain set of luck and skill.

You also argue that most great investors are not rags-to-riches, “Horatio Alger” types, but come from middle-class families led by happily married parents.

The Horatio Alger types tend to work their way up from low economic means and build companies, but not have the financial and intellectual discipline to be an investor. Not all the Horatio Alger types have great educations or math skills, and having an education and math skill helps in the investing world.

But the experience of these billionaire investors is so singular—do they really have lessons for the rest of us? Isn’t that like thinking that if you practice enough, you can do what LeBron James does, when you almost certainly can’t?

There’s always a risk of canonizing these folk, but society does benefit by having role models and people you can look up to and aspire to be. It used to be political leaders you would look up to, but we look to other places for role models now—athletic success, cultural success, financial. And maybe we make those people greater than they are. I have met many famous people over the years, and many are very, very impressive, but none are perfect. We all have flaws.

Speaking of famous people with flaws…you’ve contributed millions of dollars to historical restoration projects involving the Founding Fathers. Those colonial-era figures have been under attack in recent years for their involvement in slavery. How do you feel about efforts to tear down their legacies, both cultural and physical?

When I went through grade school, you read about George Washington and how great he was. You weren’t taught that he owned a lot of slaves, and that’s not something we’d consider to be a good thing today. The way I look at it is that it’s not a good thing to have slaves, but you can’t throw out everything that a person did that’s good. Some people say we should tear down the Washington Monument. Many people suggested we tear down the Jefferson Memorial. But those monuments were not erected to promote the idea of slavery as a good thing. In the early part of the 20th century, when we began erecting statues of Robert E. Lee, it was to promote the idea that slavery or racial segregation were not such bad things.

So remembering historical figures for their beneficial legacies is okay, but remembering them to promote reactionary ideas is not.

We have a thing called Stone Mountain in Georgia, and it has carved into it three famous Confederates: Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee. It was a way to remind people of the South and what’s called the “lost cause”—the idea that [white Americans] had a certain way of life and were trying to protect state’s rights. That was carved in 1972, and Spiro Agnew showed up for the dedication—the vice president of the United States. We’ve come a long way since then.

Let’s talk about your dual careers as an investor and interviewer. What do they have in common?

Intellectual curiosity. If a good investor has a really interesting mind, they want to know everything. You’re always asking questions, trying to get more information, to see if you have the best information. An interviewer has a lot of intellectual curiosity

Back in August, you interviewed Sam Bankman-Fried, the CEO of crypto exchange company FTX, for The David Rubenstein Show: Peer-to-Peer Conversations on Bloomberg TV. FTX has now imploded and Bankman-Fried has resigned amid allegations that he was using customer funds to prop up both FTX and his other business, Alameda Research. Is there anything now that you wish you’d asked him then?

I didn’t see red flags. He seemed to be a very young, idealistic person. He had an unusual way of dressing—the tennis shoes, shorts and t-shirt, the unkempt hair. I wasn’t smart enough to say, “Are you improperly using any of this money that comes in?” I just didn’t have that foresight. Nobody else did either.

How could so many intelligent people miss that there was something deeply wrong there?

I think there’s a general view that there’s always going to be some smart people that discover something great and will be the next Bill Gates or Steve Jobs, and when these people come along there’s a tendency to accept the idea that they are smarter than us.

You had a chance to invest in FTX but chose not to.

I don’t want to claim credit for it. My family office was invited to invest in the last round of FTX [in September] at a $32 billion valuation— that was the round when he raised roughly $250 million. My family office has a team that does investments in this area, and they looked at it and they killed it. They couldn’t understand where the money was going. They just didn’t understand the relationship between Alameda and FTX. They didn’t even think it was worth bringing to my attention.

When you interview people in finance and business and philanthropy, you’re a peer in those communities, which is unusual for an interviewer. The only other person I know who does that is Laurene Powell Jobs. Does that status help the people you’re interviewing feel more comfortable with you?

I interviewed Laurene Powell Jobs. She’s very cautious. Very cautious. I thought it went okay. I do know the investment world and the business world, and I try to ask the questions that many people might be afraid to ask or seem offbeat. I like to ask people, Did your parents live to see your success? Things like that to get people to open up. I’m probably not the toughest interviewer in the world.

Finally, David, you write in the book that great investors defy conventional wisdom. What’s the conventional wisdom on investing in the markets right now, and how are great investors defying it?

The conventional wisdom is we’re going to have a modest recession, and the conventional way to deal with that for most people is to stay out of the markets. The great investors are now moving into the markets and buying things at relatively attractive prices. Trying to buy at the bottom of the market is a fool’s errand. The smarter move is to start buying things at discounts. Even if they go down another 10 or 15 percent, if they’re good assets, they’ll rebound.