The entire time you work and save for your retirement, say, 30 years, there will be multiple bull markets, multiple recessions and perhaps a dramatic bubble or two. If your retirement lasts a couple of decades, there will be both bull and bear markets, which will create ups and downs in your investment portfolio.

While saving for your retirement, if you stay the course on a growth portfolio and contribute consistently, you’ll end up buying more in an asset when it is cheaper, and less when it is more expensive, which is exactly what you should be doing.

Most retirees, after leaving the workforce, basically contribute little to their investments. Instead, they rely on an existing portfolio to deliver the income they need to live a lifestyle they expect to enjoy. Meaning, they plan for a consistent rate of withdrawals. But, once withdrawals begin and steady contributions end, the portfolio is more vulnerable to market fluctuations, possibly depleting it earlier than intended.

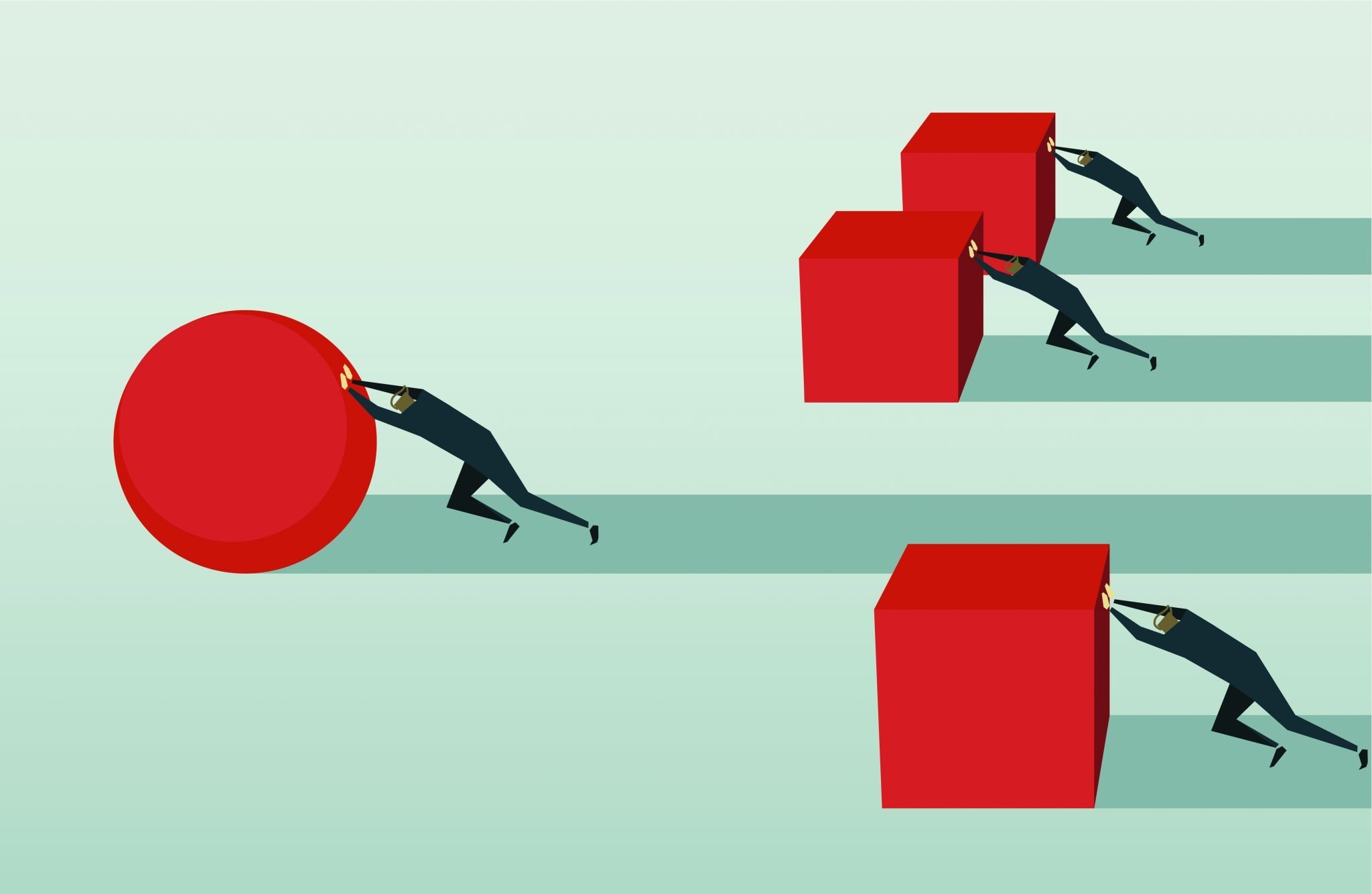

The conventional wisdom is that increased risk during the accumulation phase can help your returns, while decreased risk during the distribution phase can preserve your capital. These investment strategies can impact how much your portfolio fluctuates up or down. Just as significant is the timing of when these portfolio fluctuations occur. This is called the “sequence of returns,” the order in which the portfolio experiences positive and negative annual returns.

Consider those retirees who targeted 2008 as their retirement start date. Let’s say those 2008 retirees were figuring on a standard 6 percent withdrawal on a $1 million portfolio, for an annual income of $60,000. Practically overnight, the value of their portfolios likely dropped dramatically due to the great recession. By the beginning of 2009, with a diminished portfolio value of, say, $750,000, their 6 percent annual income will have dwindled to $45,000. And if they held to their $60,000 withdrawal, they could have further diminished their portfolio to a point where it might never return to its original value.

But what about people who retired with that same $1 million portfolio in 2010 when the market was already vigorously rebounding? Their portfolio will have likely experienced five consecutive years of positive returns. Those portfolios are probably better positioned to withstand both the inevitable bear markets of the future and the systematic withdrawals taken to sustain a retiree’s lifestyle over a longer period of time.

Of course, the retirees of 2008, just like most people, never saw the great recession coming. And those who retired in 2010, if they were honest, never figured that a market so beaten down would eventually reach new record highs.

With such unpredictability, is there a way to avoid the pitfalls of an ill-timed retirement?

While no one can predict the future, there are a few things you can do to shield your retirement portfolio, at least somewhat, from those down times. For example, taking on extra risk, or volatility, during the accumulation phase can improve returns. As you approach the distribution phase, reduce volatility by diversifying your retirement portfolio within multiple asset classes such as cash, fixed income and stocks. To avoid selling stocks when they are down, structure your cash flow to come from the cash allocation while harvesting additional cash from stock dividends, bond interest, maturing bonds and the rebalancing of allocations.

Finally, make sure your financial advisor has the depth of knowledge and experience to manage your retirement plan. This means an advisor who understands that to some extent, timing is everything when it comes to your retirement portfolio’s sequence of returns.

This article was originally published in the December/January 2016 issue of Worth.