When Peter Attia was in high school, he wanted to be a professional boxer and studied “the sweet science of bruising” with an obsessive focus. These days he is less of a bruiser, but the obsessive study of science remains. Trained as a surgeon, Dr. Peter Attia is now one of the world’s foremost experts on longevity and the author of Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity, a manual for how to live a longer, better life.

Dr. Attia earned his medical degree from the Stanford University School of Medicine and spent five years at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in general surgery. Today, he is the founder of Early Medical, a medical practice that applies the principles of Medicine 3.0 to help patients lengthen their lifespan and simultaneously improve their healthspan.

Attia is also the host of a weekly podcast, The Drive, in which he has very deep conversations with medical practitioners about the latest scientific research. Subscribers should expect to take notes. They should also expect regular diversions into archery and Formula One racing, two non-medical passions of Attia.

Worth spoke to Attia via Zoom at his home in Austin, Texas. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Costa: The concept of longevity has occupied your research. I think we have a growing appreciation that it is about more than just living longer. How do you look at longevity?

Attia: For me, the simplest definition, and the one that I anchor to, is around the longevity curve. This is a function that describes the relationship between lifespan and healthspan. Lifespan is obviously easy to define because it’s a binary outcome. Are you respiring or not, are you alive or dead?

People just intuitively get healthspan, but I don’t know that they think enough about what it means. Certainly, the medical diagnosis of healthspan leaves something to be desired because it speaks to freedom from disability and disease. I don’t think that’s a high enough bar. We ask our patients to think of a far more sophisticated and personalized view of their healthspan. What matters to you in three buckets—the physical bucket…the cognitive bucket, and the emotional bucket. All of those things speak to quality of life. I think that today, people are thinking at least as much, if not more, about healthspan than lifespan.

One of the examples you often give on your podcast is the ability to pick up your grandchild at age 50, age 60, ideally at age 70. Why do you think that’s an important example?

It’s a very personal example that I think resonates with a lot of people. For me, there’s probably nothing that gives me more joy than playing with my kids and doing things with them that are physical—shooting bows and arrows, riding go-karts, that kind of stuff. I’m pretty fortunate that even though I’m 50, I still have two young kids. My youngest two are five and eight. And everything about playing with them is low, physical, and requires strength, balance, and coordination. To be able to pick a kid up out of a crib, something you and I could do today without thinking about it, becomes really hard when you’re in the eighth decade of your life. To be able to get on the floor and play with kids becomes insanely hard at that age, and then to be able to get up off the floor.

I had a patient once who said something, and I really loved it. He said his goal for the end of his life is to never have to have his kids come to him. He wants to be able to go to them. He meant geographically. He’s like, “I want to be able to travel so that they don’t have to come visit grandpa, great grandpa, I can go to them.” And I said, “Yeah, that’s perfect. But let’s take that one step further. They shouldn’t have to come to you in the rocking chair, you should be able to go to them. If they’re playing sports, you should be able to walk over to them while they do that and engage with them.” So, in some ways, picking a kid up out of a crib is one of many ways we can make it more visceral, something that matters a lot to the quality of our life.

The book is called Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity. What do you hope that readers will be able to take away from it?

I think so much of what it takes to live a longer and better life does not actually require a physician. In fact, very little that those of us who went to medical school learned in medical school pertains to what it takes to live a longer and better life. That’s unfortunate and probably a very sad thing to say, but it is true. Everything that we learn in medical school is geared towards this system that in the book I talk about as Medicine 2.0. It has done heroic things but has not been set up for this [longevity] thing. Outliving requires a new system, Medicine 3.0. And fortunately, much of that can be done with a manual. That’s what this book is. This is a manual to help you think about how to eat, how to exercise, how to manage emotional health, and how to optimize sleep.

I think that today, people are thinking at least as much, if not more, about healthspan than lifespan.”

One of the things that I’ve always respected about you is your willingness to change your mind based on new data. As you were researching the book, was there anything that changed your thinking?

A lot, especially when you consider how long this book was in the making. This book started in 2016. From an editorial perspective, it came to a close in 2022. So, a little over six years of writing and rewriting. It would be hard for me to just tell you one thing, but I think the most profound change in my belief system, in the presence of new data, has been around the work in nutrition. My beliefs in nutrition have changed significantly. Six years ago, I believed that energy balance was not the most important parameter of food. Today, I think the data has been overwhelmingly convincing that energy balance is the first, second, and third-order term of health when it comes to food. Of course, other things matter. The quality of food matters, the balance of fatty acids matters. The nutrition chapter in this book is long for a reason. But the emphasis is orthogonal to where I started six years ago.

If you were to bottom line it, what is your current nutritional viewpoint: exercise and don’t eat too much?

It’s certainly more nuanced than that. When I’m looking at a person, I’m trying to understand three things immediately: are you over-nourished, or are you under-nourished? Are you under-muscled, or are you adequately muscled? And are you metabolically healthy or not? The answers to those three questions determine a nutrition and exercise strategy.

Within the nutrition arm of that, it’s basically going to come down to whether you need to increase, decrease, or maintain energy balance. And what you need to do with respect to protein. That becomes a far more important question. Then, are you low carb? Are you low fat? Are you paleo? Are you vegan? All those questions become completely irrelevant in the context of the most important questions that pertain to overall energy balance—for example, things like visceral fat levels, muscle mass, and metabolic health.

You’re a surgeon by training and a medical doctor, you’ve also done some work for McKinsey. You have a very data-driven and systems-oriented approach to your work. If you could wave a wand and fix one thing about the U.S. healthcare system, what would it be?

Again, here’s a funny example of where my opinion has changed a lot. When I was at McKinsey, I would have had a different answer to this question because I would have been thinking about it through very specific silos that need improvement. I don’t know that there’s a single one that could fix anything in the U.S. healthcare system. It is that complicated. But I will say that a hybrid of the U.S. system and a single-payer system is probably an important first step.

If you move just to a pure single-payer system, you’re going to increase coverage, that’s going to be fantastic. It’s an absolute abomination that there are people in this country that are going bankrupt because of under or lack of coverage altogether. In fact, I believe that healthcare is either the first or second leading driver of personal bankruptcy in the United States. That’s unacceptable. In the U.S., we have people using emergency rooms and things like that for primary care because they don’t have actual doctors. A single-payer system would fix that.

But a pure single-payer system is an abomination in and of itself. Just ask anybody who lives in the UK or Canada how badly that system works. So, you do have to be able to layer on a second-tier system.

I’ll give you a very glib example. This is a true story about a friend who used to spend a reasonable amount of time in Saudi Arabia. He’s an ex-pat from the U.S. I was talking to him one day, and he mentioned that, unsurprisingly, he leaves Riyadh for four months during the summer because it’s unbearably hot. I said, “Man, how hot is it when you come back to your apartment in October?” And he goes, “Oh, no, it’s like 66 degrees.” And I’m like, “how do you know that? That’s Fahrenheit? What do you mean?” And he goes, “Oh, I leave the air conditioning on the whole summer.” And I was like, “you leave the air conditioning on for four months at 66 degrees? That must cost an insane amount of money.” He goes, “No, no, the energy is subsidized. So it costs me like $20 for the whole summer.” And that’s part of the problem with the U.S. healthcare system. It is a total uncoupling of cost and risk.

Speaking of the U.S. healthcare system, Worth has a lot of high net worth individuals in our readership. The current fashion is for executive physicals, which aren’t covered by insurance, but include a battery of tests, full body scans, etc. How much value do you see people getting out of those programs?

Well, I should disclose that I’m the co-founder of a company called Biograph. And while it doesn’t do “executive physicals,” it is kind of like The Four Seasons of diagnostics. It’s co-founded by me and one of my patients actually, and it grew out of a question that he posed to me, which was, “If you could have all of the best diagnostic stuff under one roof,… What would it look like? What MRI would you want to able to do for cancer screening, what VO2 max test, what DEXA scan?”

When you think about “a traditional executive physical” as something you would go and do at any of the big hospitals, they typically involve two days, sometimes one, but typically two days including a battery of tests that start with a physical exam, maybe an echocardiogram, maybe an MRI—but it’s usually some sort of nonspecific MRI—blood tests, sometimes genetic tests, things of that nature. Sometimes they’ll do cardiorespiratory testing, pulmonary function tests, and things like that. There have certainly been examples where those tests have found something that would have otherwise been missed. And so, I think there’s some value in that.

But in my experience, they haven’t yielded many benefits for two reasons. One, the tests that they’re doing aren’t necessarily the very best versions of those tests. And they’re not done with a systems-based approach. The second problem, and I think the far bigger problem, is that there is no implementation strategy. It is one thing if the executive comes in and does two days of wonderful tests. The tests say, “hey, look, your insulin resistant, your lipids are not ideal, your VO2 max is at the 50th percentile,” which by the way, they’re going to probably tell him is fine. We would say that’s horrible your VO2 max must be in the top five percentile. But then that’s it. It’s like we’ll see you next year. The work, the real value is in how do you make those changes? How do you fix these things?

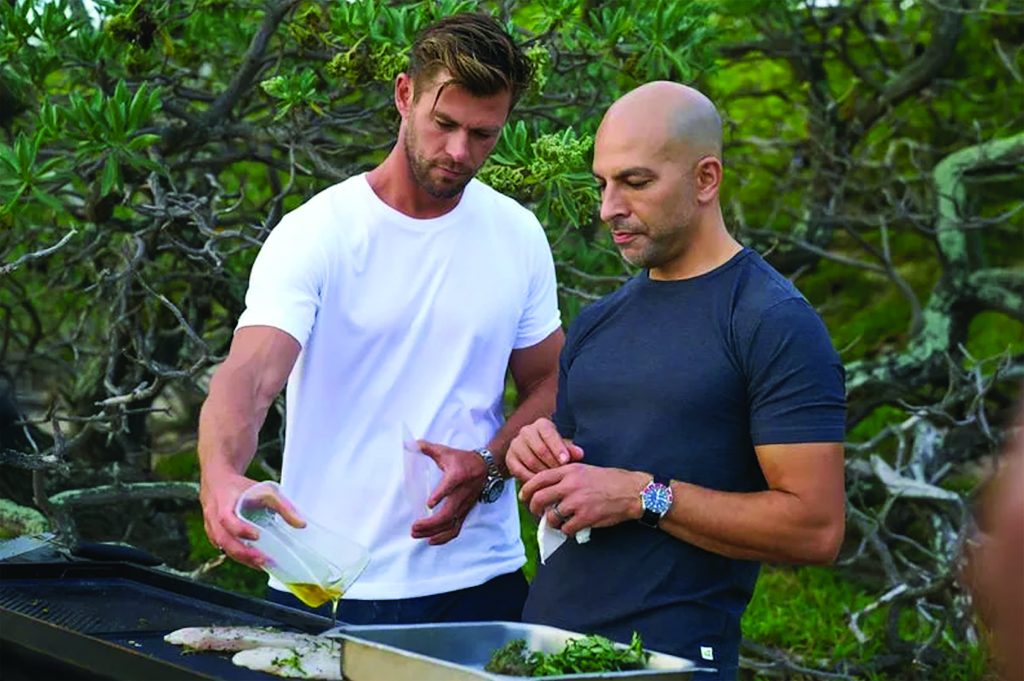

A lot of people will recognize you now from the show Limitless, where you’re the guy pushing actor Chris Hemsworth to the very limits of human capacity. Over the course of that show, you ran some genetic tests on him and gave him some potentially life-altering news. Can you explain how you see the value of genetic tests like that?

I think that genetic tests, like whole genome sequencing, rarely have that much to offer beyond a great family history. That said, there are a handful of genes that we look for, and there are two genes that we care a lot about. One relates to neurodegenerative disease, specifically Alzheimer’s disease, but also to cardiovascular disease called ABO.

And another one is a gene called LPA. That codes for something called Lp(a), which is a pretty strong predictor of cardiovascular disease. The reason we think that it’s important to screen for those things is one, they’re quite prevalent, so you’re not looking for a needle in a haystack. And two—and this is the most important part—I believe that these conditions can be mitigated.

With the example with Chris, two weeks before we go on camera, I get his blood test back and realize that Chris has a pretty unusual gene. He has two copies of this very high risk APOE 4 gene that puts him in the one to two percent of the population that is at significantly higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

So I call Darren Aronofsky, who’s the director, very close friend. I didn’t know Chris well enough yet. But I said, look, we can’t do this live, we can’t film this live for the first time with Chris hearing us. I need at least one discussion with him beforehand. So we did that. In Episode Five, it shows us going through this. And what I said then, and what I’ve said to many other patients in the same situation, is this is something we need to be working on. But it’s not, it’s not a fait accompli, not everyone who has this genetic pairing will go on to get Alzheimer’s disease. But there are a lot of things we need to be doing to act preventatively.

One of our features in this issue breaks down the six pillars of health: exercise, sleep, diet, stress, smoking, and social connections. Is there anything we missed?

I think the pharmacology side of it. There is an important role for pharmacotherapy here. I think that’s especially true in lipid management. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for men, and for women, in the United States and globally. It’s such a behemoth in terms of death, that we almost don’t pay attention to it. Cancer and Alzheimer’s disease get all the attention, but even together they don’t kill as many people as heart disease does. For every woman that dies of breast cancer, eight to 12 are going to die of heart disease. We just can’t lose sight of this thing.

There are really four things driving this disease that we can adjust. Modifiable risk factors include smoking, excercise, energy balance, and sleep.There are many people whose blood pressure can’t be controlled sufficiently with those things. and we have to medically manage the results. We just want to make sure we’re not losing sight of the fact that there’s an important world of pharmacotherapy here that can move the needle for people.

Very good. Well, Peter, all the rest of my questions are about archery and Formula One.

Perfect! Let’s have some fun.

Alas, that story will have to come in a future issue.