In the February-March 2012 issue Worth featured this Q&A with short seller and Muddy Waters founder Carson Block. At the time, he had just uncovered fraud in publicly traded Chinese companies, and since then, he has seen a number of company stocks plunge as a result of his reports. Read how, as editor in chief Richard Bradley said in his piece, Block notoriously “rose from being a high school troublemaker to a Wall Street troublemaker.”

In June 2011 a little-known equity research firm named Muddy Waters Research published a report on a Chinese timber company called Sino-Forest. Muddy Waters charged that the firm, which was listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, was a Ponzi scheme. Within days Sino-Forest’s stock price plummeted, devastating the company’s single largest shareholder, hedge fund manager John Paulson, who quickly dumped his fund’s 34.7 million shares at a paper loss of a reported $720 million.

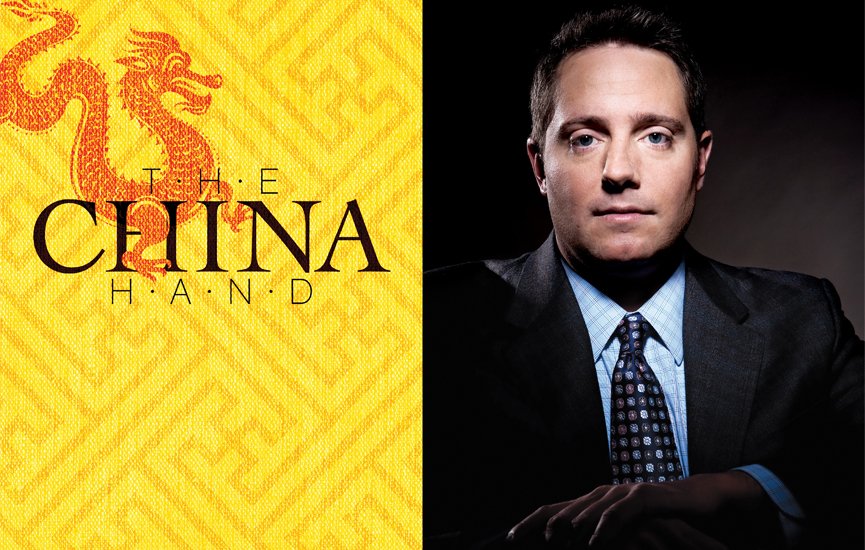

Muddy Waters’ founder, a 35-year-old University of Southern California graduate named Carson Block, is an unlikely Wall Street power broker. For one thing, he’s never worked on Wall Street. For another, he doesn’t think much of Wall Street, particularly the conflicts of interest he sees in much of investment banking. Instead, Block began his career with a youthful interest in Asia and a father who analyzed stocks for a living. Two decades later, Carson Block has become one of finance’s most influential voices when it comes to the Chinese economy—a subject of no small import to the rest of the world.

He is also a controversial voice. Because of his unorthodox background, contrarian positions and colorful speaking style, Block has made enemies. He’s cost some of them money; others just don’t seem to approve of his outsider style. Either way, they accuse Block of being an untrustworthy, self-interested market manipulator—even as Block’s critical analyses of Chinese companies repeatedly prove accurate.

Over the course of two multi-hour interviews with Worth, Block spoke candidly about himself and investing in China. He declined to talk about only two things: his Chinese employees, whose ability to continue working for him he did not want to jeopardize, and the location of his firm. Otherwise, Block happily confessed that he generally enjoys stirring the pot. “I have always taken some pleasure,” he says, “in being a bit of a pain in the ass.”

You’ve asked that I keep your location secret. Why?

Better safe than sorry. What worries me most is an American investor who’s lost money and blames me. I spoke at a conference recently, and somebody there expressed so much hostility about me to someone else that they had security remove the guy.

Okay, let’s start with something you can talk about. Where did you grow up?

In suburban New Jersey, split between Summit and Chatham—my parents were divorced. But I would also say that I grew up in the investment banking industry. My father was a sell-side analyst who generated his own research ideas. Around the time I was 15, I took an interest in emerging markets. I thought they were the investing opportunity of my generation.

That’s when you got interested in Asia?

My first day of high school, a history teacher talked about a program in which he’d take students to Japan for a summer. As soon as class was over, I ran up to him—”What are the requirements?” I didn’t know they’d pretty much take any kid who wanted to go.

Pretty mature for a high school kid…

Academically, I was an underachiever. My grades were average, and I was one of the bigger partiers in the school. Every Friday and Saturday night, I was the guy hosting the parties. I had problems with authority—I set the record for detentions in my elementary school.

Where did that rebellion come from?

From my father, who’s pretty irreverent. He’s a polio survivor. He’s 73 now, and until three years ago he was playing squash. Then at age 70 he became a licensed spin instructor.

But even as a high schooler you were interested in finance?

One of my high school classmates was one of Jon Corzine’s sons, and I went to see Mr. Corzine at his office at Goldman, where he was chair and CEO, to talk to him about a career on Wall Street. He said to me, “I wish my son were as serious as you are, really buckling down in school.” I said, “Mr. Corzine, I am very serious about my career, but I just want to set the record straight—I’m basically a 2.7 student.”

USC, where you went to college, has a reputation as a party school. Is that why you went there?

I was actually leaning toward Tulane until I realized that USC would be a far better place to meet people from Asia. It turned out to be true. My roommate and best friend from college is from Taiwan, and I spent a lot of time hanging out with Taiwanese students. Then I studied in Beijing in the summer of ’97, just before my senior year, and I formed this idea that I might want to open up an equity research firm in China after I graduated.

What gave you the idea?

At the time, Chinese stock markets were purely speculative; the vast majority of Chinese were terrified of the markets and would not put their money in. I thought, if we can bring a systematic way of investing to China, there’ll be demand for the research part.

How did that work out?

My father lent me money to go to China after college. As soon as I got there, I started to network. At the time—this was 1998—you had far fewer Westerners there. I was perceived as this well-educated young guy, who, relative to most Chinese, might have some money behind me. So I got some access and met a lot of interesting people.

What was your goal?

I was looking for at least five stocks that I could consider investable.

And?

And I couldn’t for the life of me find any companies I was excited about.

Why not?

It was a reflection of the state of disclosures. Chinese companies were so opaque that after about six months I just threw up my hands.

Block returned to the United States and took a job with wholesale bank CIBC World Markets, only to find that working at a big firm wasn’t “a good fit.” As he says now, “I harbored this illusion…that if I went to a big bank, people would actually care about my opinions.” In 2002 Block started law school at the Chicago-Kent College of Law “to fill in some of [my] blanks.” After graduation he took a job in Shanghai with the law firm Jones Day, helping to put together foreign investment deals.

What were your feelings about China when you returned in 2005?

I saw tremendous potential in the country and the people. But I had a real innocence in my view of how China worked.

Which is in a way what led you into entrepreneurship, right?

I left Jones Day in December 2006 to start a wealth management firm based in Singapore that would manage the offshore assets of wealthy Chinese families. In China, this is a gray area. It’s accepted that most wealthy people have liquid assets offshore, but it’s not necessarily legal for them to do so.

During that time you cowrote Doing Business in China for Dummies. Were you really qualified for that?

Parts of the subject I knew pretty well, having practiced law there. But much of the book entailed going out and interviewing people, which helped me develop a great network.

You also helped start a self-storage business called Love Box Self Storage.

A friend of mine approached me and said he was going to start mainland China’s first real self-storage firm. I said, “I’ll help you get it off the ground.” We marketed it as a near-luxury service. The idea was that everybody’s aspiring to this improved lifestyle, so we pitched the idea that part and parcel of a happy Western lifestyle is having self-storage, which gives you flexibility to buy more goods without cluttering up your home. I thought it could be big.

Why the name Love Box?

I have a filthy sense of humor.

Love Box is still in business, but it wasn’t exactly a smooth ride.

I made a lot of mistakes that only someone who comes from finance or legal could make—things did not go according to the model. Everything was a struggle.

What did that experience teach you?

That there’s a lot more to doing business in China than meets the eye.

Such as?

I was close to every transaction the business made, from dealing with construction contractors to buying toner for the printer. With a lot of vendors, one of the worst things you could do was pay your bill in full. If you paid your bill in full, they figured you were stupid. If you weren’t constantly checking on what they were doing, a lot of the people who did business with foreigners came to regard you as stupid.

Was corruption a problem?

My Chinese employees were constantly offered kickbacks. And we saw how employees, from the lowest level to the top, would run shadow businesses inside their employers’ companies, taking company assets and using them for themselves.

So what was the moral of the Love Box story?

That you’re in a business environment that is far more bare-knuckle than the United States. You cannot depend on the legal system to enforce your rights. And you’re also dealing with people who grew up poor, who are desperate to earn money. Well, not to earn money, to get it. I have a code of ethics, and I wasn’t willing to double-cross, to pay kickbacks, to pay bribes.

That’s strong language. Do critics ever accuse you of being racist?

Among the companies that we expose, that’s become a common refrain. I don’t react to that. I’ve given interviews to Chinese media face-to-face, and the reporters there get clearly that that’s not what I’m about.

Still, it sounds as if you’re portraying an entire culture as corrupt.

Actually, my impression is that a lot of Chinese are sick of this. They look around and see their companies being looted by the top guy and the people right underneath him. But they also worry, “If I don’t start taking what I can get, what’s going to be left for me?”

I saw a tremendous potential in the country and the people. But I had a real innocence of how China worked.

How did you start Muddy Waters?

It was a complete accident. Toward the end of 2009 my father got excited about micro-cap Chinese companies listed in the U.S. He had a number of names he wanted me to check out. One of the companies was called Orient Paper. I agreed to take a look.

I went back to China at the beginning of 2010 to visit the company and brought a friend with expertise in manufacturing. We started reading Orient’s filings, and we saw telltale signs of graft—revenue growing at 35 to 40 percent a year even though the top customers were constantly changing. How could you be losing your top customers and still be growing your top line 35 to 40 percent a year?

So what happened when you visited the factory?

As soon as we walked in, my friend said to me, “Oh my God, we’ve got ’em.”

What did you see?

Equipment they carried on the balance sheet for $60 million was scrap equipment that would maybe fetch $2 million. The company was about to claim that for 2009 it did a little over $100 million in revenue. There was no way this equipment could support that level of production.

And how did that lead you to start the firm?

We had a report ready to go by the end of June. A few days earlier, I had set up Muddy Waters, LLC. I had a mailing list of maybe 50 guys in the investment industry with whom I occasionally spoke, so I sent the report out into the ether.

What reaction did you expect?

Maybe the stock would trade down a point or so and start a longer-term examination of this company.

What reaction did you get?

The report went viral, and within 48 hours the stock was down 55 percent.

That must have been gratifying.

I actually thought, “Oh my God, there’s gonna be retaliation for this.”

Like what?

Physical retaliation, because I was still in China. Lawsuits. Everybody slandering me. The first two have not yet happened; the last one turned out to be correct.

What happened next?

A lot of hedge funds had been suspecting that many of these Chinese companies were frauds, but nobody had proven it. People began helping me connect the dots, emailing me and saying, “I’ve been investing in these companies for years, and I have to tell you this is a massive systemic problem. Let’s talk.”

Your critics charge that because you short the companies you research, your reports can’t be trusted.

Politics show that ad hominem attacks are actually pretty effective, even when they have nothing to do with substance.

Short or not, you must take some satisfaction in seeing your work have an impact.

Sometimes it’s easy to focus on the wrong thing, to look at the [investing] message boards and see yourself being maligned as a charlatan. But there are a lot of people out there who give credence to the work we do. That’s a great feeling—after all these years of being a wiseass, finally someone takes you seriously.

When we’re dealing with people whom we suspect are liars, we can’t go in through the front door.

Muddy Waters published its next report, on a water-treatment firm called RINO International, in November 2010.

We called some of RINO’s purported customers and found out that they were not actually customers. But what ultimately sealed this thing as a victory was our analysis of RINO’s purported tax rates and tax treatment—we did some really sophisticated accounting analysis.

How did RINO respond to your charges that the company was forging contracts and top employees were embezzling millions?

RINO scheduled a conference call, and then just before it was going to start, the operator came on the line and cancelled it. The company [later] admitted that it committed fraud—we got it right. So that really boosted our reputation.

The Sino-Forest report, which you published in June 2011, brought you the most publicity of your career. What convinced you that the company was bogus?

Sino-Forest had been around for so long—17 years—that there was this massive paper trail. We pulled about 100 SAIC [State Administration for Industry and Commerce] files. When you have 100 files that you’d have to scrub, it’s impossible to really clean it up. Although I don’t know if they ever tried.

What did you find in those files?

Every two or three days would yield a smoking gun. At the end, it was definitely not challenging to piece together what was going on.

It was challenging to John Paulson, whose hedge fund lost several hundred million dollars after your report came out.

To be fair to Paulson, his investment was a lot smaller—it had grown. I blame the sell-side analysts more. Sino-Forest was a big potential banking client, and that overrode whatever internal doubts the banks had.

Did you ever talk to Paulson?

I can’t comment on that. It’s a little too sensitive.

For whom?

Not for me.

How does the Chinese government feel about your work?

I can’t speak for the Chinese government—they’re busy running a country. But so long as they are not taking measures to stop us, I have to assume that they do not condone the listing of frauds on overseas exchanges.

You’re more worried about Americans?

I don’t like to let people know what I do when I first meet them; I only want people whom I trust to know that information, because I do have a worry about somebody who’s unhinged.

That sounds stressful.

There are a lot of people who, for business advantage, are trying to get information on Muddy Waters, on me. I’m very careful about speaking on mobile phones—they could be intercepted. There are people who will go to some length to learn about what we’re doing.

Let’s talk about technique. How was Muddy Waters able to find these financial frauds when so many other analysts did not?

We are not MBAs who sit around and look at spreadsheets all day. We have diverse skills—finance people, accountants, entrepreneurs, lawyers, technology and Internet experts. So we can look at a company from all these perspectives and come up with a much more solid understanding than your average analyst.

But you and other Muddy Waters employees have also been charged with misrepresenting yourselves.

When we’re dealing with people whom we suspect are liars, we can’t go in through the front door to talk to them about their business, because they lie to us. So we often approach the company as a potential client.

So there’s some undercover detective work.

A pretty decent bit of that, yes.

After seeing so much corruption, do you still like China?

I have a lot of dear friends who are Chinese, and I always look forward to seeing them. But I don’t feel positively about the direction of the standard of living in China. Household incomes may be going up, but the standard of living is going down.

What makes you say that?

Environmental issues are massive. The air pollution, the water pollution…It takes a toll. You don’t feel great about the food that you eat.

One of the things that people don’t understand is that if you’re Chinese, you’re born into the most competitive society on the planet. You’re competing from day one for school spots, for jobs, for money in a country that’s still largely poor. People have a hard time turning that off when they step outside of the workplace. That competitiveness affects their happiness.

So the idea that Americans need to start learning from the Chinese is a fallacy?

I do admire the way the Chinese value education. When you see how people are really willing to learn—that’s something that we should emulate.

And how does having lived in China make you feel about U.S. culture?

I moved back to the U.S. in November 2010. Shortly after, I went to a football game at USC, the first game I’d attended in a few years. The stadium was packed—90,000 people. It struck me that you have 90,000 people who have come together just to cheer and have a good time. And you don’t get that in China. You don’t have an emphasis on this culture where people can come together and connect.

You’ve also warned that the Chinese economy is a bubble.

I first called it a fixed asset bubble in late 2008. My prediction was that it would pop within two to five years. I think we’re on track—it’ll pop within two to three years from now.

And the impact globally?

We could be looking at a situation where equity markets in developed countries such as the U.S. and developing markets are lower five to 10 years from now than they are today.

So what do you invest in?

I began buying gold aggressively back in 2002, and that obviously was a very good investment. Now, most of my capital is in cash on the sideline. There will be opportunities when the dust settles.