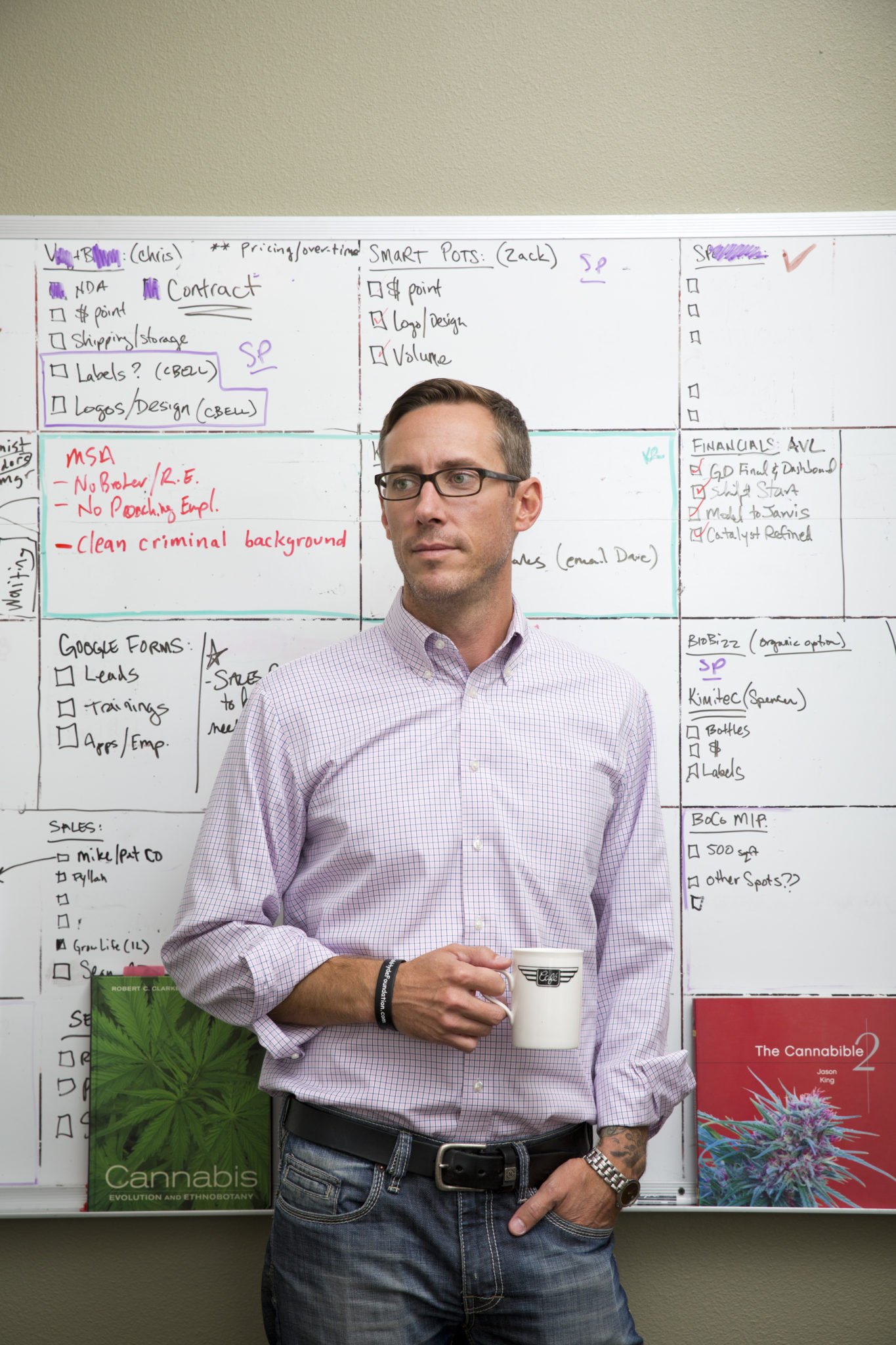

Driving northeast on Diagonal Highway out of Boulder, Colo., corporate offices give way to scrubby foothills and barley fields beginning to go fallow after the late summer harvest. About eight miles out of town, you’ll pass, probably without really noticing it, a small, generic office park along a stretch of state highway known as Gunbarrel. Inside is the headquarters of Shift Cannabis, one of two cannabis-related businesses cofounded by one of the leading entrepreneurs in the burgeoning business of marijuana, a 37-year-old former lawyer named Travis Howard.

At 9 a.m. on a brisk fall morning a few weeks ago, Howard was pouring his coffee and debating whether it was even worth going into his corner office— every time he does, he quickly leaps out of it to talk business with his management team. Howard is thin, with close- cropped brown hair, and was wearing an oxford shirt, blue jeans, black plastic glasses and a Movado watch a girlfriend gave him in 2000. But for the tattoos that adorn his forearms, he could pass for a small-town English teacher. His left arm is the favored canvas: It depicts the scales of justice with the astrological signs of his wife—Libra—on one and his children—both Pisces—on the other. The scales float above a raging sea, underneath which is emblazoned the mantra, “Live the Dream.”

Shift Cannabis does two things: It partners with high net worth clients interested in starting cannabis businesses, and it co-owns and manages cultivation and retail operations in New Mexico, Maryland, Alaska and Hawaii. It works closely with Howard’s other company, Green Dream, a marijuana grower and retailer that targets the high end of the cannabis market. (For industry types, “cannabis” is the preferred nomenclature; it refers to the plant rather than the drug, and it sounds more clinical than marijuana slang.) Green Dream sells its hand-tended cannabis for about $300 an ounce, almost three times the average wholesale price of an ounce of pot in Colorado, which, according to the state’s Department of Revenue’s Marijuana Enforcement Division, is about $117 per ounce. Green Dream is succeeding by focusing on characteristics similar to those emphasized by other luxury goods makers: quality, craftsmanship, scarcity and a carefully cultivated image of authenticity.

It’s big business, and likely to get much more so in the near future. For Howard, though, Green Dream and Shift aren’t just about profits. He says that he’s also driven by a desire for social justice. Growing up, he witnessed the lives of friends and his own brother steamrolled by a national drug policy that targeted pot smokers as if they were heroin dealers. Now, he wants to legitimize the industry by rebranding cannabis as a luxury good and converting the nation’s elites, from Wall Street to Silicon Valley, into cannabis users. “I’m talking serious, traditionally powerful, financially powerful men and women,” he says.

The epicenter of the legal cannabis industry in the United States, Boulder is a booming tech hub with a counterculture flavor. Tech firms including Sun Microsystems, IBM, Nest and Google have brought wealth to the area, but eco- conscious programmers drive Priuses and Subarus to work past vegan restaurants, microbreweries and dreadlocked students from the University of Colorado. Local hotels offer the “Boulder Discovery Map,” a tourist guide with icons for El Loro Jewelry & Clog Company, Glacier Homemade Ice Cream and four cannabis dispensaries. A “Colorado Cannabis Tourist Map” lists 47 Denver and Boulder-area dispensaries. It comes with coupons proclaiming, “Buy an eighth, get a FREE pipe!” from a company called Organix and “$5 OFF for 3 COOKIES, 10mg” from Mile High Wellness.

Boulder may be the capital of cannabis, but even so, the industry feels very young here, and somewhat amateurish. Lines to see a “budtender”—basically, a marijuana sommelier—are ubiquitous, and “edibles” come in ugly plastic canisters. At dispensaries around town, shoppers can peruse cannabis flowers stuffed into jars and invariably presented as “the very best” cannabis you can buy.

The lack of polish is understandable: Many dispensary owners started in the black market and lack conventional retail experience; it’s not like they ran J. Crew stores beforehand. Plus, cannabis hasn’t been legal for long. Colorado voters passed Amendment 64, which legalized recreational cannabis, in November 2012, but it wasn’t until January 1, 2014—after Colorado hammered out regulations and the U.S. Justice Department announced that the federal government would not interfere in the state’s experiment— that legal recreational sales began.

Business is booming. Cannabis sales in Colorado reached $700 million in 2014; by August 2015, that number was $100 million-plus every month. With about $70 million in tax revenue for fiscal 2015, marijuana brings in about twice the tax dollars that alcohol does.

And Colorado is a small state. In California, where only medicinal cannabis is legal, sales reached more than $1.2 billion in 2014. Plus, legal recreational use is spreading; recreational marijuana is legal in Colorado, Washington, Oregon, Alaska and the District of Columbia, and eight more states, including California, are expected to legalize it in 2016. The ArcView Group, a network of cannabis investors, estimates that if cannabis were legal nationally, it would be at least a $36 billion market.

Howard aims to corner the boutique niche of the market, but the goal is to do it best, not fastest. “We’re not in a rush to get bigger than our britches,” he says. In Colorado he plans three locations—Boulder, Denver and a ski resort town—and the goal is to have Shift either operating cannabis businesses or holding equity stakes in 15 states.

Howard isn’t a Boulder native. He was born in Denver in 1978; his father was an executive at travel company Cendant, his mother a homemaker at the time. His parents divorced in 1982, and in 1986 Howard and his mother, Cindy, moved to Casper, Wyo.—Cindy was marrying a man, Brad Cheney, who worked in sales for pharmaceutical firm Bristol-Myers Squibb. Howard’s mother got a job as a secretary, but the family—Howard would be joined by two half-brothers—struggled economically. “She tried night school,” Howard says, “but with work and taking care of me, she never completed it.”

With a population of about 50,000, Casper was a speck of a town, some 200 miles from the capital, Cheyenne. Its most prominent landmark is an old oil derrick. That didn’t matter much when Howard was a boy, but as a teenager he realized that there wasn’t a lot going on there. Though he occasionally went to the local country club to play golf with his stepfather, mostly Howard and his friends drank—30 packs of Keystone and Mickey’s malt liquor. The alcohol culture in town, Howard recalls, was “very aggressive.” When his friends and he went drinking out by the Alcova Reservoir south of town, the nights always seemed to end with a fight. Desperate for an alternative, Howard smoked pot for the first time when he was 16. “A friend said I should try it,” Howard recalls, “and it was fantastic. It really worked for me.” He still smokes almost every day, but now it’s to combat persistent neck pain from a youthful football injury and two car crashes.

Travis’ biological father, Steve Howard, still lived in Denver, and as soon as Travis and his friends could drive, they started making the 300-mile-each-way trip every chance they got—anything to get out of Casper. They’d stay in his father’s condo when he was traveling for work and go to hip-hop and punk concerts. Howard remembers one in particular: the 1996 Warped Tour, featuring alternative rock bands like the Mighty Mighty Bosstones, NOFX, Beck and Deftones, at Red Rocks, Denver’s famous natural amphitheater. “The cannabis scene was huge,” he says, and liberating. Hip-hop—Tupac, Dr. Dre, Biggie Smalls—had a similar appeal. “They were saying things that the establishment didn’t want you to say, talking about emotions that you were told not to feel.”

Howard wasn’t just clashing with authority in his own life; he was witnessing its impact upon others. When Travis was 6, Steve Howard had married a woman with a son named Tim, and despite the physical distance between them, Howard and his stepbrother grew close. In his early teens, Tim went through what Howard calls a “wild child” phase, and in ninth grade he was caught with a joint on his high school campus and promptly expelled. Never returning to school, he earned a GED at 19. “His life got trashed in ninth grade for having a joint,” Howard says. “Not that you should be having pot at a school— that’s very stupid—but…they threw him out. He couldn’t get student loans…It’s like, what the hell?” Tim, who is now 36, would struggle with alcohol abuse and do time in jail for a DUI. “He’s responsible for his choices,” Howard says. “I’m not going to blame someone else for his choices. But, damn, they didn’t even give a chance to educate him.”

The episode with Tim wasn’t the only time Howard saw people unfairly punished for smoking pot. When he was 16, Howard used to hang around the “bad” part of Casper, an area of low-income housing, trailer parks and a few basketball courts where most of the town’s black and Latino families lived. He and a few friends were playing basketball late one afternoon, and Howard and one of the other boys, who was black, were smoking a joint when a police car pulled up. The cops looked at Howard and told him to go home. Howard’s friend was issued a summons and later kicked off the high school football team. “That was the first time the music I had been listening to resonated with me that, Man, this is bullshit,” Howard says.

After finishing high school, Howard moved back to the Denver area. He studied business at Colorado State University and, in 2000, got a job in software at Sun Microsystems. He worked for three years before enrolling in the University of Colorado School of Law. In 2006, he began practicing business law, and the next year started his own practice. Howard sees practicing law as a logical extension of his youthful rebellion: “With that punk rock mentality came a desire to speak up for people who weren’t able to.” In 2009, the U.S. Justice Department issued a watershed policy paper, the Ogden Memorandum, that discouraged federal resources from being used for medical marijuana prosecution. Clients started asking Howard, one of very few business attorneys willing to represent cannabis entrepreneurs at the time, for help incorporating their cannabis businesses.

“You had people who were out-and-out criminals,” Howard says. But there were also “really good clients,” people who shared Howard’s belief that marijuana users were the subject of unfair prosecution and aimed to push the business into the mainstream. In 2010, Howard started Shift to provide business development services to cannabis companies. At the time, one of his legal clients was a longtime seller of medical marijuana named Reed Porter.

In 2010, Colorado mandated that dispensaries be vertically integrated with cannabis growers; the intention was to track cannabis “from seed to sale.” Porter had a lease on a building but needed help with permits. A business graduate of UC Boulder, Porter had been a partner at an organic food company called Jungle Foods; the company made flaxseed crackers that were sold nationally through Whole Foods. “He was approaching cannabis in a very different manner” than most of the state’s burgeoning entrepreneurs, who wanted to grow as much pot as possible as quickly as possible, Howard says. Porter “ just wanted to grow the best.”

“I thought the market lacked anything of quality, or even a concept of what quality was,” Reed Porter recalls.

“There was an abundance of new dispensaries opening up, and they were all subpar,” Porter says now. “I thought the market lacked anything of quality, or even a concept of what quality was.” The two men also shared the conviction that marijuana users were unfairly persecuted. Porter has two daughters; when they’re older, he says, he doesn’t want there to be “any more stigma” around cannabis. And if society’s most upstanding, successful citizens smoke pot, that stigma is harder to maintain.

The cannabis business was young, and much of the marijuana was raised by individual growers who cultivated their plants with tender loving care. “People were getting boutique-quality cannabis out of basements,” Howard says. “It was small batch, and it was phenomenal.” That was what Porter and Howard wanted to grow—“small batch, basement-love cannabis.” They just wanted to grow more of it.

Howard helped with the permitting, and soon Porter asked Howard to join as a partner. Howard was a “conservative attorney,” Porter explains. “He always said, ‘Let’s do this the right way.’” Together they launched Green Dream in August 2010. Howard would be the driving force behind the growth of the business, and Porter the agricultural brain.

Five years later, Green Dream has three “grows,” as they’re called, totaling 10,000 square feet, in strip malls and warehouses on the outskirts of Boulder. For small cannabis growers, 10,000 square feet of grow space typically produces between 250 and 500 pounds of marijuana per month, a tiny amount compared to the thousands of pounds per month of larger companies with acres under cultivation. But size inevitably means compromise: Large-scale cannabis operations use hydroponic systems to pump a standardized nutrient mix to plants in troughs. Green Dream’s plants, however, are divided among different rooms according to age and size, and receive a custom mix. “Every leaf and plant is different,” explains Spencer Fuller, Green Dream’s director of cultivation. Green Dream marijuana can smell like anything from grapes to citrus to diesel, and it has a healthy, well-tended appearance. The customized cultivation makes individual plants healthier and improves quality. It’s the difference between running a Christmas tree farm and growing a Bonsai tree.

Buyers approve. A reviewer for Westword, a Denver alt-weekly, had this to say of Green Dream: “Back in the day, there were fewer greater feelings…than finding a new connection. I hadn’t thought about that sensation in a while…But Green Dream…brought me back to those days.”

Cannabis is cultivated through cloning, but specific strains have been perfected through decades of breeding. Most important is the balance of two chemical compounds, THC, the psycho- active element in marijuana, and CBD, which has medically useful neurological effects. Green Dream’s high-THC strains—Bruce Banner #5, Moonshine Haze, Sour Diesel—will produce a powerful high, while others more often used in medical treatments—Charlotte’s Web—may have virtually no THC but high CBD. Medical strains are often used to treat cancer, chronic pain, epilepsy and loss of appetite from dis- eases such as Crohn’s or AIDS.

Fuller, who is in his early 30s and has Crohn’s disease, began growing cannabis when he was 12. He worked as a horticulturalist for the Denver Zoo before joining Shift in 2015. “I love being able to open a jar and feel my pride coming out of it with that smell,” he says.

When Fuller and his staff harvest the cannabis, they hang the branches upside down on drying racks in a room ventilated with giant fans. After the leaves have dried, the trimmers brush them away by hand, preserving a perfectly formed cannabis flower. (It’s a common misconception that the leaves of the cannabis plant are smoked; it’s actually the flower.) Large producers typically use machinery from the hops industry to automate the harvest, but the machines often mangle and contaminate flowers. Before a cannabis flower reaches a Green Dream customer, however, it has been handled and inspected by an expert at least three times. In the company’s small, tidy dispensary, a redbrick building that looks like a bank just down Look- out Road from the Boulder Country Club, Green Dream budtenders speak knowledgeably about the medicinal traits of the cannabis strains and the methods used to cultivate them. When marijuana was illegal, its smokers knew virtually nothing about where their pot was grown, who grew it, how it was cultivated and whether anything was added to it—like buying meat with no label. That’s still true for many large growers. By comparison, buying Green Dream cannabis is like reading the menu at Chez Panisse.

So far, the business plan is working. “What we’re doing in gross revenues surpasses people with 60,000 to 70,000 square feet” of grow space, Howard claims. In 2014, Green Dream had revenue of $5 million, and the company is growing by 25 percent annually. That pace should surge when Green Dream starts recreational sales in 2016. “Our metrics are killing it,” Howard says.

“I don’t think small scale is going to be around in a few years,” says the founder and CEO of cannabis company Rare Dankness, Scott Reach.

Not everyone is convinced that small but mighty is the way to go. One of the most ambitious cannabis entrepreneurs in Colorado is Scott Reach, the founder and CEO of cannabis company Rare Dankness. “I don’t think small scale is going to be around in a few years,” Reach says. He predicts that regulators will choke off the supply of state permits, forcing the surviving operators to boost production dramatically. Reach himself has secured some $10 million in credit from an anonymous Denver commercial real estate investor to remodel a warehouse on the city’s outskirts; he’s added a second floor, expanding it to 50,000 square feet total. To minimize labor costs, a computer will operate Reach’s hydroponics, HVAC and harvesting machinery. Most Rare Dankness cannabis will be machine-harvested and wholesaled to edibles manufacturers, but one-third will be sold as flowers to compete with boutique growers. Expecting that nationwide legalization is inevitable, Reach plans to open stores in Las Vegas, New York, Miami and either Los Angeles or San Francisco.

Several other companies are building national brands that will hit the market imminently. The biggest player is Privateer Holdings, which is launching a national brand dubbed Marley Natural—named, obviously, after the late Bob Marley. Privateer has raised $82 million to invest in cannabis businesses, mostly from family offices, ultra high net worth individuals and Founders Fund, the investment group of billionaire PayPal cofounder Peter Thiel. The $7 million alpha round for Privateer closed in 2013 and took two years to raise, according to CEO Brendan Kennedy; the next round of $75 million took just nine months. “Our investors come from the far left and the far right, politically,” Kennedy says. “Most of them are looking for a financial return, but they’re also looking for a social return from ending the harms caused by prohibition.”

Howard wants to focus more on connoisseurs than investors. With premium cannabis, he argues, he’s “attracting the people that can also help legitimize and normalize it.” And he can lead by example. “I can be well-spoken, educated and a citizen in my community, and talk about cannabis openly. I can also create tax revenue and profits, which in this society, sadly, is one of the only ways to normalize anything.” If social and financial elites come to consider cannabis a socially acceptable luxury product, won’t that start a cultural paradigm shift? “There are people in jail all over for this plant,” Howard says. “This is my power play.”

For more information on Green Dream and Shift Cannabis, contact cofounder Travis Howard: [email protected]. For more information on Rare Dankness, contact founder and CEO Scott Reach: [email protected].