From the June 1999 issue: “Why Billionaires Should Be Outlawed” is a fun, if flawed, feature by David Sheff that argues why there should be fewer billionaires. In 1999 billionaires were a growing group, and projections showed many more being made. Today, those projections are right on schedule, and the arguments made hit close to home.

This is part one of a two-part series. Click here for part 2.

Howard Hughes—the mogul, entrepreneur and inventor—was psychotic and drugged, dying in Mexico. Flipping through a newspaper, he came across an item in which he was referred to as a “paranoid, deranged millionaire.” “I am not a millionaire,” Hughes raved to his coterie of retainers. “I’m a billionaire.”

Hughes knew that the distinction was more than a ninth zero.

Hughes was a member of the most exclusive Ninth Zero Club. “I answer to no one, can do what I want, and wield more power than presidents, whose authority is limited and tenure is brief,” he once said.

Howard Hughes. Illustration by David Plunkert

Howard Hughes. Illustration by David Plunkert

More recently, another club member, George Soros, went further: “It is a sort of disease when you consider yourself some kind of god, the creator of everything, but I feel comfortable about it now since I began to live it out.”

Soros has lived it out in remarkable ways. Back in 1993, well before the Serbians waged war on Kosovo, they were in Sarajevo, committing a similar campaign of ethnic cleansing. Soros grew frustrated when Western aid to the war-torn region was tied up in red tape and politics. Since Bosnia was economically and strategically unimportant to the U.S., America stayed away from the conflict that was slaughtering tens of thousands of civilians.

In Sarajevo, the Serbs had severed all of the water lines leading into the center of the city. That meant Sarajevans were forced to travel on foot across the city to the one existing small water supply. While waiting in line or lugging buckets to their homes, people were easy targets for snipers. Indeed, many of the civilians who were maimed or killed in Sarajevo during that period were collecting water.

Reading the details (had they been published) in the New York Times or another newspaper, most of us would have shaken our heads in disgust and said, silently or aloud, “Someone should do something.” Soros did.

He hired the well-known international relief worker Fred Cuny (who later disappeared in Chechnya) to create an alternative water system for Sarajevo. Cuny brought in engineers to design an emergency treatment plant, which was constructed in Texas. It included boxcar-sized water filters that were loaded onto C-130 cargo aircraft. The massive tanks and filters were made with built-in wheels and jacks, designed so that they could be unloaded from the planes within ten minutes, the maximum amount of time a UN relief plane was permitted to stay on the ground in Sarajevo.

While that treatment plant was being set up in a seldom-used highway tunnel on the outskirts of the city, Soros’s operation brought in a second water-purification system for a location above Sarajevo. Since this second one would be more vulnerable to Serb mortar fire, the team covered it with a barrier made of steel rails and concrete panels that were in turn covered with earth and junked cars—to absorb the artillery fire.

By August 1994, water flowed from the systems. According to the mayor of Sarajevo, an incalculable number of lives were saved. “The water kept Sarajevo alive,” he later said. The cost? For Soros, pocket change: $50 million.

In 1948, there was one American billionaire, Henry Ford. John D. Rockefeller had hundreds of millions of dollars, but not a billion. It took until the 1970s before there were more than ten billionaires in this country. By 1980, however, there were 94, and now there are close to 200—the exact number fluctuating with stock markets, exchange rates and other economic indexes.

Whereas a million dollars was once the prize that was out of reach of all but a few, millionaires are now a dime a dozen, or almost: There are 3.5 million in America. While tens and hundreds of millions of dollars still impress, the mark of ultimate success today is the ninth zero. Inevitably, the next milestones will be the 10th and 11th, the world’s first centi-billionaire and, soon enough, trillionaire. (Bill or Warren? The sultan of Brunei? The race has become something of a spectator sport.)

The members of the Ninth Zero Club are an eclectic, eccentric group who are both well known and unknown. Eight of the richest 10 Americans in 1982 were oil billionaires, but last year, four of the five wealthiest U.S. citizens made their fortunes in computers and software (three were Microsoft billionaires, and Michael Dell was number four).

We have also just witnessed the emergence of the world’s first Internet billionaires: Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos, America Online’s Steve Case and Yahoo’s Jerry Yang and David Filo. Still, the billionaires come from many fields of human endeavor, from entertainment (George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, David Geffen, etc.) to french fries (John Simplot, who, before he got richer on microchips, earned his first fortune on the potatoes used by McDonald’s). There are still oil billionaires, real-estate tycoons, and a number of others who made their money in money itself, investors in everything from stocks to silver.

There’s lots of jockeying for position. A few years ago, Warren Buffett was the seventh-richest American but leaped to number two in two years when his stock portfolio nearly doubled, his net worth increasing to $15 billion from $7.9 billion. (He’s now worth $29 billion in 1999.) Donald Trump, whose fortune slipped to negative $900 million in 1990, returned to the club in 1997 with $1.4 billion. America’s richest human, Baron Gates, was already at the top of the list before his worth increased by almost 50 percent last year. With $58 billion, he is no longer only America’s richest but the world’s. (The sultan of Brunei, in second place, has $36 billion.)

The next milestone will be the world’s first centi-billionaire. Bill or Warren? The sultan of Brunei? The race has become something of a spectator sport.

Billionaires fit generally into two categories: those who inherited their fortunes and those who made them. Indeed, the club is crowded by family members, including five Waltons (each with $11 billion), plus assorted Fishers, Haases, Johnsons, Mellons and, of course, Rockefellers.

There are occasional rags-to-riches stories among the club members, though few rags-to-riches stories turn out this rich. More often, billionaires came from middle- or upper-middle-class backgrounds. Some built fortunes after false starts (before Hewlett-Packard became successful, Stanford University buddies Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard tried to sell a bowling-alley foul-line indicator, a weight-reduction machine and an electronic harmonica tuner). Though a few were Midases: Whatever they touched turned to gold (Buffett, for one). Some pushed their inventions, and others created art that succeeded on an outrageous scale (Star Wars). Some worked maniacally to prove their worth to their parents; others, to offer a better life to their children. Some had what appeared to be a simple and unambiguous goal: to be rich. Can an employee become a billionaire? The last nonfounder or heir to hit the list was the late Roberto Goizueta, who, after working for Coca-Cola for 43 years and eventually becoming its CEO, amassed a $1.3 billion fortune.

Make no mistake: A billion dollars is a lot of money. It’s unfathomable, as easy to conceive of as, say, alternative dimensions. One would not be able to acquire a major corporation for a single billion dollars, but a billion will buy just about anything else (including, of course, the assets of 1,000 millionaires).

A billionaire, in fact, could buy one each of his class’ favorite toys, top of the line, and barely dent his or her pocketbook. (Do the math: A twin-jet Gulfstream GV + a 170-foot yacht with six to eight state rooms + an eight-passenger Bell Boeing 609 tilt-rotor helicopter + the world’s most expensive production car, a Bentley Azure + the priciest wristwatch, an Abraham-Louis Breguet = less than $100 million.)

SunAmerica’s Eli Broad charged a Roy Lichtenstein painting on his American Express card for the thrill of earning 2.5 million frequent-flier miles. Richard Branson bought himself an island. So did Ted Turner.

Even billionaires’ most expensive possessions—their homes—hardly make a dip in their billion(s). To wit: Oracle founder Larry Ellison’s retreat, built in the style of a 16th-century Japanese imperial residence, cost about $40 million. (He has $4.9 billion.) David Geffen’s mansion has an imported wood floor said to be the one on which Napoleon proposed to Josephine, and 114 bedrooms and 132 bathrooms (the Los Angeles Times once described him “padding around in his hopelessly large house, like some mid-life version of Kevin from Home Alone”). It cost $47.5 million. (He’s worth $2.5 billion.) William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon cost him $10 million, mostly in depression dollars (about $93 million, adjusted for inflation). And Bill Gates’ high-tech palace is cheap by comparison at $60 million.

Billionaires are apparently compelled to buy professional sports teams. But these cost a mere $200 million or so. So who needs a billion dollars?

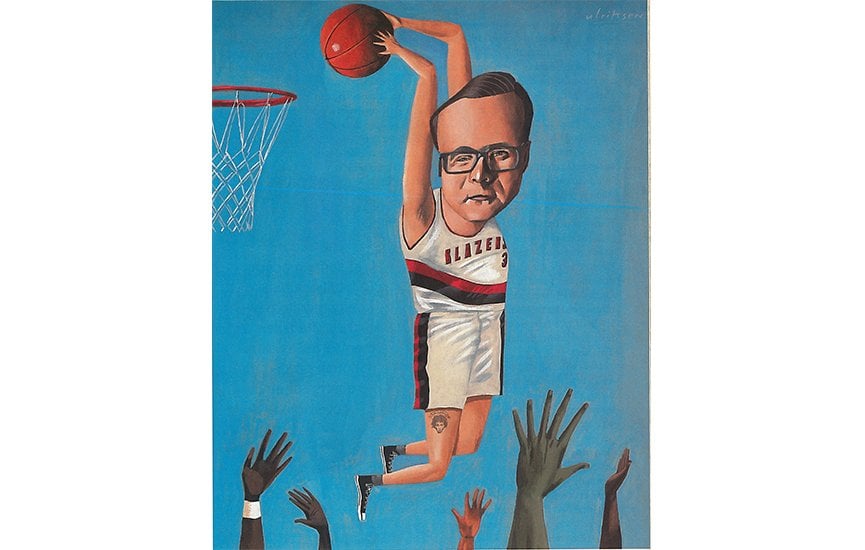

Billionaires occasionally pay for museums and theaters, writing off the contributions, but their biggest gifts are in the low millions. They fork out more millions for personal passions, such as Ed Bass’s $150 million Biosphere 2, the flawed 3.5-acre self-contained ecosystem in Arizona (last year bequeathed to Columbia University) and Paul Allen’s $60 million Experience Music Project (basically a Jimi Hendrix museum).

NBA Portland Trailblazers owner Paul Allen. Illustration by David Plunkert

NBA Portland Trailblazers owner Paul Allen. Illustration by David Plunkert

In addition, they are apparently compelled to buy professional sports teams. (Allen, Buffett, Philip Anschutz, Hiroshi Yamauchi, Craig McCaw, Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch each have at least one.) But these also are investments and cost a mere $200 million or so—the price Allen paid for the Seattle Seahawks. Does anyone need his own sports team? Even if the answer is sure, why not, a multimillionaire can afford one. So who needs a billion dollars?

It leads to a bigger question that may seem, on its face, heretical and un-American. Should anyone have that much money—and the power that comes with it? The answer, in my estimation, is unequivocal. No. Absolutely not. For five very good reasons….

Part 2 of this two-part series will discuss the reasons why billionaires should be outlawed.

David Sheff, author of Game Over (Random House), is currently writing a book about the Internet in China

Reprinted from the June 1999 issue of Worth

Part two of this two-part series.