In 2016, all the major stock indexes reached all-time highs, including the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500, the Nasdaq Composite and the Russell 2000. What’s more, several indexes posted double-digit returns, including the Dow, S&P and the Russell 2000, which returned 21.31 percent last year.1

Despite the stellar year for stocks, most well-diversified portfolios did not keep up with the returns seen by the all-equity indexes, due to exposure to the fixed-income market, which has nosedived since the election.

Nevertheless, now is not the time to second-guess your long-term investment plan. Instead, it’s actually a good time to remind yourself of why you embarked on your long-term investment strategy in the first place—to help meet your daily needs and long-term goals.

Here’s why we believe it’s important to tune out the financial “noise” and stay focused on your long-term investment plan.

Not all markets went up. While the equity markets, by and large, posted double-digit gains last year, not all asset classes went up. In fact, many asset classes have declined in value since the election on November 8. For example, Treasury, municipal, corporate and emerging-market bonds all have been declining, in addition to international and emerging-market stocks.

Many domestic equity industries, including consumer staples, utilities, REITs, telecom and technology, declined in late 2016, as well. This may have impacted your investments, as a well-diversified portfolio most likely has an allocation to these asset classes, which has hurt returns.

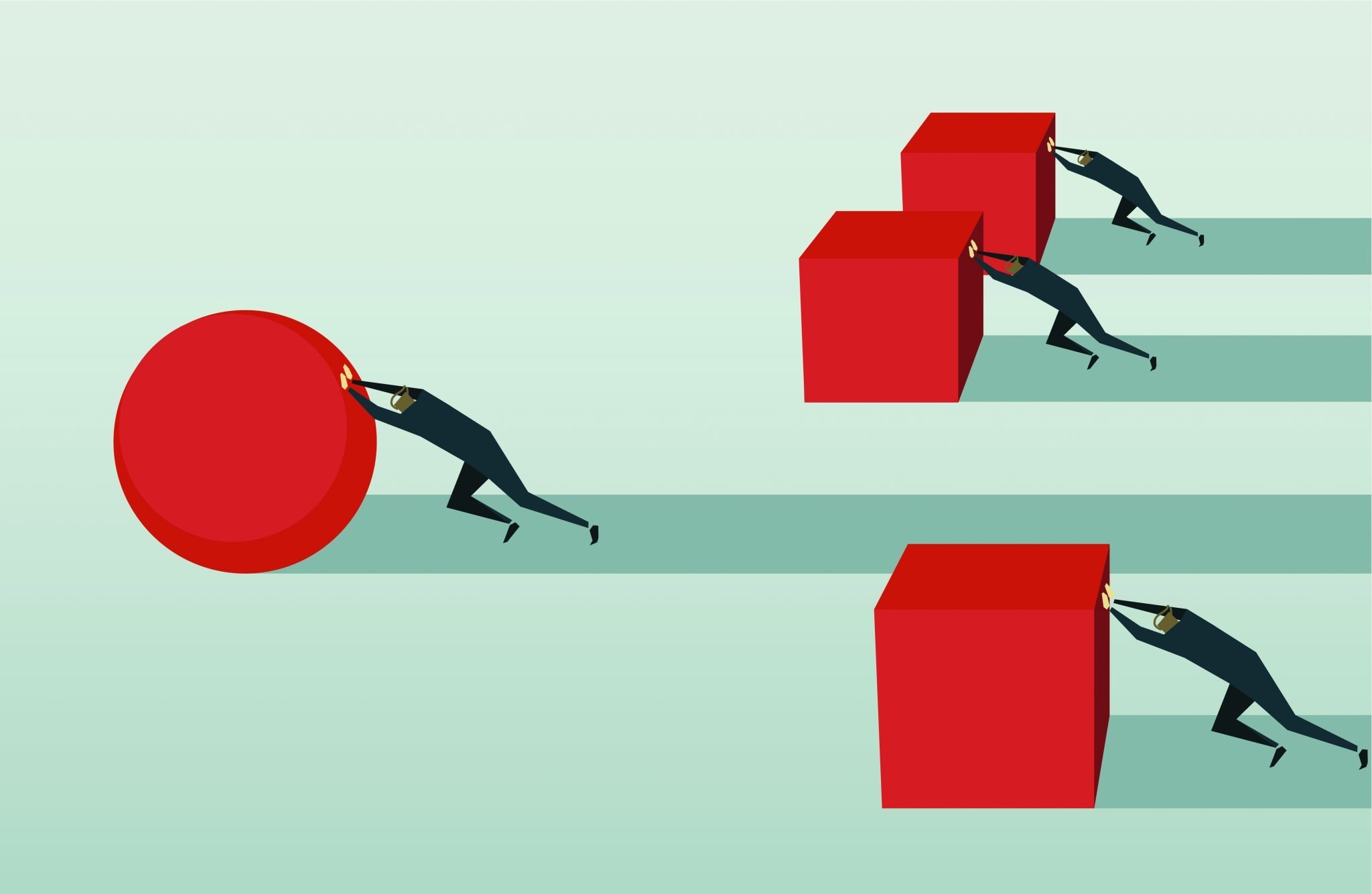

It’s important to remember that a portfolio composed entirely of stocks will generate a higher return during a bull market than a portfolio composed of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds, or a 100 percent bond portfolio. However, a diversified portfolio will be less volatile than a portfolio containing all stocks. So, while you may not be gaining in lockstep with the overall equity market, you are, regardless, shielding your portfolio from significant losses in the event of a major downturn or market correction.

An asset-allocation strategy can help you grow your investments without exposing you to unnecessary risk.

The market is nearly impossible to time.

There’s quite a bit of evidence showing the negative impact of trying to time the market to investor portfolios. One report, from research firm DALBAR, found that the average equity investor underperformed the broader stockmarket over a 30-year period, with an average annual return of about 3.66 percent per year, versus the S&P 500’s 10.3 percent return.2

This underperformance has been the result of bad market timing, as investors have sought to buy low and sell high, but have often done the opposite. That’s because investors often buy or sell when everyone else is doing thesame. As a result investors end up buying stocks at a higher price than they would have, had they bought based on the company’s fundamentals or other factors, as opposed to when the market was going up or down.

There’s a reason you created a long-term investment strategy. An effective asset-allocation strategy can help you grow your investments without exposing you to unnecessary risk. While it may be tempting to rebalance in the wake of the recent market performance, remember that market rallies and downturns can happen very quickly. Switching your asset allocation during the back half of a bull market might cause you to pursue stocks that are overvalued, and therefore poised to go down in the event of a market correction.

Key takeaway. There are winners and losers in every market, as some assets gain during periods when others decline. It’s important to tune out the noise and sharpen your long-term perspective, which we believe is the best way to navigate volatile markets.

1FactSet

2Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior study, DALBAR, April 2016.

Information expressed herein is strictly the opinion of Kayne Anderson Rudnick and is provided for discussion purposes only. This report should not be considered a recommendation or solicitation to purchase securities. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This article was originally published in the February–April 2017 issue of Worth.