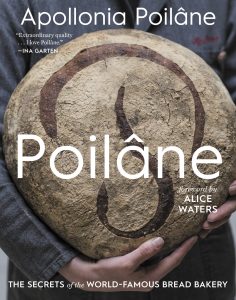

Apollonia Poilâne, 35, has been running her family’s eponymous Paris-based bread business since her parents’ tragic deaths in a 2002 helicopter accident. At just 18 years old, Poilâne took over the bakery, running it for four years from her Harvard dormitory before moving home to Paris and expanding it into an $18 million business with outposts in Paris and London. Last month, during a whirlwind visit to Manhattan, Poilâne met me to discuss her family’s legacy, her future plans and her new book, Poilâne: The Secrets of the World-Famous Bread Bakery.

Exhausted from a late-night book party and a very early morning conference call to her Parisian bakers, the carefully spoken, whippet thin CEO sustained herself with small bites of Valhrona dark chocolate, a handful of popcorn and a deep enthusiasm for the stories of the iconic Parisian haunt her grandfather opened in 1932, still decorated with the artwork the neighborhood’s artists used to barter for their bread.

Q: What has been the most challenging aspect of your work over the past 17 years?

A: Seventeen years ago, I was a high school graduate taking a year off before I went to college. I was working in the bake house, and then suddenly I was running the company. There have been challenges for sure, but I view them as opportunities. This may come from the fact that I’m an equestrian and I jump. How do you handle the horse to get him across these different obstacles? It’s an image that really represents the way that I view running my family’s business. I know where I want to go.

Was that always your perspective? You took over the business at a tender age.

It is a tender age, but I had been groomed by my father to take over the family business. It wasn’t unexpected. It just happened much sooner than planned. A professor from INSEAD recently told me, “We always overlook the fact that sons and daughters of entrepreneurs grow up in an environment where they’re immersed in their parents’ world. That is an education, and they are all the more legitimate as leaders.” It really captured the way I felt when I took over the family business.

What was it like to leave the French system and study in the U.S.?

Studying at Harvard and benefiting from the liberal arts education really was key in making a difference in my thinking. It was a very structured experience in France, growing up. But speaking for my adolescent years, and definitely for my college education, this was the right thing, for the openness, the diversity of the student body and of teachers and the exposure to different forms of knowledge.

You wrote about encountering new ingredients in your travels, things like miso or yuzu in Asia, or oat milk and corn bread in Cambridge, Mass. How do you integrate those into your brand, which is so deeply associated with French sourdough?

Actually, it’s very easy, because at the heart of the Poilâne tradition is that conversation between past and present. My parents were the first people who introduced me to sushi, and for me, it’s not really one or the other. It’s part of that conversation between culture, between times. It really is part of who my parents were, and what they instilled in me and my sister, as a form of education, saying we need to be curious and to have an appetite for that.

One of the things that is very distinctive about Poilâne is the work we do on the quality of the grains that we use. Historically, we’ve used wheat and rice flour. I added corn for breads, and we have now seven grains for the biscuits and we’re adding millet for the holidays.

I’m curious about why you’re including corn. It’s often reviled in the U.S., criticized for being high in sugar and sometimes a GMO crop.

It’s the same perception for us. First of all, my distinctive outlook on bread is it’s this crossroads between cereal grains and fermentation. From that standpoint, we look at the quality of the grains that you have. Yes, corn has the reputation of being water thirsty and of being GMO, but we use an organically certified corn flour. Most of the flours we make bread with have zero traces of pesticide, because that’s part of what we require, but they don’t necessarily all have organic certification. The beauty with certification is that it is a shortcut, but it doesn’t necessarily benefit the customer or the farm.

You employ 160 people in France and 40 in London, produce up to 5,000 loaves daily and ship all over the world. That’s a lot to manage. Do you think about going public or going into a partnership?

No. If you go to 8 Rue du Cherche-Midi, you’ll see a neighborhood bakery. Across Paris, we have four of those and a café. We have two shops in London. One is the bakery—similar to the four in Paris—and we have a café. We also have distribution, and the scope of our business is that mix between B-to-C and B-to-B businesses.

When my father was running the business, the natural path was to industrialize and make production lines, but my parents did something absolutely extraordinary, developing the retail network and the distribution. My father’s take was, “To make bread that will not change, you don’t change the quality.”

He worked with my mom, who was an architect, to design a place that would allow for that by compiling 24 different ovens, one next to the other. What’s remarkable is that it gives us the capacity to do our production today and increase it tomorrow, and if the day after tomorrow is a slow day, because it’s a holiday or something, we can do half of that amount.

I’m not interested in an IPO, because I don’t think it’s the way that I see my business’ future. Poilâne is a different world, a different tradition and a different ambition.

What is your ambition?

I want to feed communities, but I’m interested in doing it with the quality bread that I bake. It takes us six hours to make a loaf of bread, and nine months to train a baker. The landscape of our craft is quite unique.

What are the enduring lessons you learned from your parents?

I think their teaching was to be passionate and open-minded. We’d spend time on farms. Living on a chicken farm in Brittany is one of my most vivid, wonderful memories. I learned how to slaughter chickens, and I learned how to market them. I was 12 or 13 years old and we lived there for a few weeks. I also worked at a florist. What an education, learning how to prepare the flowers, keep the flowers, make bouquets. I could see the other kids didn’t have that same upbringing. I had the sense that I had original parents, and I liked them for that.

Are there business decisions that you’ve made, where you think to yourself, Okay, this is probably what my mom and dad would have done, or moments when you wish they could give you advice?

Never. Because if there’s one thing that I learned from them, it’s that that’s not the way it works. They gave me their education, and their spirits nurture me, but they’re my decisions, and it’s here and now. That has been very clear to me since the time my parents passed away, that our family tradition is to look forward. They experimented with past and present techniques to move forward, to shape the future.

What a gift, not to have doubts and not to feel beholden.

Of course, I have doubts. But I do not base my decisions on what my parents would have done. I sometimes have caught myself thinking, My parents would have gotten a kick out of this situation. But it’s more something to question, to think through about what’s going on and how does it play for me in finding my direction?

Are there other family businesses that you find inspirational?

I love the Japanese pastry makers Toraya. I think they have the most beautiful cakes and I love their wagashi pastries. They have a shop in Paris, and they change the flavors every two weeks. The company was founded in the 16th century. They’re the providers of the Imperial Courts. They are an amazing family business. That conversation about past and present, they really live it daily.

What do you wish your parents could see?

I think that they would appreciate my outlook on my craft, and my sense that bread is the crossroads between grains and fermentation. I’m very proud of my parents having fed my outlook. That’s what feeds the sourdough. It’s the product sourdough, but also that sensibility and the family spirit in the sourdough.

Friends of my parents have told me a couple of times throughout the years that I do something that my parents always did. When I’m at a table, I’ll take a piece of bread, and I’ll open it up and smell it. That’s the way that I test the bread. Because when you smell it, you get the sense of “Oh, is it whole wheat? Is it white flour? What’s going on?” I am my parents’ daughter. It’s part of our tradition.

Tradition tends to be looked at as something in the past. But a year and a half ago, we changed up our brand’s logo. We used to have this script letter “P” and we changed it to a straight letter, which is so much more visible. We also added a tagline to our logo, and we don’t always use it, but it’s contemporains par tradition (contemporary by tradition). That’s who we are. We live for that conversation between past and present. We honor our past and we move forward.

Part of your family tradition is that you’re a third-generation company. What’s it like working with your sister?

My sister Athena works with me, but more on the strategic side. It’s all the more impressive since she’s a young mom of an 11-month old, which is something else that I’m sure that my parents would have loved to have witnessed. Our father would have been an amazing grandfather. He had two daughters and was an extremely playful man, and so I can only imagine how much fun he would have had with my nephew.

You wrote in the book, “These days, when I bake at night, my thoughts center on my dreams for the future.” What are some of those dreams?

The first thing that I should say is that you have to imagine when I work at night, I’ll start at midnight, and I’ll finish at 6 a.m. These are not normal hours that a person usually works. It’s really hard around 2 and 3 a.m., and you start thinking, Why is it that you’re in here doing what you’re doing? I really wanted to build something that was representative of the spirit and the rhythm of the family’s business and explain to people why it is a beautiful craft, but not shying away from this hardship. I say this because it is because I’ve seen how tough it is. I see how my father overcame many difficulties since he began in the business when he was 14.

His revelation was bread is connected with everything. It’s an amazing business, and it’s an amazing starting point to connect with people. For me, the nighttime explorations in the third part of my book are really there to show how that culture for bread has fed the wealth of opportunities it opens up to you when it comes to business expansion and product development. My role as the CEO of Poilâne is both that of a baker, because that was my training, but it’s also troubleshooting on a daily basis, because invariably, things happen, especially since it’s a craft where intrinsically, the ingredients react.

Sure, it’s a living organism.

It’s living, exactly. With that outlook, I hope that I’m going to be able to hand over this company to a fourth generation. I have a very personal love for my business, and if there’s a fourth generation, they need to build that interest. My sister has an entirely different role, but is a great supporter of my work on operations. When we work together on the strategic aspects of the company, I love the conversations we have. We have conversations between past and present.

You’re half-American, and have lived in the U.S., where we often demonize bread. What do you wish Americans knew about bread, and have you seen changes since you were a college student?

It’s been amazing to see a rise of the amazing bakers that I have met over the past 17 years, building an American bread tradition. I couldn’t cite them all, but whether it’s Steven Sullivan at the Acme Bread Company in Berkeley or Chad Robinson at Tartine in San Francisco or the ladies at She Wolf in Brooklyn, there’s a wealth of bakers across this country that are carving their own paths.

Your grandfather allowed the bohemian neighborhood artists to pay with paintings, and Salvador Dali famously worked with your father to create an entire room out of Poilâne bread. Are you still allowing artists to pay you with their work?

One thing that speaks to our unique outlook on bread is the link between bread and artists that was started by my grandfather, and that still goes on. This fall, a Canadian artist made me the most beautiful painting of a little stack of my biscuits with a rose. It’s one of my favorite things.