Since decamping from New York City during the pandemic, I have developed a new understanding of American car culture. Not only did I purchase my first new car, a Ford Bronco Sport, but I’ve learned to read the landscape of makes and models as they drive by on country roads. And I’ve noticed as Tesla has slowly replaced Subaru and Prius. Even so, watching the EV transition unfold locally is different from understanding its consequences globally.

Electronic vehicles comprised about 9% of all new cars sold globally last year, which is up from 2.5% in 2019, according to the International Energy Agency. That trend isn’t going to change with gas prices surging and the international community scrambling to reduce its dependence on Russin oil even further. The transition to electric vehicles is going to be one of the largest industrial transformations in the history of the planet. And as usual, there will be winners and losers.

One winner, at least for now, is Tesla. With a valuation of over $1 trillion dollars, the company is nearly synonymous with electric vehicles. Nearly half of all EVs sold in the U.S. are Tesla. Despite some high-profile setbacks – the latest being the aborted production of the CyrberTruck – Tesla has managed to outcompete other luxury car markers. Even in the midst of pandemic supply problems, Tesla increased sales: According to The New York Times:

Tesla said it delivered 310,000 vehicles from January through March, up from 185,000 cars during the same period in 2021, roughly in line with Wall Street’s expectations. The nearly 70 percent increase was in contrast with major carmakers like General Motors and Toyota, which reported big sales declines on Friday because of shortages of key components.

That seems like good news, and it is good news for Tesla and its shareholders. Unfortunately, it is just one part of the EV story. When you take a more global view, the U.S. EV industry faces existential threats to its supply chain that could hobble any chance of catching up with China, which is leading the EV revolution globally.

Looking at Tesla’s success, you may think the U.S. is leading the EV revolution. That is not the case, according to Michael Dunne CEO ZoZo Go, Driving ith Dunne podcast. Dunne, who has lived in China, thinks Americans misunderstand both the quantity and quality of Chinese EVs. He spoke at the Techonomy Climate conference last week.

“China has the lead in electric vehicles sales,” Dunne says. In 2020, Chinese EV sales nearly tripled to 3.4 million. That means more EVs were sold in China that year than were sold in the entire world in 2020.

And many of these are luxury cars, not efficiency models. Dunne says, “China today is building world-class vehicles that can challenge Tesla.”

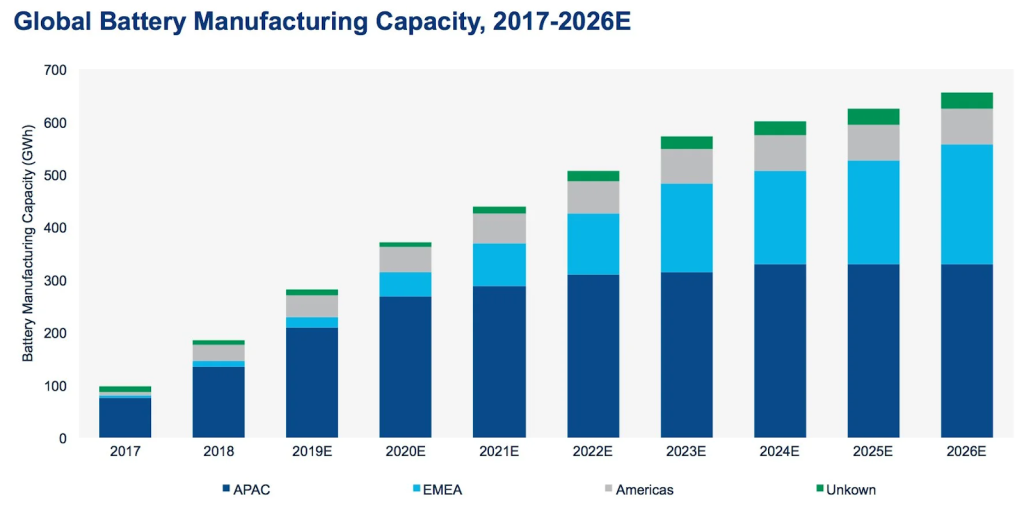

Competition isn’t the real problem for the U.S., according to Dunne. It is access to the supply chain needed to manufacture the EVs, in particular the batteries used to power them. Companies like CATL and BYD are unknown in the U.S., but make more than 75% of the world’s EV batteries. Put simply, Dunne says, “We don’t even have our own battery manufacturers.”

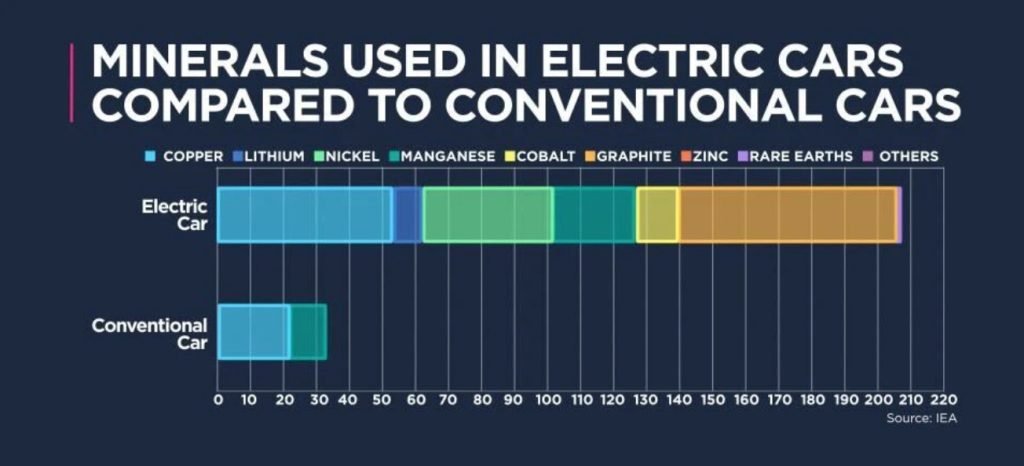

Worse still, making EVs requires rare minerals that are increasingly in short supply. According to the IEA.org:

In 2021, the price of steel rose by as much as 100%, aluminum around 70%, and copper by more than 33%, affecting both conventional and electric cars. For electric cars, additional challenges were posed by increased prices for materials needed to manufacture batteries: the price of lithium carbonate increased by 150% year on year, graphite by 15%, and nickel by 25%, to name just a few.

Even when extracted, those minerals are often sent to China for processing, in part to avoid the environmental regulations in the U.S. Processing rare earth metals is a dirty business. Dunne says, “Maybe we need to get our hands dirty and make some tradeoffs in the name of national security.”

That sounds ominous, but two takeaways are clear. First, the U.S. is trailing China when it comes to EV production and adoption. Second, we are completely dependent on China to supply us with the components to make them. Both of these are big problems, not reflected in Telsa’s soaring sales and stock price.

As Dunne says:

Being overly dependent on far-flung supply chains was something America could get away with within a peaceful world. But a giant, violent storm has unleashed itself in Ukraine. And things could take a turn for the worse.