I don’t know what you keep in your basement, but now I know what Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts keeps in its storerooms.

It’s a couple of dozen paintings by Claude Monet, which are joining the 10-15 Monets typically on display in the museum’s Impressionist galleries, for an exhibition of the MFA’s complete Monet holdings, available for your enjoyment through March 31.

Monet, whose art has graced the walls of a million college dorm bedrooms, gave the name to the Impressionist movement in Paris in the late 19th century when a young group of rebel artists banded together to stick it to the traditional, boring landscapes that were the only acceptable paintings to purchase for the bourgeoisie.

The goal of the Impressionists—whose name specifically comes from a London painting of Monet’s, Impression: Sunrise, a view of the Thames—was to paint the way light actually hits things instead of creating the stultifyingly boring classical landscapes that hung in the apartments of the better class of Parisians.

The rebels, who included Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Mary Cassatt, Georges Seurat, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Gauguin, Auguste Rodin and others, banded together to create their own art show, the Salon des Refusés, or the exhibition of rejects. Buying some of their work in the 1870s and 1880s would have been a better investment than GameStop, but back then, who knew?

The MFA occasionally lets some of its Monets out of the basement, but only to travel. This is the first time in the museum’s long history that all 35 of their Monets can be viewed together, alongside work of some of Monet’s fellow artists, influences and friends.

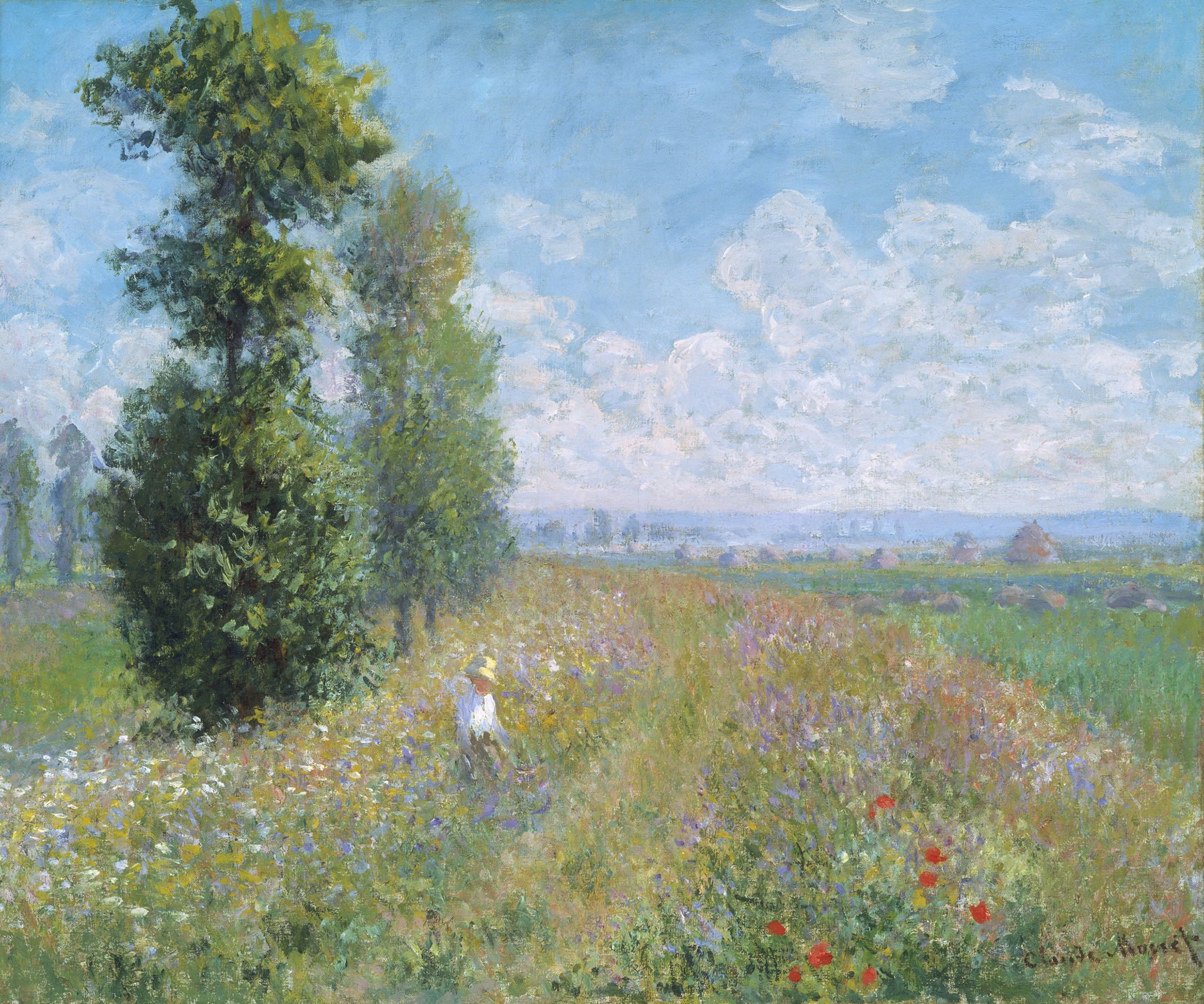

Here you will see all the familiar themes: the Japanese bridge in his garden in Giverny; the haystacks; the lily pads; the front of the cathedral at Rouen; Monet’s wife in her Japanese attire (pictured right); and a number of earlier, unfamiliar landscapes.

Shockingly, the first thing you see when you enter the exhibition is a video of the artist himself—painting, smoking and chatting. The video dates from 1915 when Monet was 74 years old. Talk about an artist coming to life.

Monet’s work became increasingly abstract, and even wild, as the decades went on and his eyesight worsened. To look at early work from the 1860s, you would hardly believe it is Monet, if not for the delicate, almost feminine flair that graces his depictions of fields, mountains and outcroppings along the ocean.

You really have to go out of your way to find somebody who doesn’t like Monet’s work because it is so easily understood and so deeply appealing. You’ve also got to love a guy who can find incredible beauty and variety in haystacks, and who had the clever idea of sitting in front of the Rouen Cathedral, working on a different canvas every hour as the sun changed the way the light hit the stone.

I first fell under the spell of Monet back in 1974 in Paris, taking an art history course as a high school summer student. I had never heard of Impressionism, but once the professor explained their fascination with light, I went to the Jeu de Paume, the extension to the Louvre where Impressionists were chockablock hung to the ceiling before their removal to the Orsay, and the Orangerie to see his magnificent water lilies.

I never hung any Monet posters in my dorm room, but I’m still a fan.

If you love Monet, the bad news is that the remainder of the show is sold out for the end of March, but there are returns available at different moments on the MFA’s website. So keep refreshing the website, and then you, too, like Claude Monet before you, can see the light.

For more information on tickets, visit www.mfa.org.