In 1998, healthcare provider Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control published a paper showing that adults who had experienced extreme stress as children were at higher risk for developing life-threatening illnesses—such as cancer and heart disease—than adults whose childhood was comparatively stress-free. The more adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, a child lived through, the greater the odds of chronic illness down the road.

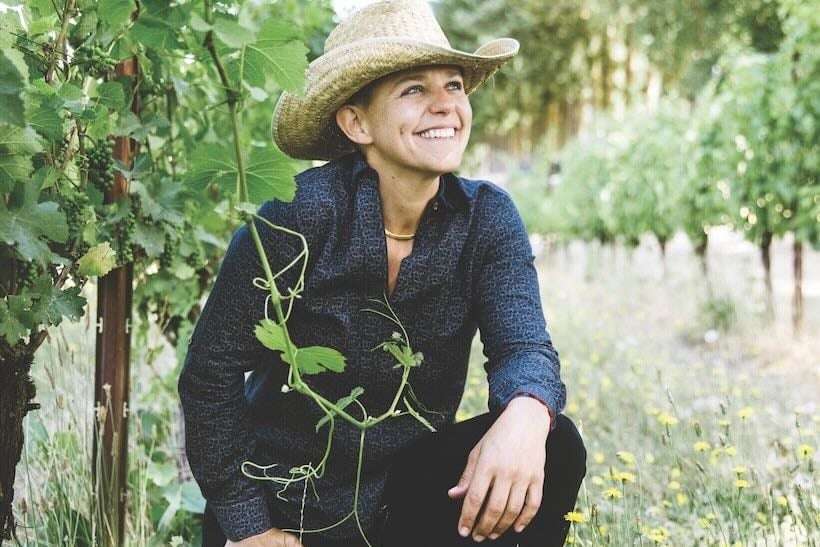

For California-based physician Nadine Burke Harris, the study was an epiphany: It confirmed her hunch that emotional damage in childhood could effect profound physiological damage later in life. Once a pediatrician in San Francisco’s then-impoverished Mission District, Burke Harris founded that city’s Center for Youth Wellness, a pediatric research clinic, in 2007. She and her team study childhood trauma and aim to reverse the long-term physical harm that stress can inflict upon the body. “Doctors may be afraid that by asking questions about emotional trauma they’ll open Pandora’s box,” Burke Harris says. “But not asking is fundamentally harmful.”

Burke Harris has since developed a methodology for doctors to screen for ACEs and partnered with six treatment centers across the country to help patients reverse the damage. She details this journey and the challenges for ACE research in her powerful book, The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity. In the following excerpt, Burke Harris explains the inspiration for her work and the effect stress has on the body.

—Sarah Grant

It was chilly, which was typical for a December night in San Francisco, and as I walked down Mission Street with my friends, I hugged myself to try to warm up. The four of us talked simultaneously, our voices drowning out the sounds of the city as we made our way back to the car. Not wanting to part ways as the evening came to an end, we lingered on the corner of 19th and Mission. None of us noticed a red car slowing down across the street. Seconds later, we heard pop! pop! pop!

As the car peeled out toward 20th Street, my friend Michael tried to laugh it off.

“It’s just some stupid kids playing with firecrackers,” he said. But a few moments later, he got uneasy and ushered us toward his car. “We gotta get out of here. Something’s going down.”

We were almost at Michael’s vehicle when we saw the man lying on the sidewalk.

“Oh my God,” my cousin Jackii cried, “he’s been shot!”

Reflexively, I headed toward the victim, not noticing that my friends were running in the opposite direction. “Nadine!” Michael said. He grabbed at my arm, but too late.

I dropped to my knees when I reached the man’s side. I had finished medical school the year before; now my doctor instincts took over. As I got a good look at his face, I saw that he was still a boy—he couldn’t have been more than 17. There was an entry wound above his right eyebrow, and because he was lying on his side I could see a fist-size exit wound at the back of his head. My inner narrator began calling out a status report like I had been trained to do in the trauma bay: Gunshot wound to the head! No other signs of penetrating trauma!

In the movies, the guy would have been out cold, but in real life he was throwing up on himself. I’d seen a lot of scary stuff in hospitals, but this was different. Time seemed to slow down. I found myself shifting into autopilot. I kept checking things off the list that I had learned in medical school: ABCD—airway, breathing, circulation, disability. Keep his airway clear. Make sure he’s breathing. Check his pulse. Maintain the position of his cervical spine in case his neck is broken. At the same time, a voice in the back of my head kept telling me that I wasn’t in the safety of the emergency department—there was no security guard at the door, and the red car could return. Every cell in my body was telling me to get the hell out of there, but I stayed by his side until the paramedics arrived.

Hours later, as my friends and I sat in the Mission District police station giving our best descriptions of what we had seen, we got the news that he didn’t make it. It was a heartbreaking end to the evening, but I knew there was nothing else I could have done.

When I got home that night, I couldn’t sleep. In the following weeks and months, every time I saw a red car approaching quickly or heard a car backfire, I felt transported back to the fear I felt that night. I would have the same physical responses: My heart would pick up its pace, my eyes would dart around and I’d feel tightness in my stomach. Now I know that my biology was reacting to an unusually high level of stress by linking red cars with danger. My body was remembering what happened and sending a flood of stress hormones shooting through my system in case the red car now was as dangerous as the red car before. My body was doing what it was designed to—keep me out of harm’s way.

Day to day, your brain has to process a lot of information—trees creaking in the wind, dogs barking next door, the wall of air hitting your face as a subway car hurtles by—and interpret the level of risk. In order for humans to survive, the brain and body had to come up with efficient ways of processing information, and the stress-response system is one of them.

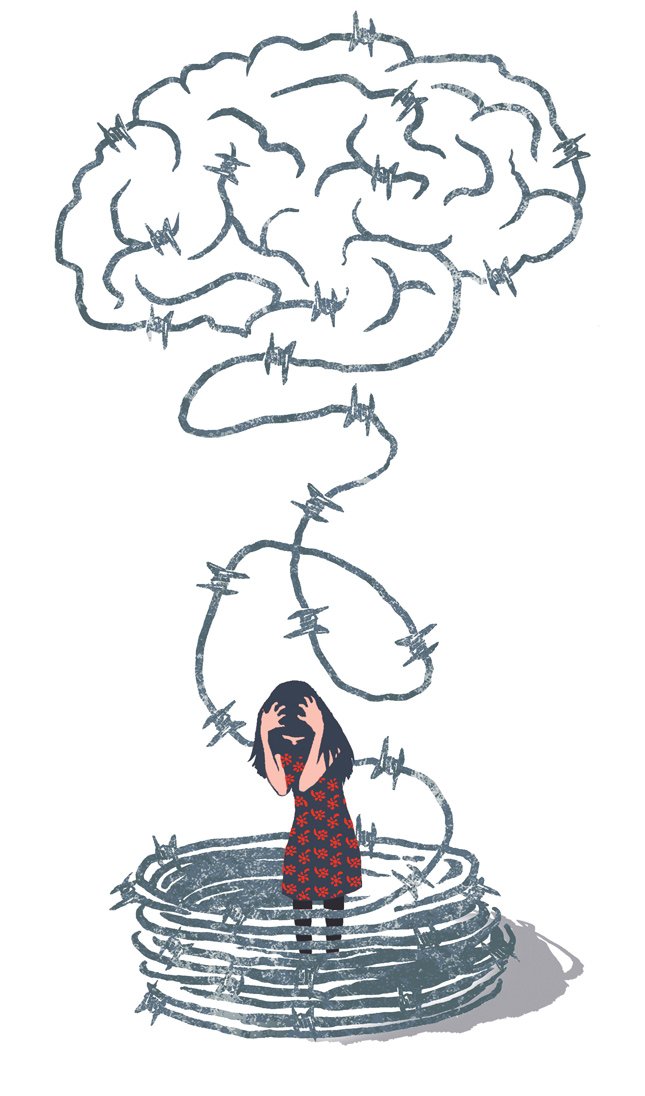

But the stress response can do its job a little too well sometimes. This happens when the response to stimuli goes from adaptive and lifesaving to maladaptive and health damaging. Almost everyone knows, for example, that soldiers sometimes come back from the front lines with post-traumatic stress disorder. That’s an extreme example of the body remembering too much; the stress response repeatedly confuses current stimuli with the past in such a dramatic way that it becomes hard for these vets to live in the present. They may hear a B-52 bomber overhead or a commercial airliner taking tourists to Hawaii, but their bodies feel the same—in mortal danger. The stress response is caught in the past, stuck on repeat.

The trigger of a red car would eventually decouple from my body’s most ancient defense mechanism. My brain would stop interpreting it as a threat. Now, when I see a red car pass me on a city street, I don’t flinch. What I didn’t know until years later was why. Why was my body able to recover from that intense instance of stress? What made the sensory connection between the red car and the biological reaction of my stress response fade?

In the months after coming across the ACE study from Kaiser and the CDC, I dived into the research. What I know now is that what happened in my body that night in the Mission District is the same thing that happens to my patients’ bodies when they experience a host of adversities ranging from abuse to abandonment. The body senses danger, and it sets off a firestorm of chemical reactions aimed to protect itself. And, most important, the body remembers.

Children are particularly sensitive to repeated stress activation. High doses of adversity affect not only the brain structure and function but also the developing immune system and hormonal systems, and even the way DNA is read and transcribed. Once the stress-response system gets wired into a dysregulated pattern, the biological effects ripple out, causing problems within individual organ systems. Because the body is like one big, intricate Swiss watch, what happens in your immune system is deeply connected to what happens in your cardiovascular system.

The elegantly designed, evolutionarily imperative stress-response system works like this: Imagine you’re walking in the forest and you see a bear. Immediately, your brain sends a bunch of signals to your adrenal glands (perched on your kidneys) saying, “Release stress hormones! Adrenaline! Cortisol!” Your heart starts to pound, your pupils dilate, your airways open up and you are ready to either fight the bear or run from the bear. That’s the response commonly known as fight or flight. It has evolved over millennia to save your life.

One not-so-obvious but incredibly important function of the stress response is activating the immune system. After all, if you are fighting a bear, he might get in a couple of licks. If he does, you want your immune system primed to heal.

Once you do get away and are back in the safety of your cave, the body uses a sort of stress thermostat called feedback inhibition that causes the stress response to disarm. High levels of adrenaline and cortisol feed back to the parts of the brain that initiate the stress response and turn them off. What an incredibly evolved system! Especially if you live in a forest and there are bears. But what happens when you can’t experience safety in your cave…because the bear is living in the cave with you?

The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity ($27, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 272 pages). For more information, visit centerforyouthwellness.org.