Editor’s note: On June 8th, 2023, Worth Media is hosting our Cities Summit at the Mills House Hotel. We sincerely hope that you will be able to join us for conversations on topics ranging from building resilience in the face of climate change to ensuring transparency and accountability in city councils. Innovation and the Rising City is an essential gathering for anyone interested in shaping the future of American cities. Register here.

For nearly 20 years, this pretty little South Carolina town has had a hold on my heart. It’s certainly charming: Graceful old Southern mansions line its shady streets, Spanish moss whispers in its massive live oak trees and candlelit dinner parties twinkle from its grand piazzas. And that’s to say nothing of its nationally acclaimed restaurants, pristine barrier islands and robust art scene.

In the past decade, an exponential uptick in yearly visitors and a mass exodus from cosmopolitan epicenters like New York City have brought an influx of money, talent, and sophistication to the city. Charlestonians joke that they have “list fatigue” after topping Travel + Leisure’s and Condé Nast Traveler’s best-of lists for nearly a decade. But Charleston brews a strange magic. Somehow, this sweet South Carolina town is even greater than the sum of its parts. There is something deep and important at work here, and you can feel it.

The sultry Southern air hits me as soon as I step off the plane—the briny scent of the Atlantic mixes with the smells of loamy soil and the cool green shade of maritime forest. It’s early spring in Charleston, and the sunshine feels like a balm on my winter skin. My God, it’s good to be back.

I’ve spent the better part of the last two decades leaving and returning to Charleston. I’ve left it for Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Colorado, and during the most recent stretch, New York City. But here I am again, house hunting and plotting the next chapter in the love affair.

I first moved to Charleston in 2005 to go to the College of Charleston. I’d applied sight unseen, lured by the promise of piazzas and Spanish moss. Back then, the city was just starting to gather momentum. Real estate was on the rise. Joe Riley had been mayor for nearly three decades, and his bold support for the arts was paying off. Since its inception in 1979, Spoleto Festival USA was attracting talent like Yo-Yo Ma and Philip Glass, and discerning aesthetes from all over the world. Neighboring Kiawah Island was hosting national golf championships. And chefs like Mike Lata and Sean Brock (now James Beard Award–winning, Top Chef and Chef’s Table celebrities) were building some of the most innovative menus the South had ever seen.

If pressed, I’d say the chefs led the charge. In their quest to create extraordinary food, guys like Lata and Brock established a robust network of local farmers and fishermen. They invested time and money into cultivating heritage strains of seeds, rice, and animals and, in doing so, built out a full supply chain, a viable farm-to-table economy unique to the Carolina Lowcountry. Their cuisine reflected the quality of their ingredients alongside a brilliant, focused talent. Build it and they will come: Foodies discovered Charleston, and the town has never been the same.

Looking back on those early days, Charleston lacked the polish and elegance it has today. Upper King Street—now packed with swanky cocktail bars, world-class restaurants and a West Elm—was still a bit funky. A dusky little bar called the Trusted Palate (where HōM now serves up trendy burgers) featured Cary Ann Hearst and Michael Trent of Shovels & Rope who would bring the house down for 30 friends and fans every Thursday night. (I saw them play a sold-out show at the Beacon Theatre in Manhattan.) The historic district still had pockets of dilapidation and disrepair. The manufacturing industry had not yet discovered Charleston (looking at you, Boeing, and Volvo). But you could feel things happening. The energy of the city was electric.

History

I stroll south on Upper King Street with a coffee later that afternoon. Crossing over Broad Street lands me in the heart of Charleston’s most photogenic neighborhood. The peninsula, pointing south (much as the island of Manhattan) at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper rivers, is surrounded by a network of barrier islands. A few are beachfront and boast some of the prettiest shoreline in the state; others are tucked leeward, covered by dense maritime forest and bordered by tidal creeks and vast expanses of Lowcountry marsh.

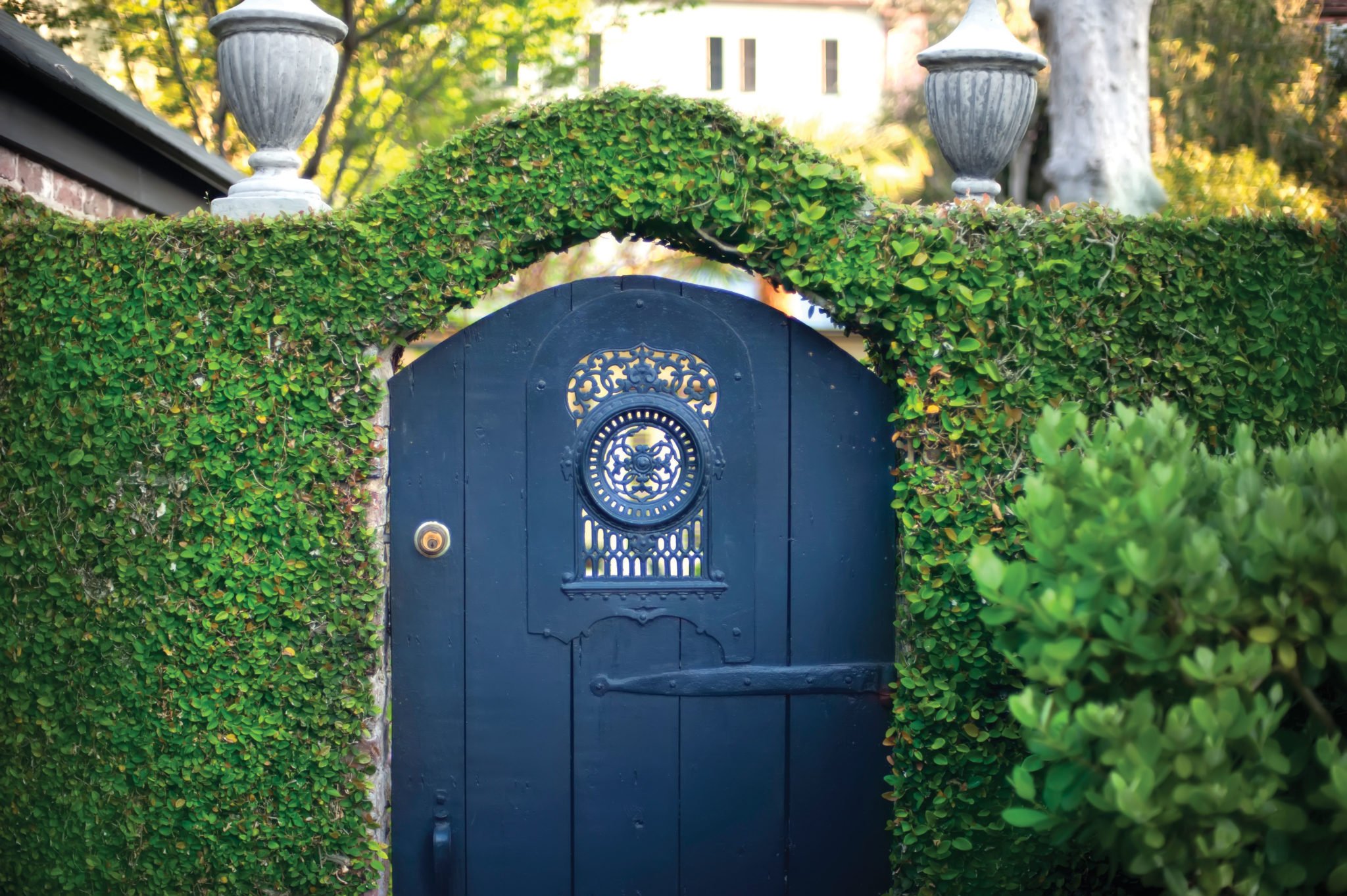

Historic Charleston is preserved to perfection. Confined to less than five square miles of 18th- and 19th-century buildings, Charleston is dubbed the Holy City: No buildings south of Calhoun Street can be higher than the city’s countless church steeples. Tight preservation laws have kept the extraordinary architecture intact. The shady lanes south of Broad Street boast beautiful mansions, manicured gardens, and lucky Charlestonians cruising around on fancy golf carts with G&Ts in hand. I peek past wrought iron gates to vast lawns and crystalline plunge pools. On Lamboll Street, between Legare and King, a muster of resident guinea fowl struts around at all hours of the day. The scent of gardenia and jasmine hangs thick in the air, and someone plays Chopin from an open window. It’s like a damn fairy tale.

A few blocks down, White Point Garden marks the Charleston Battery, the southern tip of the peninsula. The small park is magnificent, graced by centuries-old oak trees, a dense, shady canopy alive with terns, herons and gulls, and it is lined with some of Charleston’s most resplendent houses. A raised seawall borders the park, and from it you can see Folly Beach and James and Sullivan’s islands. On the horizon, at the mouth of the estuary, sits Fort Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War were fired. Today sailboats fill the harbor, and just a few hundred yards to my right, a dolphin breaches in the afternoon sunlight.

Let me put it this way: When you know, you know. Charleston is intoxicating. If you’ve dined in her restaurants, swum in her ocean or walked her cobblestone streets at twilight, you’ve been indoctrinated. It’s part nostalgia; the city sparks an innate longing for a simpler way of life, the proverbial Mayberry. But there’s also a surprising level of sophistication. The Charleston cultural milieu is nothing short of cosmopolitan these days. In Charleston, you can have your cake and eat it too.

Restaurants

I have a reservation at The Ordinary that night. I arrive a bit early so that I can cozy up to the bar with a daiquiri and chat with my favorite bartenders. Lata’s (and partner Adam Nemirow’s) second installment, the Ordinary, is nothing short of extraordinary. Built out in an old, cavernous bank building, the space has a worldly-but-whimsical sensibility. The menu is famous for its seafood tower (a smorgasbord of fresh local oysters, crab, lobster, caviar and shrimp), but the lobster rolls are to die for, and the chowder just might make you cry. I have eaten technically good food all over the world—perfectly seared Wagyu beef and expertly shaved truffle—but restaurants like the Ordinary, FIG, Chez Nous, Renzo, Butcher & Bee, and Husk serve up dishes that taste so intentional, where the ingredients speak for themselves and represent the terroir and merroir of the place. At the risk of sounding trite, it’s the kind of food that feels like an experience (even to the experienced), food that represents the heart and soul of a place and its people.

The restaurant scene is the Charleston touchstone for visitors and residents alike. To locals, the chefs seem like celebrities, and it’s always a thrill to spot them in the wild and say hello. This fervent support feeds a kind of infectious energy around the city’s culinary achievements and the creative culture in general. And Charleston is a wonderfully social town, with invariably packed openings, panel discussions and launch parties. The creative community is outsized, boasting a wealth of talented painters, sculptors, performers, photographers, designers and even a resident taxidermist with clients worldwide.

Tim Hussey, a longtime friend of mine and a contemporary art darling of Charleston, has had multiple stints in New York, Los Angeles, Santa Fe and Paris, but he’s always come back to his native Charleston. “All the institutions here know who you are, and you have dedicated collectors,” he says. “For such a small town, Charleston attracts a very sophisticated audience. Buyers come to me. I don’t have to go up to New York and peddle my wares.” The internet agora has allowed the creative community in Charleston to stay put, to flourish and develop an essence all its own. “It’s truly one of the most idyllic places to live—especially after going out and seeing the world,” Hussey says. “Leaving gives you a chance to put it into perspective, and it always seems to win.”

The art and food scene has had a compounding effect. With young, ambitious artists come hip cafés, flower shops, wine stores and high-end retail. Oh, the shopping! Walk the narrow streets of the city’s shopping district and you’ll find everything from Gucci to St. John, Cynthia Rowley to Billy Reid. Elegant ladies with designer handbags stroll King Street, shopping for Comme des Garçons and Chloé at boutiques. Make no mistake about it, there is money to be spent in Charleston.

I would be remiss not to acknowledge that the city and its history are indelibly married to the atrocities of the American slave trade. So much of Charleston’s food, music, language, and customs come from the vibrant cultural wealth of enslaved Africans. This homage, however, makes Charleston incredibly self-conscious and requires the evolution of the city to be intentional. Charlestonians remain in constant conversation with this complicated history, weighing the present always against this painful past. But it’s clear that Charleston tries. The people who live here care, they pay attention, they connect.

Shopping

I stop by Monarch Wine on Upper King Street to pick up a few bottles for a dinner party. The lineup is incredible—everything from pét-nats to pipeños, a more thoughtful selection than any wine store I’ve ever happened upon in NYC. I say as much to the proprietor, Justin Coleman, and he laughs. “Well, Charlestonians are about as hip and sophisticated as they come,” he says. A New York transplant, Coleman worked as a sommelier for over a decade. Since moving to Charleston, he has been astonished by the city’s cultural mise-en-scène. “Charleston doesn’t make sense,” he tells me. “It should be this sleepy little Southern town, but for its size, it completely outperforms. I still have trouble wrapping my head around how a city this small can offer what it does.” I buy a bottle of Cuvée Marguerite and head to dinner. Sophisticated indeed.

Architecture

Some old friends have restored a 3,400-square-foot Charleston single home, on Anson Street, in the southeast quadrant of the city. I arrive at dusk and the sounds of Rodrigo Amarante drift from the windows. The house is an architectural dream—a classic example of a Greek Revival single home with 12-foot ceilings, original crown molding, and two stories of wide piazzas to catch the ocean breeze. There’s even a little kidney-shaped pool out back, shaded by mature loquat and fig trees. The house makes my New York apartment feel pretty puny in comparison. There is a slight chill in the air, and we dine alfresco on the lawn, candlelight dancing against the dark canopy.

Don’t be fooled; Charleston real estate isn’t cheap. The city has been in an exponential boom since 2009, and property values have increased by nearly 70 percent in the past two decades. The average selling price south of Broad Street falls between $2 and $3 million these days. A lot of the big money, says real estate agent and my old friend Carter Rowson, comes from metropolitan areas like Washington, D.C., Boston, and New York, buyers lured by the pleasant quality of life and urbane atmosphere. “Most of the time people just need an internet connection to do their job. So they choose lifestyle,” he says. “I see a lot of people who come down from New York on Thursdays and commute back up on Monday morning.”

Spared the industrial revolution that transformed northern cities, Charleston, and other small Southern cities like it, never got the teardown-rebuild of the modern skyscraping city. Careful preservation laws (Charleston was the first city in the nation to instate a preservation society) have kept history intact. And maybe that’s what’s so exciting about real estate in Charleston: You’re buying a piece of history. Root around in your backyard and you’re liable to turn up shards of pottery; explore your old cistern and you might find the remnants of a fanner basket. The whole city is one big treasure trove.

I take a circuitous route to my hotel in the midnight hour, the sounds of crickets and night birds echoing through the silent streets. My walk takes me past the graveyard at the Circular Congregational Church, with monuments dating back to the late 1600s. I stroll past Catfish Row, the setting for Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess; past the Heyward-Washington House, where George Washington slept on his visit to Charleston in 1791. The jasmine-scented air is practically steeped in history.

Lowcountry

I am up early on Saturday and swing by the Daily on King Street for a green smoothie and an Americano. I drive south out of town, crossing low causeways through James and Johns Islands. Massive live oak trees line the shady back roads, creating a dappled tunnel of greenery.

Charleston has dreamy neighborhoods, incredible food, and cosmopolitan pizzazz. But this golden little town also sits smack-dab in the heart of some of the country’s most remarkable wilderness. With the ACE Basin to the south, the Francis Marion National Forest to the west, and Cape Romain to the north, just 20 minutes out of the city you can swim in the ocean, boat the vast inland waterways, or hike through tall pines. This access to nature only compounds Charleston’s allure.

The South Carolina Lowcountry encompasses these coastal plains southeast of the Sandhills, a fall line that runs north–south through the state. It is utterly distinct, defined by a unique profile of flora and fauna. When you get onto some of these barrier islands, you’d swear you were in the tropics. Palmettos rustle in the warm wind, and the birdsong is a dense cacophony. Deeper into the forest twist live oaks dripping with Spanish moss. And then there’s the marsh. It takes time to understand its magnificence—to see the way the light shifts through its expanses of cordgrass, to hear the quiet clicks of fiddler crabs at low tide.

Forty-five minutes by car, 20 by boat, Kiawah Island feels like a world apart. I take a kayak from the Cassique boathouse into the Kiawah River and paddle along the backside of the island. I am startled when three dolphins breach just ahead. Even in spring, before the cordgrass turns to the electric green of summer, the marsh holds and wields the morning light—glinting golden and dusky mauve in the sunshine.

Kiawah is a slice of paradise—with 10 miles of pristine beach, a five-star resort, a private club that boasts James Beard Award–winning chefs, and golf courses designed by the likes of Fazio, Watson, and Dye. Kiawah has also topped its fair share of best-of lists and in 2021 will host its second PGA Championship. If you’ll forgive another comparison, Kiawah is to Charleston what the Hamptons are to New York City. Real estate on Kiawah is some of the most expensive in the state, and most of its second-home owners hail from the Northeast, Chicago and Atlanta. The display of wealth is subtle—hidden, even. Elegant clubhouses nestle into the dunes and Shingle-style mansions peek out from the maritime forest. Like all of South Carolina’s Sea Islands, Kiawah is an ambrosial mix of live oaks, sun-washed palms, briny mud, and windswept dunes. And if you paddle east toward the Atlantic, it actually still feels a bit wild.

As I plot my next incarnation as a Charlestonian, my head swims with visions of neighborhood wine bars, spontaneous afternoon jaunts to the beach, morning coffee on a deep porch. There is a reason Charleston keeps topping best-of lists. There is something that draws you to this place—its history, its people, its profound beauty. Simply put, there’s no place like the Lowcountry, Toto. And the world has taken notice.

This story was originally published on November 4th, 2019.