Private foundations are an ingrained part of American philanthropic history that goes back to the days of industry giants like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockfeller.

Today, there are approximately 100,000 U.S. foundations, which have distributed over $56 billion. While these private foundations typically receive little media attention, several have recently garnered unwanted news coverage for questionable practices or conflicts of interests.

The following are a few areas of risk to consider when establishing and managing a private foundation. Because of the legal complexities involved, this list is in no way comprehensive. Foundation leaders should always consult professionals when assessing or addressing foundation management risks.

DEADLINES

A common pitfall foundations face is the failure to comply with federal and state regulatory reporting requirements. Even though the foundation may be exempt from federal income tax, there are still requirements to file financial information to the Internal Revenue Service and submit an annual filing with the state’s regulatory agency.

There may also be filing requirements related to paid staff, and professional or trustee fees. Failure to meet these deadlines can result in serious delinquency fees.

LIABILITIES

An area that gets overlooked is sufficient insurance coverage against liability risks. Consider budgeting for insurance expenses up-front. Foundations with board members should also consider a directors and officers policy against personal liability if lawsuits are brought against the foundation. This is especially important if you plan to or have employed staff.

DISTRIBUTIONS

Most foundations understand that one of the key requirements when they register for private foundation status is that they must distribute, at a minimum, 5 percent of the fair market value of their assets each year (Section 4942 of the Internal Revenue Code).

As simple as this requirement first appears, it is a cause of a large number of complications. In some cases, foundations struggle with how to accurately calculate the requirement. In other cases, foundations may be unsure how to properly report grant distributions or how to determine if certain expenses may be included as part of the asset distribution.

Failure to distribute the minimum requirement by the end of the subsequent fiscal year can result in a 30 percent excise tax on the undistributed amount and an additional 100 percent excise tax if the required amounts remain undistributed.

SELF-DEALING

Unquestionably, one of the largest pitfalls, and most complex areas of risk, is self-dealing and conflicts of interest for private foundation boards. Rules prohibit any direct or indirect financial transactions between the foundation and “disqualified persons,” which includes directors or trustees, family members, managers and substantial contributors, to name a few.

In general, “disqualified persons” include any parties that are closely related to the foundation; these can include individuals as well as corporations, partnerships or trusts. For example, a private foundation might host a fund-raising event at a facility owned by a foundation board member who charges a discounted rental fee. Despite the good intentions of the board member, this is considered self-dealing.

Other common examples of self-dealing may include: excessive compensation to board or family members, payment for expenses deemed unreasonable or unnecessary, the purchase of tickets to a fund-raising event using foundation funds, use of shared office space and the sharing of costs with the family business or the award of grants to public charities where a foundation member sits on the public charity board… just to name a few.

To make matters more complex, there are many exceptions to the rules, to permit certain activities. Transactions with “disqualified persons” may be permissible if they are reasonable and necessary to carry out the exempt purposes of the foundation.

For example, self-dealing doesn’t occur if a foundation leader attends a fund-raising event as a reasonable and necessary part of her foundation duties (grantee oversight, evaluation, etc.). Penalties for self-dealing include a 10 percent tax of the amount involved in the self-dealing and an additional 5 percent tax against the foundation manager.

CONCLUSION

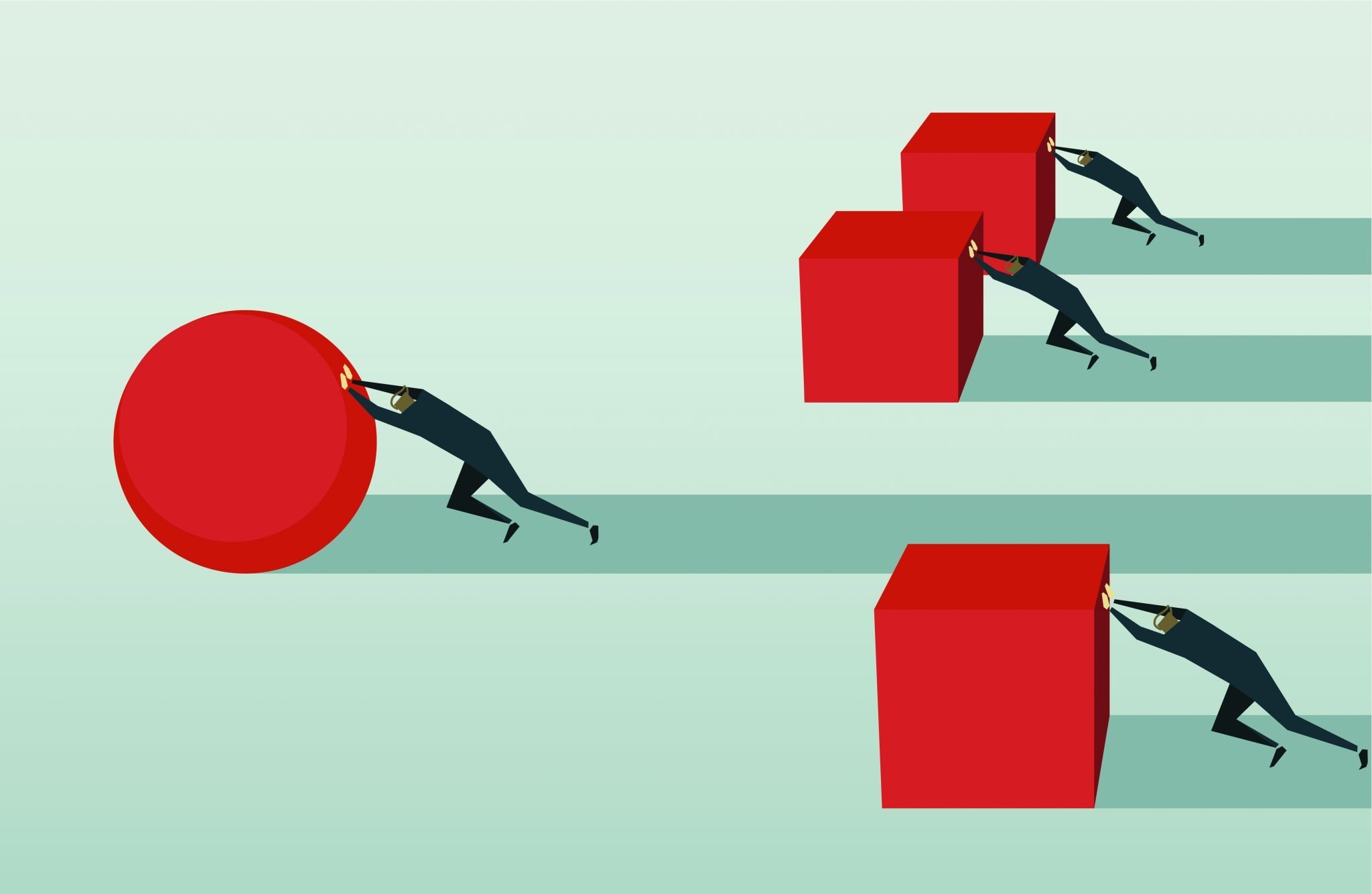

Your desire to establish a private foundation may come from a deeply felt motivation to use your wealth to make a social impact and create a legacy. And in this regard, you will be following in the hallowed tradition of Carnegie and Rockefeller.

But do not jeopardize your foundation’s reputation and philanthropic goals by falling into one of the common pitfalls and risks of managing your foundation. By investing resources up-front to establish a risk-management program, and by leveraging professional foundation management advice, you can avoid the potential of larger financial and reputational costs later.